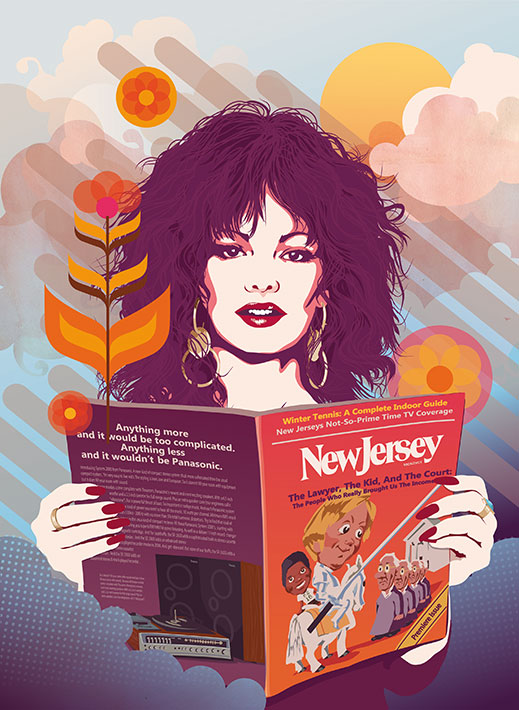

Our first issue in November 1976. Illustration: Carol Del Angel

Hendrix Niemann and Christopher Leach had a dream—and a mission.

Niemann, who grew up in northern Virginia, and Leach, from North Carolina, were roommates at Princeton. They had gone to school together at Choate, the Connecticut prep school, where they ran the weekly student newspaper. Bitten by the journalism bug, they dreamed of starting and running their own publication.

The year was 1974. Six years earlier, Clay Felker and Milton Glaser had started New York magazine as a brash competitor to the New Yorker. Its success opened the floodgates for a new publishing category: the city and regional magazine. Niemann and Leach sniffed opportunity.

Niemann recalls the moment. “Chris and I had always thought it was ridiculous that New Jersey—at the time the eighth most populous state in the country—did not have its own TV stations, did not have a newspaper with the reputation of the New York Times or the Philadelphia Inquirer, did not have a magazine. We felt the coverage, both broadcast and print, of New Jersey tended to be overly negative and stereotypical. You know, the Mafia and the Turnpike and Exit 13 in Elizabeth, which of course millions of people have smelled as they went through the state. It was a distorted picture, and there really wasn’t any respected media organ that was combating that.”

So this was their mission, however naive: “We were going to fix that single-handedly and fulfill our dream at the same time,” says Niemann. “That’s kind of how it all came about.”

What came about was New Jersey Monthly, launched in November 1976 and this year celebrating its 40th anniversary.

To start on their quest, Niemann and Leach recruited two other Princeton graduates as partners, Mike Mims, who would handle advertising sales, and Ned Scudder, who would oversee circulation. Niemann borrowed $10,000 from his grandfather, and Scudder kicked in $10,000 from his dad. First National Bank of Princeton came through with $25,000 “on a handshake,” says Niemann. “Those kinds of things still happened back in the 1970s.”

Needing more capital, Niemann and Leach “pounded the pavement” with their business plan, looking for additional investors. Serendipitously, they learned of a group of New Jersey newpaper publishers with a similar startup in mind. In a matter of months, a limited partnership agreement was signed between Niemann and Leach and the publishers of the Hackensack Record, Morristown Daily Record, New Brunswick Home News and the Burlington County Times, as well as Orange Mountain Communications, owner of WVNJ radio.

Each of the five limited partners committed $100,000, to be invested over a period of years. The initial infusion funded a prepublication subscription mailing. The response—9 percent of recipients signed on—far exceeded expectations based on industry norms. It was clear that Niemann and Leach were onto something.

Niemann and Leach rented office space at 234 Nassau Street in Princeton, one flight above Varsity Liquors. They outfitted the office with used furniture—”pretty much desks and typewriters and, back then, ashtrays,” recalls Niemann. Leach served as publisher and Niemann as editor. They were both 25. Jane Amsterdam, also 25, was recruited from Connecticut magazine as managing editor. Teresa Carpenter, fresh out of the prestigious journalism school at the University of Missouri, was named senior editor. The first masthead would include 12 regional correspondents, two Washington correspondents, and a director of research, Jason R. Golden—who, it turns out, was Amsterdam’s golden retriever.

The first issue was three months in the making. “It went on forever,” says Niemann. But the product was good. The 88-page inaugural issue—cover price, $1—opened with full-page ads for Forsgate Country Club, Midlantic Bank and all 17 locations of Bamberger’s department store. Inside were stories on the lack of coverage of New Jersey by the neighboring metropolitan TV stations; the challengers in that month’s congressional elections; a guide to indoor tennis; and tips on where to buy a farm-fresh turkey. Among the writers was political columnist Fletcher Knebel, a Princeton resident and esteemed co-author of the best-selling thriller Seven Days in May.

The 8,000-word cover story—with its unwieldly title, “The Lawyer, the Kid, and the Court: The People Who Really Brought Us the Income Tax”—delved into a now-obscure 1970 lawsuit brought on behalf of a Jersey City sixth-grader named Kenneth Robinson. The suit argued successfully that Robinson could not get an education on par with his suburban contemporaries because his city lacked a sufficient tax base. The case forced the state Legislature to impose an income tax to help fund public schools—and spawned another suit, Abbott v. Burke, which led to a series of state Supreme Court rulings that would reshape education funding in the state. Forty years later, the issue is still hot; in June, Governor Chris Christie called for a new school funding plan that defies the Abbott decision.

