“You gotta let ’em hear ya in Jersey, man!” Bruce Springsteen coaxes a crowd of thousands at New York’s Madison Square Garden as he kicks off a rousing rendition of “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” on a summer evening in 2000.

When, halfway through the song, he introduces longtime bandmate Steven Van Zandt—“the minister of faith and friendship, keeper of all that is righteous on E Street, and star of The Sopranos television show”—the arena erupts in near-deafening applause. Van Zandt nods solemnly in gratitude, casting his eyes downward. He’s got swagger, to be sure, but at this moment, he emanates demureness above all else.

Van Zandt is set to appear in person at the Montclair Literary Festival on October 3.

For all the high-powered triumphs Van Zandt has enjoyed throughout his career—most famously as a guitarist for one of the most venerable rock ’n’ roll bands in history and as the iconic Silvio Dante on The Sopranos—an astonishing portion of his work has gone, by his own account, unheard.

He documents his lifetime of musical passion projects—often heartbreakingly dismissed, squelched, shelved or overshadowed—alongside the more commercially successful ones in his new memoir, Unrequited Infatuations: Odyssey of a Rock and Roll Consigliere (A Cautionary Tale), out now from Hachette Books.

“I didn’t want it to be a typical [auto]biography,” Van Zandt tells New Jersey Monthly. “I wanted it to read more like a detective novel of somebody trying to find their purpose in life and their justification for existence.”

***

Before joining one of the most iconic Jersey bands of all time, Van Zandt, now 70, planted roots in the Garden State at the age of 8, leaving Boston and moving with his family to Middletown. He was raised as an “extremely devout” Christian, getting baptized, attending Sunday school, and even accompanying church elders to a Highlands mountaintop for a few Easter services at dawn.

But while listening to Curtis Lee’s “Pretty Little Angel Eyes” in his bedroom at age 10, he was overcome with “a rush of exultation”—his first epiphany, he recalls in the book, of music’s transcendent power. This fascination would soon eclipse his religious fervor. “I obviously had some genetic penchant for metaphysical zealotry,” he writes. “A need to be part of something larger. A sense of wanting to belong is built into human nature; the zealotry part is what separates the holy rollers, and holy rock and rollers, from regular, far more sane civilians.”

He bought his first guitar at the still-standing Jack’s Record Shoppe in Red Bank, and met Springsteen when they were both long-haired teenagers playing in different South Jersey bands. They began taking the bus into Manhattan together to catch new music at Cafe Wha? in Greenwich Village (where Van Zandt lives today with his wife of nearly 40 years, Maureen). Back in Springsteen’s Freehold bedroom, they traded their favorite records.

After Van Zandt “reluctantly and meaninglessly” graduated from high school, he played gigs in Jersey and beyond. Springsteen introduced him to Asbury Park’s Upstage Club, above a Thom McAn shoe store, where he discovered a vibrant Shore music scene (and met future E Street Band members Garry Tallent and the late Danny Federici, who died in 2008). A shared apartment with Springsteen housed “two mattresses on the floor. Not much else,” he writes. “When there was no more room in the sink for the pile of dishes, we moved.”

***

He officially joined the E Street Band in 1975 for the Born to Run tour, not long after Springsteen had called him into the recording studio to help out with the horn arrangements on the album’s tune “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out.” (The craft of arranging, Van Zandt tells us, is still his “favorite thing of all to do.”)

Amid the band’s mainstream success, Van Zandt remained fiercely loyal, but simultaneously—and often singularly—unintimidated about challenging Springsteen if he felt it necessary.

He would later mine elements of this alliance when building his Sopranos character, Mob boss Tony Soprano’s consigliere, whom he played on HBO from 1999 to 2007. “Internally, I did end up using the dynamics of the relationship with Bruce—being the best friend, being one of the few people who are really not afraid of them, having to bring the bad news occasionally,” he says, before adding with a laugh, “having a fight and being blamed for the bad news.”

[RELATED: ‘The Many Saints of Newark’ Has New Jersey in its Veins]

In 1982, following the success of Born to Run and The River, Van Zandt found himself desiring some reciprocity for his career-long loyalty.

“I felt I’d earned an official position in the decision-making process. [Springsteen] disagreed. So I quit,” he writes.

Although Van Zandt soon regretted his decision and would later refer to it as the biggest mistake of his life, he remains grateful that the opportunity allowed him to pursue a solo career and political activism.

