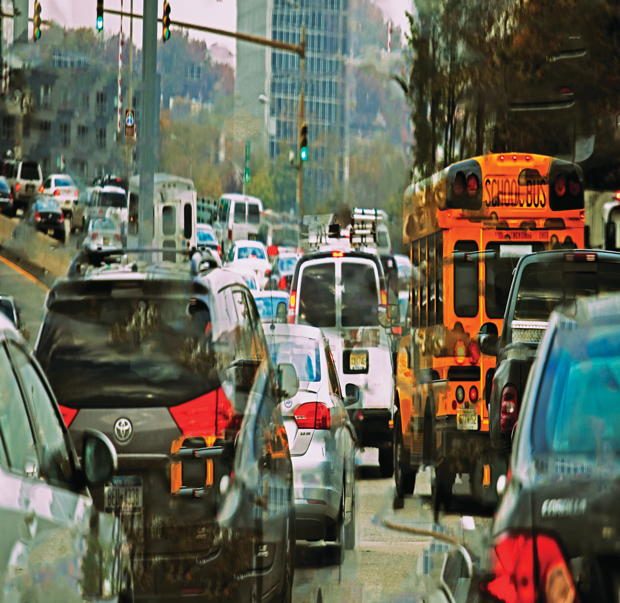

These are the roads that try drivers’ souls–the bottlenecks where the stream of brake lights glares back at you like a legion of demons’ eyes; the narrow old highways where one person’s flat tire can ruin a thousand mornings; the strip mall corridors where you sit marooned through several traffic-light cycles contemplating the existential question: Is this where I will spend eternity?

It feels like eternity, so there’s little consolation knowing that New Jersey drivers spend about an hour each week stuck in traffic. In fact, it’s what you might expect from the most congested state in the Northeast, as measured by vehicle lane miles traveled annually, says the state Department of Transportation.

How bad is our traffic? According to the most recent congestion scorecard from INRIX, the popular traffic app, the New York metropolitan area, in which New Jersey is lumped, is fifth worst in the United States, behind Honolulu, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Austin.

More than 40 percent of our roads operate either at or near capacity, a problem that vexes Dennis Motiani, the DOT’s assistant commissioner of transportation systems management and a veteran New Jersey Turnpike and Route 206 commuter.

“You can’t build any more or wider highways in New Jersey,” Motiani says. “So how do you use an existing network and still improve efficiency? That’s what we are tasked with.”

Bumper-to-bumper traffic can stress, anger and frustrate otherwise even-tempered people. It’s an intractable problem most Jerseyans have learned to live with.

Yet the DOT is clawing some victories in its battle to improve our quality of life. For North Jerseyans, the summer exodus to the Shore has been eased by the EZPass express lanes on the Garden State Parkway south of the Driscoll Bridge. Over the last 15 years, faster, more efficient management of crash sites has reduced the average time to clear an accident and reopen a lane from 2½ hours to 40 minutes, Motiani says. Coordinated traffic signals, timed so that at a given speed you can flow through a succession of green lights, have also helped. In beach season, it used to take 45 minutes to get through the 12 traffic lights along Route 72 in Stafford Township on the way to Long Beach Island, Motiani says; now it takes 15 minutes.

Still, for most of us, traffic remains a pain. To determine the state’s 20 worst traffic hot spots, New Jersey Monthly surveyed a panel of five of the area’s best-known traffic reporters. They cited a multitude of spots clogged daily by commuters crawling toward what Motiani wryly describes as “the two biggest cities in New Jersey: New York and Philadelphia.” Many other bottlenecks flummox drivers who are just trying to get around the state.

The list that follows, presented in no particular order, is based on our panelists’ picks. It pinpoints 20 locations where you are most likely to sit drumming your steering wheel in frustration. Not that there’s any shortage of other deserving candidates. For each of us, the worst route is likely the one we have to wrestle with regularly. Still, if you’re a Jersey driver, chances are you’ve found yourself in one of these pickles:

1. Garden State Parkway, between the Union and Essex tolls, was the most commonly cited spot, with the stretch between exits 142 and 145, where it intersects I-280, ranked by INRIX as the worst traffic corridor in the state and 99th worst in the nation. It is a narrow chute through city neighborhoods that border it so tightly that it has nowhere to expand. But you can comfort yourself with this thought as you inch past Holy Sepulchre cemetery, which straddles both the Parkway and the border of Newark and East Orange: You, at least, will not be here forever. Alternate route: “The Turnpike flows better, but if there’s an accident, you’ve got 6 miles to go before you have an exit and a way to get out,” says Cara Di Falco, traffic reporter for News 12 New Jersey.

