Illustration by Viktor Koen

After New York, no state has been harder hit by the Covid-19 pandemic than New Jersey. So it’s fitting—given both our sense of urgency and our wealth of medical and scientific resources—that the state is deeply engaged in the global effort to vanquish the disease. From vast pharmaceutical and research powerhouses like Johnson & Johnson and Rutgers University to a small biotech company with a single focus, New Jersey scientists are playing an essential role in the search for ways to treat patients suffering from Covid-19 and to stop the disease in its relentless march across the globe.

The push for a vaccine

When Paul Burton, the chief global medical affairs officer of Johnson & Johnson’s Janssen pharmaceuticals division, talks about the company’s efforts to create a vaccine to protect against Covid-19, he uses words like “unprecedented” and “unparalleled.”

Under other circumstances, those adjectives might be dismissed as hyperbole, but in this case they’re merely descriptive. Never before has the search for a vaccine been so aggressive or so accelerated (which, by the way, are also adjectives Burton uses).

In the case of Covid-19, a process that can take 10–15 years is being squeezed into a span of 12–18 months. It began almost immediately after January 10, the date on which Chinese scientists announced that they’d successfully decoded the genome of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19.

Janssen was well positioned for such a challenge. It had already developed successful vaccines for Ebola and Zika, so it had in hand the technology to create new vaccine candidates.

“Creating the new vaccine,” Burton says, “involves taking a piece of the coronavirus DNA—specifically, one that codes for the protein that latches onto human cells—and placing it inside a dead adenovirus.” An adenovirus, Burton explains, is basically a safe common cold virus, which is good for transporting things into humans, but it lacks the DNA needed to replicate. “So, the vaccine”—essentially, the coronavirus DNA and the dead adenovirus that contains it, along with inert components the keep the vaccine from degrading or its ingredients from separating—“can’t cause a cold,” Burton says. “And the protein it produces can’t cause harm either.”

[RELATED: Terror, Triage & True Heroics: Meet Jersey’s Valiant First Responders]

For the hoped-for Covid-19 vaccine, Janssen found three extremely promising pieces of coronavirus DNA from which they’ve created three separate vaccines: a lead candidate and two backups. After a candidate is chosen, a series of clinical trials will start. If the vaccine is found to be safe and efficacious, manufacturing will ramp up.

What Janssen is doing—and as far as Burton knows, this has never been done before the Covid-19 pandemic rendered the need for a vaccine so urgent—is conducting various phases of vaccine development in parallel, rather than in sequence. As of this writing, the company was expecting to begin Phase 1 trials as soon as September and was already preparing for the manufacture of 300 million doses of the vaccine, which could be delivered to the public by the end of this year. “That,” says Burton, “is an unprecedented timeline.”

Also unprecedented is the amount of collaboration, both nationally and globally, on the creation of this particular vaccine. J&J researchers in New Jersey, across the country, and in Janssen’s facilities in the Netherlands are all working on the vaccine, along with scientists at BARDA—Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, a branch of the federal government with which Janssen already had a relationship—and a host of other organizations around the world.

“When we do research, we definitely do it globally,” Burton says. “What I think is unprecedented is the degree of collaboration and engagement and energy that everybody is bringing to this problem right now. It really is a team effort.”

Rutgers rallies its forces

In late March, as Covid-19 forced educational institutions across the country to shut down most of their ongoing research activities, Rutgers announced the formation of a university hub known as the Covid-19 Center for Response and Pandemic Preparedness.

Like the country’s other great research universities, Rutgers called on scientists across an array of its own institutions—including the Institute for Infectious and Inflammatory Diseases; the Institute for Translational Medicine and Science; Rutgers New Jersey Medical School; Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey; and schools of pharmacy, public health, engineering, computational science, social sciences and others—to focus on learning more about SARS-CoV-2 and to develop treatments for the disease it causes.

The cancer institute, for instance, is running a clinical trial to see whether hydroxychloroquine sulfate, a drug used to treat malaria and some autoimmune diseases—used alone or in combination with the antibiotic azithromycin—can reduce the amount of the virus (called the viral load) in patients suffering from Covid-19. In the trial, 160 patients are being divided into three groups: One is receiving hydroxychloroquine alone; a second is being given the combination medication; and a third is receiving a placebo, but will be allowed to take hydroxychloroquine after their blood samples have been taken on day six.

