He graduated as valedictorian, but had initially been barred from living on the Rutgers campus because he was black. He was twice an All-American, but was benched at a game against a Southern team because he was black. He was one of the strongest voices in the college glee club, but couldn’t tour with them because he was black. He was a lawyer whose employers made it clear he would never advance in his field because he was black. He was an international activist for human rights whose passport was taken away. He was among the greatest performers of his day, but was prevented from performing at the height of his career. Paul Robeson was arguably the greatest Renaissance man of the last century, but his legacy has been virtually erased from American history.

This year, which marks the centenary of Robeson’s graduation from Rutgers, the university is working to restore Robeson’s rightful place in history with a series of forums, conferences, musical performances, dramatic presentations, lectures, commissioned portraits and the unveiling of Paul Robeson Plaza, a monument celebrating the achievements of Rutgers’s most accomplished graduate on ground he almost certainly once walked. The plaza’s construction—a gift from the class of 1971 Milestone Campaign Committee, led by alumnus Jim Savage, with ample assistance from the Rutgers African-American Alumni Alliance (RAAA)—prompted what executive vice chancellor Felicia McGinty describes as “an opportunity to uncover Robeson’s legacy and share it with the world.”

“He graced our campus under the most hostile and isolating conditions,” notes Kendall Hall, RAAA president, “yet he excelled.”

Indeed, given the obstacles Robeson faced, his achievements are all the more extraordinary. The son of a runaway slave, he was born in Princeton in 1898 and grew up in Westfield and then Somerville, where he excelled in the town’s public schools and won a full scholarship to Rutgers. He was only the third African-American to attend the university and the first to play football there. Though he endured physical abuse at the hands of his teammates, he was elected twice to the honorary College Football All-America Team. (He later played professionally for two seasons.) A gifted athlete, he was also a college standout in baseball, basketball, and track and field, earning more than a dozen varsity letters.

Robeson was also a scholar, known, even in his undergraduate days, as a powerful debater and orator, elected to both Phi Beta Kappa and Cap and Skull, Rutgers’s elite honor society. After graduating, Robeson earned his law degree at Columbia University and worked briefly for a New York law firm, but quit when a white secretary refused to take dictation from him.

The term Renaissance man is often overused, but for Robeson, it is apt. “He was an actor, singer, athlete, ethnomusicologist, an anti-fascist, anti-racist, anti-militarist political activist who risked his life participating as a performer at the front lines during the Spanish Civil War,” says Norman Markowitz, an associate professor of history at Rutgers.

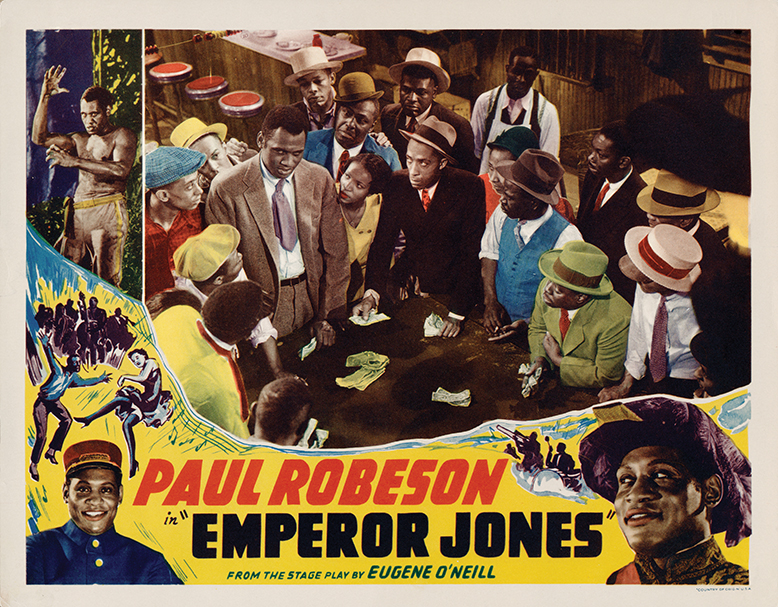

In his 1933 film debut in Emperor Jones, Robeson, as title character Brutus Jones, transforms himself from railroad porter to chain-gang convict to despotic ruler of a Caribbean island. Photo courtesy of John D. Kisch/Separate Cinema Archive/Getty Images

Thanks to television and video, Robeson is probably best remembered as a performer, particularly for his stirring bass-baritone rendition of “Ol’ Man River” in the 1928 London stage production and the 1936 film adaptation of the musical Show Boat. He is also acclaimed for the title role in Othello in a Broadway production that ran from October 1943 through June 1944. Notably, he was the first African-American in the 20th century to play Shakespeare’s most famous black character. But it was his trailblazing as an activist that would kindle a deliberate campaign to render him, in Markowitz’s words, “an unperson.”

