On the modern industrial landscape of New Jersey, the nation’s most densely populated state, giant container cranes loom like dinosaurs over the coastal skyline near Newark. Millions of years ago that same coastal plain was home to real dinosaurs whose remains made New Jersey a hotbed of dinosaur discovery in the late 19th century.

Following last summer’s release of the summer blockbuster Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom, New Jersey’s legacy in the fossil record is rife for reexamination.

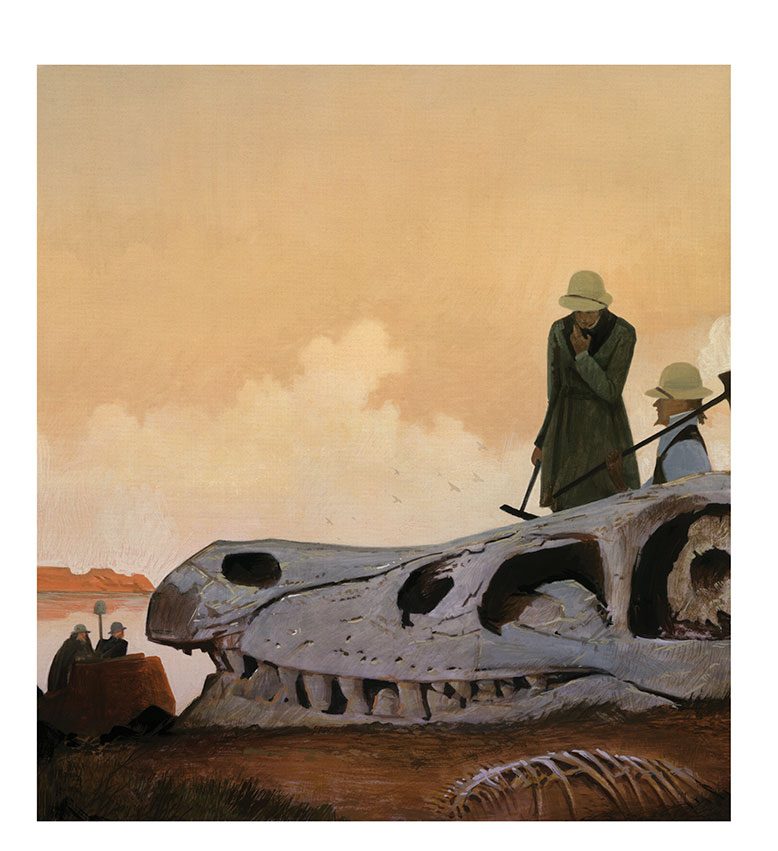

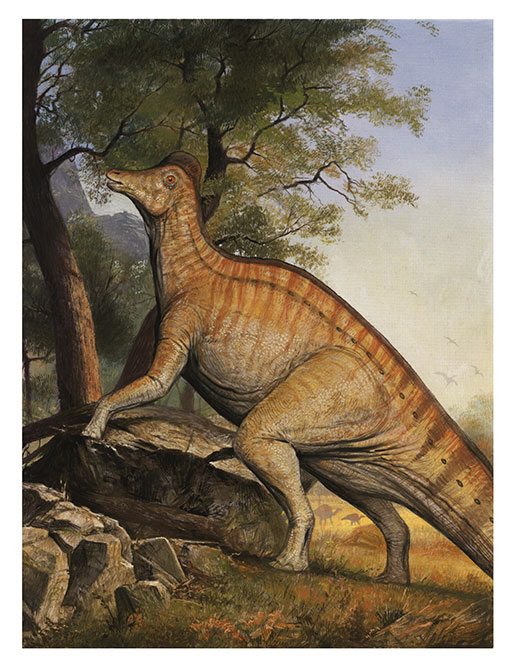

The most famous among New Jersey’s fossils is Hadrosaurus foulkii, officially named the state dinosaur by the Legislature and governor in 1991. Hadrosaurs were duck-billed, plant-eating creatures, which, like many modern-day residents of New Jersey, gravitated to the seashore. In 1838, a farmer named John E. Hopkins found strange fossils while digging marl, a mudstone used to condition soil, on his farm in Haddonfield. Not recognizing that he had stumbled upon an 80-million-year-old Hadrosaurus, Hopkins gave away some of the bones to curious friends. Twenty years later, in 1858, William Parker Foulke, a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences (now the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel) in Philadelphia, heard rumors of the fossils. With permission from Hopkins, Foulke and his team dug below and around the farmer’s original excavation. The skeleton they retrieved was like no other Foulke had ever seen.

Foulke delicately transported the remains to the Academy of Natural Sciences, where they remain today. After months of restoration, a cast skeleton was pieced together. The reptile, measuring 25 feet from head to tail, was the world’s first mounted dinosaur. The restoration team positioned it upright like a biped because of its oddly short forelimbs compared with its large hind legs. While Hadrosaurus foulkii could probably stand on its powerful hind legs like a kangaroo, some scientists, 19th century and now, theorize it was more likely a quadruped, though its locomotion is still debated in dinosaur circles.

While Hadrosaurus was the most complete dinosaur skeleton at the time, the skull was never found. Relying on a portion of the lower jaw and a few teeth, Benjamin Hawkins, an English artist contracted to cast the mount, guessed at the shape of the skull. Foulke’s Hadrosaurus is the only skeleton of its species ever found, but scientists studying skeletons of other members of the Hadrosaurids family believe Hawkins overestimated the width of the skull. Museum budgets being what they are, the Academy of Natural Sciences is unlikely to dole out funds to create a narrower skull.

Adding to New Jersey’s dinosaur trove, a nearly complete skeleton of Dryptosaurus, a meat-eating Tyrannosaur, was dug up 12 miles south of Camden in 1866. “For about 20 years, most American dinosaurs came from New Jersey,” says David Parris, curator of natural history at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton.