“I think occasionally an artist’s job is to ask themselves, How can I be useful?” he says. Taking a cue from rock ’n’ roll’s tradition of “communicating internationally about certain common-ground issues,” he recorded “Sun City,” a protest song about South African apartheid, in 1985. The project is “sort of the most successful thing I’ll ever do,” he says.

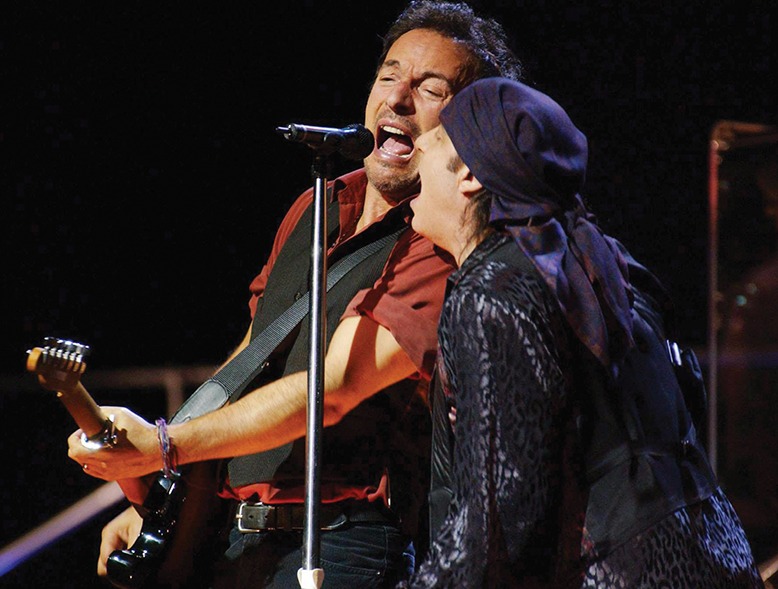

Van Zandt officially rejoined the E Street Band in 1999, years after reconciling personally with Springsteen. “I shouldn’t have left in the first place,” he writes, adding that “the band’s place in history needed to be secured.”

Bruce Springsteen (left) performs with Van Zandt on tour following the release of The Rising in 2002. PA Images/Alamy Stock Photo

Many of Van Zandt’s later career endeavors are characterized by his efforts to preserve rock ’n’ roll’s legacy. “I’ve dedicated the last 20 years of my life to trying to keep it alive,” he says. “It’s an endangered species, no doubt about it.”

He debuted Little Steven’s Underground Garage, his nationally syndicated radio show on SiriusXM, in 2003. It continues to celebrate what is now 70 years of rock, and serves as an antidote to what he decries as the homogeneity of the mainstream airwaves and music business.

“Paul McCartney puts out a new record, or Ringo [Starr], or the Rolling Stones, or Cheap Trick, or Joan Jett—I’m the only one playing it,” he says of his show. “And I’m like, Why is that? I don’t get it. They’re still making great records…. I have extremely high standards. I don’t do anybody any favors; I’m not a nice guy! You gotta be great to get on our radio network.”

Another arena Van Zandt has tackled in his mission to safeguard the arts is education.

Dismayed by stories from teachers in the early aughts that music and arts programs were dwindling amid an increased emphasis on testing, he began developing an interdisciplinary music-history curriculum called TeachRock. More than 40,000 teachers nationwide have since registered for its free lesson plans and materials, and the New Jersey School Boards Association has endorsed the program. “We need to teach our kids how to think, not what to think,” he says.

Van Zandt also remains involved with production at Wicked Cool, the record label he founded in 2005. He examines everything from composition to instrumentation to mixing, suggesting “whatever I can to realize the potential of [a] song,” he says. “It’s important to me that every song counts. I don’t believe in being casual—about anything, really.”

Despite having abandoned his Baptist religion long ago, Van Zandt refers now to his multimedia successes as “predestined,” especially because he never planned them.

“I had no intention of being an actor,” he says. “None. Never. I thought about directing, I thought about writing. But I never had a big need to be a performer, to be the front guy, whether it’s being a rock star or an actor or a politician, God forbid.”

Performing, Van Zandt explains, can be a glorious celebration, a liberating hiatus from his own head. (“Any time you’re not thinking is a vacation,” he muses.) But in his experience, performing is ultimately not as gratifying as the behind-the-scenes artistic grind.

“We all have that creativity in us, and I think we need to exercise it,” he says. “… It doesn’t [always] pay the rent, but there is some satisfaction with creating something that you feel you’ve done your best at, [when] you’ve realized your potential in that piece of work. It’s important that everybody gets a chance to do that.”