The two medications were shown to have some promise in reducing viral loads in a French study and have been widely touted by President Trump as a potential game-changer in the fight against Covid-19. (Update: In late May, France announced a ban on the use of hydroxychloroquine for Covid-19 patients two days after the World Health Organization halted its related trials.)

Steven Libutti, the Rutgers study’s chair and the director of the cancer institute, noted that there were some 15 studies going on across the nation that focused on different aspects of the two medications.

Dr. Steven Libutti chairs a multidisciplinary Rutgers study of antiviral medications, including hydroxychloroquine. Photo by John O’Boyle

While the Rutgers study expects to have data on viral load two weeks after the last participant has been enrolled, it will follow patients for an additional six months to see how the medications affect them over time. “Hopefully,” says Libutti, “since each of the studies is asking slightly different questions, the answers will give us better insights into whether these agents work, when might be the best time to use them, and which patients would be most likely to benefit from them.”

Dr. Sabiha Hussain is principal investigator on the Rutgers trial. Photo by Kim Sokoloff

(On April 24, the FDA cautioned against the use of hydroxychloroquine without close supervision, as serious heart rhythm problems have been observed in some patients taking the medication, with and without azithromycin. More recently, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, acknowledged that current data indicate that hydroxychloroquine is not an effective treatment for the coronavirus. Still Rutgers is pressing ahead with its study. Libutti notes that, as of late May, the Rutgers study had enrolled 75 patients, and researchers in the trial had not observed any serious cardiac issues.)

Another potential antiviral treatment, Ryanodex, or dantrolene sodium, is being studied by its manufacturer, Eagle Pharmaceuticals, in Woodcliff Lake. The drug works by restoring cells’ normal calcium levels, which can be affected by some viruses, and showed success at doing so against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro.

Rutgers is also studying the potential benefits of so-called convalescent plasma—blood plasma from patients who have survived Covid-19 and have developed antibodies against the disease. By April 28, researchers had infused 70 severely ill patients with the plasma. (A similar study is ongoing at Hackensack Meridian Health in Nutley.)

The Rutgers study isn’t being conducted as a traditional double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (in which one group of patients gets a treatment and the other is given a placebo, and neither group knows which is which), notes Mark Klapholz, chair of the department of medicine at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School and principal investigator on the trial, “because of the high need for some therapy that would help fight this disease, and also because of the limited availability of plasma.” (Potential plasma donors who have tested positive for Covid-19 can call 973-972-5474, or e-mail [email protected].)

As of this writing, at least one of Rutgers’s research studies was already making inroads against Covid-19, in terms of the way the disease is diagnosed. The study—led by Martin Blaser, director of the Center for Advanced Technology and Medicine; Jeffrey Carson, New Brunswick provost at Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences; and Reynold Panettieri, director of the Institute for Translational Medicine and Science—looked into the percentage of health-care workers who had contracted Covid-19, using both throat swabs and saliva samples as a means of diagnosis.

The saliva test was so successful at detecting Covid-19 that Rutgers immediately sought and received FDA approval, and the first saliva tests were being administered at a drive-through facility in Edison by April 15. The test is significant because it doesn’t require swabs, which have sometimes been in short supply, and is less invasive than the swab test and therefore less risky to health-care workers administering the test.

Rutgers also developed the first rapid test for the virus, with results available in 45 minutes, instead of one to five days. The test, notes David Alland, director of the Center for Emerging Pathogens and the new Covid-19 hub, and principal investigator on the health-worker study, has the potential to be used in clinics and doctors’ offices rather than being confined to a central lab.

In an interview posted on the university’s website, Alland said the test “will be a game-changer for crucial medical decisions, including how to triage patients, when to isolate, and how to treat.”

What’s more, because the test can identify very low levels of the virus, it could also be invaluable in helping to detect small new outbreaks of the disease once the pandemic has passed.