Hadrosaurus foulkii. Illustration by Bill Mayer

The discovery of Hadrosaurus foulkii and Dryptosaurus started a craze of fossil hunting that put New Jersey at the forefront of a burgeoning 19th-century paleontological gold rush. Recreational paleontologists sprang up across the state, and universities began forming geology departments. At the time of the discoveries, Princeton University employed only one geologist, Arnold Guyot, but by 1874 the university had attracted additional faculty and established a museum in Nassau Hall displaying the world’s second mounted dinosaur, a replica cast of Foulke’s Hadrosaurus. Two of the recruits were William Scott and Henry Osborn, close friends and members of the Princeton class of 1877. In their lifetimes, the pair would help revolutionize the field of vertebrate paleontology and popularize dinosaurs for a wide audience.

Nationwide, the race to find the biggest and most pristine fossils stoked competition as dinosaur skeletons became sought-after jewels in the crown of universities and natural history museums. Scott and Osborn joined the field team of Edward Drinker Cope, a self-taught paleontologist and member of the Academy of Natural Sciences. Their main competitor was Othniel C. Marsh, a chair of paleontology at Yale, who persuaded his philanthropist uncle, George Peabody, to fund a new museum on campus. As one of the original curators and trustee of Yale’s newly established Peabody Museum of Natural History, Marsh led expeditions to the American West to collect specimens. Cope, Scott and Osborn followed, and a rivalry that became known as the “Bone Wars” ensued.

Amid this explosion of discoveries some teams, in a race to publish first, gave different names to the same species, jumbling the fossil record. Their degradation of the scientific process didn’t stop there. These bone warriors often resorted to bribery of landowners and railroad workers, and theft or destruction of each other’s bones and dig sites. In the most sinister case, men working for Marsh planted an assortment of fossilized bones from different species intending Cope to find them and mistake them for a new species, allowing Marsh to discredit Cope. The ploy worked. Cope described the mishmash of bones as a new species. The deception was discovered only after the paper’s publication.

Despite the questionable collection methods and ethics, Scott and Osborn gathered hundreds of fossil specimens for Princeton University. Osborn became curator of vertebrate paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, in New York City. There he amassed one of the finest fossil collection in the world and assembled a team of crackerjack field researchers, including swashbuckling paleontologist Roy Chapman Andrews, who online fan pages assert was the prototype for fictional daredevil archeologist Indiana Jones. Perhaps Osborn’s connection to Princeton is the reason Indiana Jones’s childhood is set in that university town.

Diplurus. Illustration by Bill Mayer

In 1985, a century after the Bone Wars—in a twist that would have irked Scott, Osborn and Cope—25,000 specimens, the majority of Princeton’s vertebrate paleontology collection, were donated to Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History to free storage space at Princeton.

Though dinosaurs hold star-power among fossils, they make up only a small portion of New Jersey’s fossil record. Stromatolites, the remains of photosynthesizing bacteria that formed dome-like structures 1.2 billion years ago in Precambrian seas, have been found in the New Jersey Highlands. Icarosaurus, a four-inch winged-lizard, an analog to modern Draco lizards, inhabited the New Jersey landscape 228 million years ago during the Triassic Period. Like the mythological Icarus, the Icarosaurus couldn’t really fly but glided on leathery wings. The only Icarosaurus fossil was found in 1960 by a teenager meandering through a quarry near North Bergen. The fossil sold at auction for $167,000 and is now at home in the American Museum of Natural History.

A fairly common quarry fossil in New Jersey is Diplurus, a lobe-finned fish related to modern coelacanths. Diplurus fossils are found in the Triassic Lockatong Formation sandstone. Hundreds of them were unearthed in 1946 in the excavation for Princeton University’s Firestone Library.

The Ice Age also scattered bones and fossils on the New Jersey landscape. The Laurentide Ice Sheet, 25,000 years ago, was the last glacial lobe to overspread the northern tier of the state. American mastodon skeletons have been dug from deposits near recessional moraines in Sussex County.

Icarosaurus. Illustration by Bill Mayer

Though dinosaurs are extinct, interest in them and other fossils is very much alive in New Jersey. The New Jersey Expo Center in Edison annually hosts one of the largest mineral, gem, fossil and jewelry shows in the nation, drawing as many as 16,000 visitors. And, every year, Rowan University opens its fossil-rich quarry behind a Lowe’s home improvement store in Mantua Township for a community fossil dig. Fifteen hundred people, mostly families with kids, become fossil hunters for the day.

Amateurs aren’t the only ones digging. A team of paleontologists from the American Museum of Natural History is currently searching for cephalopods in ancient seabed deposits along the Manasquan River. To date, their discoveries of elevated iridium—an element rare on earth but more abundant in asteroids—in 66 million-year-old rock stratum support the theory that asteroid impact wiped out 75 percent of life on Earth, including dinosaurs.

In early May, the New Jersey State Museum, in Trenton, opened an exhibition called “Written in the Rocks,” featuring fossil stories reaching 3.5 billion years into New Jersey’s geologic past. What’s more, the museum unveiled two new life-size fossil dinosaur casts—a 50-foot skeleton of a marine reptile called Mosasaurus maximus that was collected in southern New Jersey, and a cast of Foulke’s original Hadrosaurus skeleton.

The American Museum of Natural History’s daring paleontologist Roy Chapman Andrews rode a camel while crossing the Gobi Desert in search of dinosaurs and other fossils. He could have saved himself the trouble by simply hopping a train south and getting off in New Jersey.

Perrin Hagge is a junior majoring in geosciences at Princeton University. He grew up in Wisconsin.