Travel west on Interstate 80 and you’ll see a sign as you approach Exit 19 that says “Allamuchy, 1 mile.” If you’re not familiar with these parts, you might ask, “What’s Allamuchy?” Turns out Allamuchy is a Native American word for the township bearing that name in a corner of rural Warren County abutting Sussex County. It means “place among the hills.” Makes sense: there are many hills about.

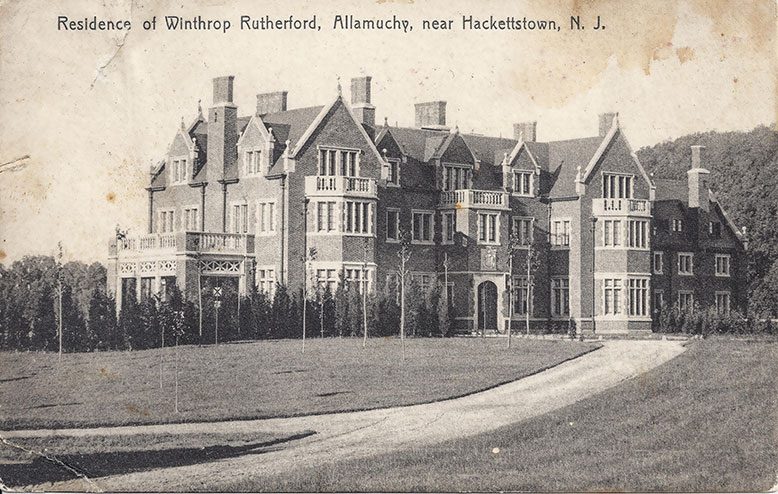

Make a left at the exit and you’ll immediately come across an historical sign for Rutherfurd Hall. Just ahead is an imposing Tudor revival brick-and-stone mansion of 38 rooms, with abundant and elegant landscaping. Think Downton Abbey.

Winthrop Rutherfurd, upon his marriage to Alice Morton, daughter of Levi P. Morton, vice president under Benjamin Harrison, commissioned the mansion. When finished in 1905, the home was a stellar example of the American Country House Movement, embraced by the wealthy in what Mark Twain called “the Gilded Age.” Its architect, Whitney Warren, was the creator of Grand Central Station in Manhattan. Its grounds were the inspiration of the Olmsted brothers, sons of Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed New York’s Central Park.

The interior of Rutherfurd Hall is magnificent, including a great open fireplace in what was once the grand living room, with the Rutherfurd and Morton families’ coats of arms carved into the stone. There’s an elegant oak staircase, with finials carved to resemble thistles (evoking the Rutherfurd family’s Scottish origins) and ceiling strapwork known as quatrefoil, depicting rustic Tudor gardens.

In its day, Rutherfurd Hall attracted many prominent visitors, the most famous being President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. On September 1, 1944, a steam-powered train chugged along the little used tracks of the Lehigh and Hudson Railroad, stopping at Allamuchy. The president, en route to his home in Hyde Park, New York, had ordered his train diverted without offering explanation to his staff and the journalists aboard. Nor did he provide any explanation when he was placed in his automobile and, using its hand controls (FDR contracted polio in 1921), drove the short distance to Rutherfurd Hall. He remained there for several hours.

Life magazine would reveal in a cover story of its September 2, 1966, issue titled “F.D.R.’s Secret Romance” that the president had gone to visit the woman he considered “the love of his life,” Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd. Several books and a novel have followed.

In 1913, in Washington, D.C., Eleanor Roosevelt had hired Lucy Mercer, 21 at the time, as her social secretary. Lucy worked for her until 1917 when, upon enlisting in the Navy (America had just entered World War I), she served as an aide to Franklin Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the Navy. In 1918, Eleanor discovered a packet of love letters in Franklin’s suitcase on his return from an overseas trip. Eleanor considered divorce, but that would have meant the end of Franklin’s political ambitions.

Eleanor made two demands: Franklin would thenceforth accept banishment from the marital bed; and he would never again see or communicate with Lucy Mercer. The first demand seems to have been met. The last of Franklin and Eleanor’s children was born in 1916, and when husband and wife were in Hyde Park she would often reside, except for official functions, in Val-Kill Cottage, two miles east of the Roosevelt family mansion.