The university is also looking at the nature of the virus itself, particularly at the biomarkers—abnormalities in patients that indicate the presence of a disease—it elicits.

“This disease is unlike anything any of us have seen before,” says Klapholz. The markers for inflammation, for instance, have been “extraordinarily abnormal, extraordinarily high in many, many patients,” he notes. Researchers hope that studying these biomarkers will help them predict the course of the disease in patients and determine, at an early stage, who might develop a more severe form of the illness.

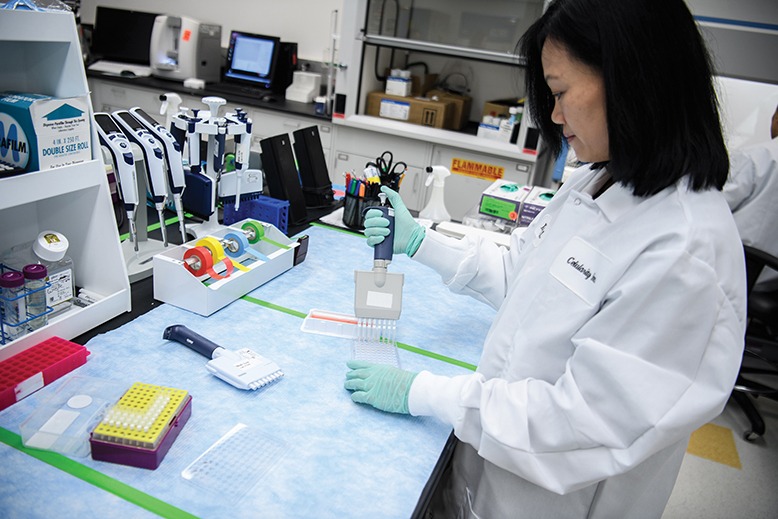

At Celularity, Robert Hariri’s team is experimenting with cell therapy to boost immune response in Covid-19 patients. Courtesy of Celularity

Boosting immunity

Work on the virus isn’t limited to pharmaceutical giants and large research universities. Celularity, a 20-year-old, Warren-based biotechnology company with some 200 employees, specializes in therapies for cancer and other diseases using so-called natural killer (NK) cells taken from human placentas. In early April, the FDA granted the company permission to begin an 84-patient trial of an immunotherapy called CYNK-001, which uses placenta-derived NK cells to help rev up the immune system in Covid-19 patients.

In the human body, NK cells are the advance guard, scouting out and destroying virally infected cells even before the immune system can begin creating antibodies against the virus causing the infection.

“This is a numbers game,” says Celularity founder and CEO Robert Hariri, “keeping the overall burden of virus low over a period of several days, at which time the patient’s own adaptive system learns how to respond to the infection.”

Boosting the immune response may prove crucial in treating Covid-19. There is some evidence that the vulnerability of older patients and those with an underlying disease is linked to a less robust immune system. It’s also possible, says Hariri, that, like HIV, SARS-CoV-2 may have the ability to damage a patient’s immune response.

Xiaokui Zhang is Celularity’s chief scientific officer. Courtesy of Celularity

The initial study, which began in April, is looking at the safety and efficacy of the drug in patients with early signs of the disease. The next wave of studies will determine whether CYNK-001 can help patients with more advanced and severe forms of Covid-19.

Some scientists have expressed worry that any drug that boosts the immune system could release a so-called cytokine storm, an immune response so extreme that it damages a patient’s lungs, heart and other organs. It’s believed to have occurred in some patients, especially those under 50, suffering from Covid-19. Hariri argues that a benefit of cell therapy is that “we can dial up and dial down the therapy by controlling the dose, the frequency or the interval of dosing, and the duration that those cells are active in the patient.”

“It’s a complicated disease,” Hariri says of Covid-19, “and it’s a complicated trial—no two patients are the same. Some are going to come in with a lot of comorbid conditions; others will come in otherwise healthy.” Even if some patients respond well to cell therapy, others may not—which is why every bit of research is so important.

Hariri no doubt speaks for all the scientists laboring to attack the world’s worst pandemic in 100 years: “This is a disease,” he says, “that’s going to require a multitude of strategies.”