“He paid that price,” says Edward Ramsamy, chair of Africana Studies at Rutgers-New Brunswick, “because, to some extent, he was ahead of his times in calling for the sort of transformations that those in power were not willing to accede to.” In the 1940s, he met with then President Harry Truman to lobby for anti-lynching legislation. According to Markowitz, Truman suggested Robeson leave issues like lynching to the governments of the United States and Britain, which, he claimed, had the best interests of black citizens at heart. Robeson responded with the observation that the British Empire at the time was denying freedom to hundreds of millions of dark-skinned people in its Indian colony. At that, Truman walked out of the meeting. (An anti-lynching law finally passed the U.S. Senate in 2018 but has yet to be voted on in the House.)

Robeson was also ahead of his time in viewing the nascent U.S. civil rights movement as part of a global struggle—a struggle that involved not just black men and women but all those who were fighting for the right to a fair wage and an equal place in society. In 1929, he was living and performing in London when, after a matinee performance of Show Boat, he encountered a group of protesting Welsh mine workers who had been blacklisted by their employers following a general strike in 1926. He joined the protest on the spot and, according to biographer Jeff Sparrow, continued to support the mine workers for many years to come.

He was also chairman of the Council on African Affairs, an organization formed to fight colonialism in Africa and racism in the United States. He visited the Soviet Union for the first time in 1934 and claimed it was the only place he’d ever been treated as simply a man rather than a man of color. He embraced Communism because, says Ramsamy, “of the promises it made, at least on paper, for a more equitable society”—at a time when America wasn’t effectively living up to the promises it had made in the 14th and 15th amendments, which afforded equal protection under the law and extended the right to vote to black men, respectively.

In the Cold War era, when Senator Joseph McCarthy wielded the House Un-American Activities Committee as a cudgel against prominent men and women who’d even flirted with socialism, Robeson’s unrepentant Communism earned him the enmity of those in power. The State Department rescinded his passport, and the FBI pressured concert venues not to allow him to perform, effectively destroying his ability to earn a living. He was stricken from the list of college All-Americans. When Rutgers awarded Robeson an honorary masters degree in 1971, says Markowitz, “it was done quietly, within offices, and with no ceremony of any kind.” (The federal government honored Robeson with a postage stamp in 2004.)

Before the opening of Paul Robeson Plaza, you would have been unlikely to find many students at Rutgers who knew anything at all about Robeson. Raheem Nugent, a Jamaican-American graduate student who works at the university’s Paul Robeson Cultural Center, says that, growing up in Brooklyn, he’d known nothing about Robeson except that a local high school (now closed) had been named after him. Bernice Venable, a Rutgers alumna and member emerita of the Rutgers University Board of Overseers, says that, “as a kid growing up in Somerville, I’d never heard anything about Robeson, even though I’d come from the very streets he’d walked on.”

Venable says she has a dream that, “henceforth we will not have a young man or lady saying, ‘I don’t know who Paul Robeson is.’” Still, Venable acknowledges the troubling aspects of Robeson’s biography alongside his achievements. In February, for example, the Washington Post published an opinion piece criticizing Rutgers for skirting the issue of Robeson’s support of Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. In fact, says McGinty, criticism of Robeson as a Stalinist has become “a familiar trope,” and it’s something the university plans to address in a variety of ways in the year and beyond.

“I welcome the conversation because this is an educational institution,” says Venable, “and this is what we do.”

If it’s essential to acknowledge Robeson’s support for Stalin, it’s also necessary to celebrate the supporting role he played in American history. “To some extent,” says Ramsamy, “he was the architect of the modern civil rights movement, laying the intellectual and political foundations of that movement in the 1940s.”

For Raheem Nugent, Robeson laid a path that led directly to his own experience at Rutgers in 2019. “I think about how, as a black man 100 years ago, he did the unthinkable,” Nugent says, “and it makes me think that maybe I can do the unthinkable, too.”