2. U.S. Route 17 is so bad that it claimed two of the state’s four spots on the INRIX worst-corridor list: the narrow two-lane stretch in Rochelle Park (ranked 181st by INRIX out of approximately 219); and the dense retail mecca in Paramus, where reentering the road after shopping is a high-stakes poker game (128th). The best alternative: other than Sundays, when Bergen County’s blue laws close most of the stores, is the GSP, which parallels Route 17 between Route 3 and the New York Thruway, says Bernie Wagenblast, who has been watching traffic for more than three decades at public transportation agencies, private companies and as one of the original Shadow Traffic reporters in 1979. He publishes the Transportation Communications Newsletter and gives weekend traffic reports on 1010 WINS and New Jersey 101.5.

3. I-287 from Piscataway to Edison was built as a bypass that subsequently became a magnet for development. “This is one of those roads where, when you see brake lights, you fear a 20-mile jam, and sometimes it is,” says Matt Ward, a traffic reporter for 25 years who works for Total Traffic & Weather Network and is heard on 1010 WINS Radio and New Jersey 101.5.

4. In Camden County, the hairpin turn where I-295 connects with I-76 and NJ Route 42 has been so notorious for so long that it still carries the name of the long-defunct nightclub that once overlooked it: Al-Jo’s Curve. It is destined to be erased as part of a $900 million state construction project, Direct Connection. “We can already see dramatically improved traffic flow in the areas where the roadway has been widened, along I-76 between the Walt Whitman Bridge and the Route 42 freeway,” says Laura Tortella, also with Total Traffic & Weather Network. She reports on South Jersey traffic for WIOQ, WISX, WRFF, WDAS, WUSL and WJJZ. “To complicate matters,” she says, “there are ongoing construction projects that are impacting the commute for drivers on the Ben Franklin Bridge, the Walt Whitman Bridge and the I-76/Route 42/I-295 [complex]. With that comes the threat of intermittent lane closures throughout the day.” Crews will be working there until 2021.

5. Trucks crossing the George Washington Bridge are barred from the lower level, a security measure that has been in force since 9/11 and clogs the New Jersey approaches to the upper level. Leave the I-80/95 express lanes to the 18-wheelers and the tourists. Stick with the local lanes and the lower level.

6. If you need to take the Lincoln Tunnel at the peak of the morning rush, you can expect to spend at least 45 minutes backed up on I-495. The creeping does come with a consolation prize: Once you reach the Helix and the Manhattan skyline swings into view, you have the most majestic vista of any traffic jam in the state. “I recommend the Holland [Tunnel],” Di Falco says. “Of the crossings, that seems to back up the least.” Even more scenic: Park your car at Port Imperial in Weehawken and cross the Hudson on the ferry.

7. U.S. Route 22, built in the 1920s, was one of the original federal highways. In those days, 35 mph was cruising speed, and it seemed perfectly reasonable to fill not only the east- and westbound outer roadsides, but also the median strip in Union and Springfield, with all manner of commercial enterprises. Vehicles reenter the highway from both left and right; recurring U-turn lanes require cars and trucks to accelerate from a standstill back into the flow of traffic; signs flash and beckon from all sides; and pretty soon you feel like the silver ball in a pinball machine. “It tends to be worse on the westbound side,” Wagenblast warns.

8. Another relic of the 1920s, NJ Route 21 is similarly narrow and antiquated. It gets particularly clogged as it cuts through Newark—the stretch known as the McCarter Highway. “It’s always a mess; it’s always backed up,” says Di Falco. “But if you have to get into Newark, you’re going to have to sit on 21.” One saving grace: If you need a muffler, windshield, tire, engine or body work, even an entire used car, businesses on almost every block are at your service. Best alternative: the New Jersey Transit trains that pass on the parallel viaduct as you wait at yet another red light.

