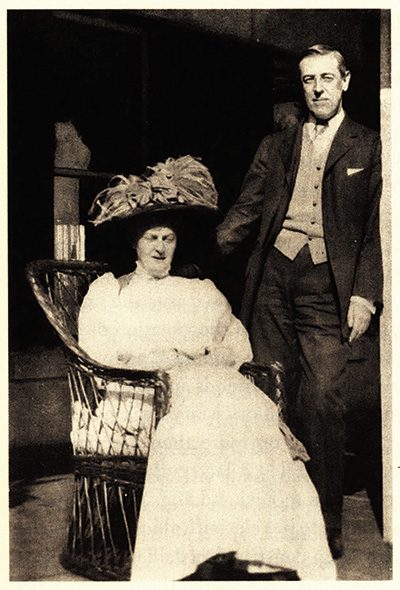

Woodrow Wilson hated having his photograph taken. His father had been handsome, but Woodrow considered himself ugly, with that curiously long jaw. Painfully uncomfortable in front of the camera, he often looked stiff, and his image as it comes down to us today is of the cold, puritanical prude. But there was nothing cold about Woodrow Wilson, the president of Princeton University who was elected governor of New Jersey 100 years ago this November—far from it.

In fact, Wilson was full of passion, ready to embrace a friend or denounce an enemy. His hot, ever-changeable nature was the result of his Scottish background, he believed. At times he could hardly restrain his temper: When a pedestrian jostled him at the Jersey City train station, Wilson nearly struck him. Struggling to control his fury, he told himself, “You can’t behave this way. You’re the president of Princeton University.”

Another time, while he was governor, a reporter snapped pictures of Wilson’s family when they were on vacation in Bermuda. Enraged, Wilson ordered him to smash the photographic plate. “Have you no instincts of gentility or gentlemanliness, whatever?” Wilson roared in full view of the goggle-eyed press. “I have got a notion to thrash you in an inch of your life.”

It was this volatile, passionate man who left academic life for politics a century ago. Wilson was elected governor of New Jersey after a controversial eight years spent at the helm of Princeton, where he had instituted radical reforms and finally run afoul of the stuffy, conservative trustees. “With his lean, long-jawed face and beak of a nose,” an observer said at the inaugural, “no one would call him handsome,” but his bold new ideas would change the state profoundly.

He spent two years in Trenton, reshaping New Jersey as dramatically as he had done Princeton. He instituted primary and election reform, corrupt-campaign-practices legislation, a public utilities statute, workmen’s comp—all benefiting the little guy. The shady political bosses who ran the state were thrown overboard by this maverick newcomer, whose fortunes were buoyed by the Progressive Movement then sweeping the country. Americans wanted change, and Wilson was consciously using the governorship as a springboard to the United States presidency.

With a swiftness rivaled in recent years by fellow Democrat Barack Obama, Wilson went from college life to the White House in just 30 months, winning the presidency in 1912. He was inaugurated a mere five semesters after he had last taught in the Princeton classroom.

Helping him all the while was his adoring Georgia-born wife, Ellen Axson Wilson. But helping him, too, was another woman, hovering in the wings—his constant pen pal, Mary Peck, a divorcée socialite he had met in Bermuda. Wilson’s utterly candid letters to Peck provide a crucial source for historians trying to understand his governorship. They also offer a tantalizing puzzle: Was she Woodrow Wilson’s lover?

The mother of three girls, Ellen Wilson was a landscape painter, a lover of romantic poetry, and a person prone to melancholy. Her father had killed himself during a bout of depression. Life weighed heavily on her, especially following the drowning death of her brother (along with his wife and infant child) when their carriage plunged off a ferry into a Georgia river as they were going to a baseball game. Then came the scurrilous attacks on her husband from his academic enemies at Princeton. When Wilson took his first vacation to Bermuda, Ellen was too worn out to come along: “I must stay with the house, like the fixtures.”

