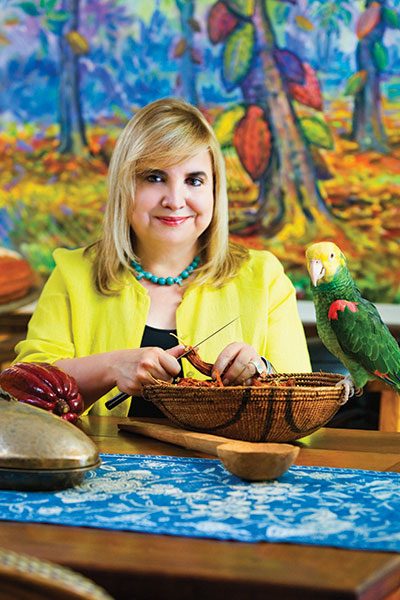

Born and raised in Cuba, Presilla earned a Ph.D. in medieval history in 1989 and became a widely-traveled expert on Latin-American cuisine and culture even before opening Cucharamama, Zafra (serving Cuban food) and Ultramarinos (a Latin food store, pastry shop and learning center). While doing all that she wrote five books—three on Latin American cultures and two on chocolate and cacao—and kept chipping away at her magnum opus, Gran Cocina Latina (W.W. Norton). Since its publication in October, this groundbreaking, 901-page cookbook packed with illuminating essays has capped her year with more acclaim.

Gran Cocina Latina was 30 years in the making. But it didn’t start out a cookbook. What was the original plan?

In my travels I collected recipes simply because I was a home cook. As a trained historian, I took meticulous notes on everything, including the stories of the cooks.

How does medieval history connect with modern Latin American cooking?

In the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance, the Spanish and Portuguese who conquered the Americas left their imprint on everything from food to language to religion to music. The desire to animate the flavors of a sauce with a sweet-and-sour accent is something the Iberian conquerors brought with them, and you see it in expanded form today in the Latin American tradition of playing sour, sweet, salty and sometimes hot and savory flavors freely against each other. But many aspects of the indigenous food cultures survive, largely involving the ingredients used, the ways they are combined and the cooking techniques employed.

How do you account for this survival?

It has to do with the way the Spaniards were. They integrated themselves at every level of society. In Peru you see see paintings of weddings between Inca women and Spanish captains. The Spanish were very promiscuous in both bed and table, more so than any other colonial force in the world. We are the result of all that. It’s not what you saw in India with the British. It didn’t happen the same way in North America. I think it is a healthier model, our model.

How did the Spaniards relate to the native foods?

If they didn’t have something they substituted. Bread is a good example. The Spanish came from a Mediterranean culture where bread was everything. In the Americas they saw these disparate cultures in which a different kind of bread is everything—flatbreads like tortillas, arepas and casabe. The Spanish understood that completely. In most regions the climate was too hot to grow wheat, so they happily ate corn tortillas and yuca bread.

Were you forced to leave anything out?

Several hundred pages had to be cut, including my travelogue, because I did not want the book to cost more than $45. Some of that is now available on the website, grancocinalatina.com.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

Diversity and unity. That’s what’s really wonderful about Latin America. Sure, there are separate strains of geography, but underlying culinary themes unite us. Take sofrito, a basic sauce. It may go by different names in different places, but the DNA is shared.

Will readers have difficulty finding ingredients?

It’s awesome that all the food pictured in the book is available within walking distance of my home in Weehawken. There was nothing I could not find.