9. Heading east into Newark, I-280 divides, narrows, rises and bends after it passes under the Parkway in East Orange and approaches downtown. “It drops a lane as you’re coming into the state’s largest city,” Di Falco says incredulously. As you crawl toward the Route 21 interchange, you will have plenty of time to admire the Gothic twin towers of Sacred Heart Basilica, which may make you wonder who the patron saint of commuters is, and where prayers for relief might be directed.

10 & 11. Commuters who were lured by lower prices and larger properties to western Sussex, Warren and Morris counties (even, dare we say it, to Pennsylvania) crawl along I-80 from Wharton to Parsippany. Similarly, parallel to I-80 but about 15 miles south, commuters from Hunterdon creep along I-78 east of NJ Route 31, a tree-lined stretch of interstate that feels too distant from any population centers to produce such jams. Both 80 and 78 run three lanes in each direction through most of their rural western stretches. But that doesn’t ease the pain. “At some point, it’s going to come down to, ‘How many more lanes can you have?’” Motiani says. “Look at L.A. They have six lanes in each direction and they’re still crowded.”

12-14. South Jersey’s daily traffic jams are concentrated around the bridges that carry commuters across the Delaware River to and from Philadelphia. “You have a whole lot of people driving the same roads at the same time each day,” Tortella says. Getting over the Walt Whitman Bridge requires serious heel-cooling on what is laughably called the I-76/NJ-42 “Freeway.” Ben Franklin Bridge travelers develop an intimate acquaintance with Admiral Wilson Boulevard (U.S. Route 30) in Camden. And those who use the Tacony-Palmyra Bridge endure a daily gamble no other local commuters face: The TP is a drawbridge, and it opens often. In October 2013, it was stuck open for 11 hours, including the morning rush.

15. In the middle of the state, U.S. Route 1 is the main north-south artery through what might be called Princeton’s Aspirational Corridor, a busy stretch lined with corporate office parks, automobile dealers and restaurants from Plainsboro to North Brunswick. During rush hour, drivers lurch haltingly from one red light to the next. “Too many traffic lights and too many cars,” says Matt Ward. “There is a delay every day on this road.”

16. Barnacled with strip malls and jughandle turns, NJ Route 18 cuts through East Brunswick like a Central Jersey sibling of Route 17. Its traffic signals, though, have received the same makeover as those leading to Long Beach Island. It used to take 16 minutes to traverse the 13 lights along this stretch, according to Motiani; now you can get through in 10. “If you add these things, slowly it helps commuters,” he says. “They don’t even realize it, but five minutes here, two minutes there, it helps.”

17 & 18. Summer brings its own brand of jam. At the end of a sunny weekend, good luck making time through Seaside Heights on NJ Route 35 North before taking on the Parkway. Heading down to Cape May County? Be prepared to brake at the point where four-lane Route 55 turns into two-lane NJ Route 47. “Not only are you merging the traffic,” Wagenblast says, “but 47 itself is also a fairly dangerous road, because there’s nothing to prevent a car from crossing the dividing line and hitting someone head-on.”

19. Ranked second in New Jersey in the INRIX worst-corridor list, and 128th nationally, is a thrill ride that has been closed since April: the northbound lanes of the elevated 1932 Pulaski Skyway. Its 3.5-mile length will be more stable after what is expected to be a two-year renovation, but driving it will likely still feel like riding a roller coaster through a steel mill.

20. The most predictable backup on the southbound New Jersey Turnpike has always been where car and truck lanes merge near Interchange 8A in Middlesex County. “You’re taking all that traffic and squeezing it down into a more narrow roadway,” Wagenblast says. A $2.3 billion widening project just added three lanes both northbound and southbound, all the way to Exit 6. That should make life easier for anyone bound for the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Where you get stuck in Pennsylvania—well, that’s a story for another magazine.

Kevin Coyne almost always takes the George Washington Bridge, not the Lincoln Tunnel, when he drives from Freehold to teach at Columbia School of Journalism.

Back in 2002-2005 I lived in South River and attended school in New Brunswick. Door to door it was about 6 miles. At some points during the day I could get to school in about 15 minutes. Other times, an hour and a half. When I shared this remembrance w/a couple of people, they told me it was ridiculous – I was clearly mistaken. Only I wasn’t and am not. Anyone want to help me here? Do you remember sitting in traffic then or now and it taking forever during rush hour(s)?