Despite his second promise, Franklin would remain in secret contact with Lucy Mercer the rest of his life. While it is difficult to discern the level of intimacy between them, a number of letters to Lucy from Franklin have been discovered addressed to “Darling.” In 1945, Lucy, a recent widow, was with Franklin in Warm Springs, Georgia, where Roosevelt often underwent hydrotherapy on his paralyzed legs. A friend of Lucy’s was painting the president’s never-finished portrait in his cottage, with Lucy present, when Franklin suffered a fatal stroke on April 12.

Lucy died just three years later, in 1948. Many years before she had married Winthrop Rutherfurd, by then a widower, having earlier served as nanny to his six children. Lucy had converted to Catholicism, and Rutherfurd Hall was, in effect, donated in 1950 (the price was $10) to the Daughters of Divine Charity as a retirement home for nuns. They renamed it Villa Madonna and attached an infirmary building. Eventually, the number of nuns had so declined that they gave up the property. Had they sold it to developers, Rutherfurd Hall would be no more, but this was precluded by New Jersey’s Highlands Act. Instead, bonds were issued and Allamuchy Township’s school board, aided by a grant from New Jersey’s Green Acres Law, purchased it in 2007. Today, the infirmary building is an elementary school and Rutherfurd Hall, a cultural center and museum.

The museum concerns itself with other families besides the Rutherfurds with whom, over the centuries, they interwed. One such family was the Stuyvesants who built a country home a short distance away. It burned down in 1959. They were descendants of Peter Stuyvesant, the Dutch governor of New Amsterdam. The Rutherfurds also intermarried with the Morris family, which produced Lewis Morris, the first native-born colonial governor. The extended Rutherfurd family once held some 5,000 acres in Warren and Sussex counties. Now much of that land constitutes Allamuchy State Park.

Some of the remaining acres belonging to Rutherfurd Hall are located across Route 80, whose traffic unwittingly bisects the property. Nevertheless, locals contend that the curve in Interstate 80 at this point was made so as to spare the Rutherfurd family’s fieldstone chapel, once reachable on foot from the mansion.

The chapel was still being used by the Rutherfurds for family occasions into the 1960s and 1970s, but is now all but abandoned in the woods that have crept up around it. In 1969, Jacqueline Kennedy attended a baptism in the chapel of a child born to her half sister, Janet Auchincloss, who had joined the Rutherfurd family by marrying Lewis Rutherfurd in 1966.

Earlier, in 1962, Kennedy had an entirely different connection with the Rutherfurd family. As First Lady, she was determined to bring the White House up to the standard of beauty it merited. The Rutherfurds contributed some splendid examples of Duncan Phyfe furniture that came from Rutherfurd Hall. Included were two settees, two armchairs, and four sidechairs that were placed in the ground-floor library of the White House. The White House Curator’s Office confirms that the furnishings are all still there.

A stone house, dating to the 1780s and close to the chapel may also have been spared by the curve in Route 80. Rutherfurd family members occasionally stay in that house when they are in the area.

The remains of the Allamuchy train station is also north of Route 80. The station and Rutherfurd Hall are on both the state and national registers of historic places.

Finally, Tranquility Cemetery, the burial ground for the extended Rutherfurd family—Lucy Mercer Rutherfurd among them—is also north of Route 80.

Elsewhere, the Rutherfurds almost certainly inspired the name of the Bergen County borough of Rutherford, much of which was once owned and farmed by John Rutherfurd, an early settler of Scottish origin (hence the “u” instead of the “o” in the name). John Rutherfurd married into the Morris family and eventually was elected a United States senator. The generally accepted belief in Allamuchy Township, and in Rutherford itself, is that the difference between the spelling of Rutherfurd and Rutherford was due to a clerical error. Others contend that the “ford” spelling may have been in recognition of the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes, elected in 1876.

Whatever the truth of this matter, there is no question that Rutherfurd Hall is one of New Jersey’s treasures. Would that more great houses had not, over the years, been torn down to be replaced by suburban developments. Rutherfurd Hall is a shining example of how we can, and should, more zealously safeguard our heritage.

Michael Aaron Rockland is professor of American Studies at Rutgers University and author of many books. He is currently working on a new edition of his book on the George Washington Bridge.