Fatefully, it was on that trip that Wilson met Mary Peck, Ellen Wilson’s polar opposite: frivolous and fashionable, a born flirt who deftly collected male admirers. Peck worked her spell on Wilson. She was amused by her catch. He dressed frumpily. He was afraid to go swimming. He left his spoon in his cup when he drank tea. Worst of all, he refused to caress her lapdog, Paget Montmorenci Vere de Vere—“I always resented this coolness,” she joked playfully.

But Peck grew fond of Wilson. Beneath his stern exterior, he was fun loving, delighting in vaudeville shows and detective novels. “I found him longing to make up as best he might for play long denied,” Peck remembered. “That, I think, is why he turned to me, who had never lost my zest for the joy of living.”

Back home, Wilson began writing dozens of letters to “my dear friend,” telling her all the things he withheld, out of compassion, from his depressed and fretful wife. As governor of New Jersey, he revealed to Peck intimate details of his political aspirations and innermost feelings. Continuing to live in Princeton, he commuted to Trenton by train, bringing piles of work home. The governorship was exhausting—“An interminable round of comment and planning and speculation and consultation and advice—the press of the whole country discussing me,” he told Mary, “and I, meanwhile, toiling on in my thought, feeling singularly lonely.”

In his formal Trenton office overlooking the Delaware River “with its uncouth banks,” office-seekers droning on, Wilson allowed his mind to wander. Now he was aboard a ship to Bermuda over the bright water, now stepping onto the narrow dock, now hurrying up the path to the villa where Mary Peck awaited him in her hammock, ready to chat through languid easy hours. “It revives me,” he told her, “only to think of you.”

Poor Ellen felt obliged to tolerate her husband’s new soulmate. She believed she had failed in her wifely duty to entertain and charm Woodrow, a man who craved emotional and social stimulation. But tolerant though she appeared, inside she seethed with resentment and hurt, as her surviving brother, Stockton Axson, could see.

During the hard-fought 1912 presidential campaign, Wilson’s political enemies scrounged for dirt. Ugly whispers vilified him as “Peck’s Bad Boy”—an allusion to a fictional nineteenth-century prankster created by author George W. Peck. “The campaign of slanders against him was almost unbelievable,” Axson remembered. Reporters knocked on doors in Princeton seeking salacious details, but even his opponents couldn’t believe that Wilson (famously high-minded and an elder of the First Presbyterian Church in town) was capable of steamy intrigues. Asked what he thought of reports that Wilson and Peck dragged blankets to a secluded Bermuda beach screened by vegetation, Princeton’s famed professor William Francis Magie quipped, “Personally, I think he read her poetry.”

The last word belonged to Teddy Roosevelt, Wilson’s opponent in the 1912 presidential election, who made the immortal pronouncement, “No evidence could ever make the American people believe that a man like Woodrow Wilson, cast so perfectly as the apothecary’s clerk, could ever play Romeo.”

Worn out by life, Ellen died in the White House in 1914. She was 54. Wilson confessed to his doctor that the friendship with Mrs. Peck—indiscreet but not improper, he called it—was the only unhappiness he had ever caused her. Within months, the President announced his engagement to Edith Galt, a wealthy widow. Fearing that this sudden and unseemly remarriage would ruin Wilson politically, his staffers undertook a desperate expedient, lying to him that Mary Peck was threatening to sell all the letters Wilson had written her. They hoped this roadblock would scuttle the wedding.

It was a cruel trick. An agonized Wilson went groveling to Edith Galt to tell her the truth about the Peck relationship: for a brief time he had written her too ardently; it was a folly that he had later rued, and Ellen had forgiven him. The relationship was not physical, he insisted. Edith believed him, and soon they were married in the White House.

Meanwhile, Mary Peck was crushed in her dream that Wilson would ask her hand in marriage. In her later years, alone and penniless in California, she told a visitor sadly that Woodrow would have proposed to her, only his handlers “wouldn’t let him.” The man she had loved was no cold, bloodless prude, she insisted, but a warm and passionate friend who had unforgettably touched her heart.

W. Barksdale Maynard is author of Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency (Yale University Press, 2008).

Woodrow and Edith Wilson were not married in the White House, in December of 1915. They were married in her Washington, DC home.