Putting out the magazine was hard work, but the team was having a blast. “Every day was happy hour after work,” says Niemann. “Everybody was young. I think I may have been the only one married at the time. It was just like what today would be a tech startup. Everybody in their 20s and having a good time.”

From the start, New Jersey Monthly was edgy, daring and political. It dealt with weighty issues, but also with the simple pleasures of life in our fair state. The pages were dense with text; the tone was often sarcastic. “In the early days, it had a sort of wicked humor,” Amsterdam said in a 10th-anniversary story. In the fourth issue, the magazine ran a cover story on “middle-class cheats” who collected unemployment checks while enjoying ski trips and other indulgences. Two months later, the cover snarkily (but incorrectly) projected the defeat of Brendan Byrne as he sought a second term as governor. In March 1978, a lengthy piece trumpeted the seamy details of a teenage sex ring in Sussex County. That May, Carpenter revealed the “hate-filled world” of Jersey’s Ku Klux Klan.

Early in 1978, Amsterdam left the magazine and was replaced by Michael Aron, a Philadelphia native who had previously served as associate editor at Harper’s and Rolling Stone. Four years earlier, while at Harper’s, Aron had learned of an enticing mystery. The brain of the late Albert Einstein, the greatest genius of the 20th century, had apparently gone missing. Now that Aron had a magazine to edit—and one dedicated to Einstein’s adopted state—it was time to take the mystery out of mothballs.

Aron remembers approaching his staff. “Who wants to see if they can find out what happened to Einstein’s brain?” he asked. Steven Levy, the young reporter who had written the account of teen prostitution in Sussex County, stepped forward.

Levy started his search at Princeton Medical Center, where Einstein had died in 1955. At Einstein’s request, his brain had been preserved for study. But 23 years later, no one had a clue where it was. Levy doggedly tracked it to a medical lab in Wichita, Kansas, where the pathologist who had removed the precious gray matter had preserved sizable pieces in two Mason jars. The jars were stashed in a box in his office—under a beer cooler. Mystery solved.

News of Levy’s first-person story, “My Search for Einstein’s Brain”—published by New Jersey Monthly in August 1978—went out on the AP wires and brought national attention to the young magazine. The popular broadcaster Paul Harvey did a radio segment on Levy’s piece. “He did a whole bit about how this little magazine in New Jersey had found Einstein’s brain,” recalls Aron. “That was a coup.”

“The big excitement for me,” Levy later wrote on his personal website, “was seeing those little brain pieces, each the size of a Goldenberg’s peanut chew, bobbing up and down in solution.”

Levy and Carpenter were stars of the early years. (The two were also an item; they met as fellow staffers and married in 1988.) Levy’s March 1979 New Jersey Monthly piece on the Educational Testing Service (which alleged that ETS covered up research indicating that coaching could improve SAT scores) was a National Magazine Awards finalist for public-service journalism. Carpenter, whom Aron fired when cutting staff in late 1979, won the Pulitzer Prize for feature writing in 1981 for her Village Voice article on the death of model/actress Dorothy Stratten.

Other future marquee names on the early team included Jerry Goodman, who served as editorial advisor and latergained fame as a financial writer under the pen name Adam Smith; columnist Marvin Kitman, a future Pulitzer Prize finalist; and John Harwood, who started with the first issue as an editorial assistant, went on to the Wall Street Journal and is now CNBC’s chief Washington correspondent. Future New York Times reporters who wrote for New Jersey Monthly include Michael Norman, Anthony DePalma and Randall Rothenberg.

“There were a lot of good people and smart people who were really into putting out a strong magazine,” recalls author and journalist Ben Yagoda, who served briefly as executive editor in 1982 and now teaches journalism at the University of Delaware.

But if the editorial team was feeling its oats, the business picture was not so pretty. After the first year, circulation had reached 100,000—far more than initial projections. That meant greater printing and mailing costs than budgeted. Niemann and Leach borrowed an additional $500,000 from a new group of investors, a debt that came back to haunt them. The magazine, though booming in readership and ad sales, lost $800,000 in 1977 and $450,000 in 1978. At least the size of the losses was heading in the right direction.

But the balance sheet was not the only problem. Stories by the feisty—and perhaps careless—editorial team were slammed with no less than nine libel suits in the early years. Two suits arose from the April 1980 cover story titled, “The Mafia Road Map and House Tour.” In another case, Resorts International sued over a May 1979 story that described its casino hotel as “Mob-tainted.” Shortly thereafter, a former state senator claimed he was defamed in an October 1979 piece that rated the state’s legislators. The story described him as “floundering and ineffectual.” In the latter two suits, the defendants demanded that the magazine reveal its sources. New Jersey Monthly fought back, and the two cases went all the way to the state Supreme Court, where the justices ruled 6 to 1 in the magazine’s favor, affirming that reporters and news organizations were protected against forced disclosure of their sources in libel actions. It was a landmark decision reinforcing New Jersey’s shield law for journalists.

New Jersey Monthly never lost any of these cases, but the legal costs were steep, and its insurance premiums quintupled. Eventually, Aron says, the spate of suits cost him his job as editor.

Oddly, by the magazine’s eighth issue, Niemann and Leach had changed hats, with the former assuming the publisher title and the latter becoming editor in chief. “We just realized we liked each other’s jobs better,” says Niemann. Whatever their roles, “they were quite a team,” says Aron. He speaks warmly of the founding duo, known around the office as Chris and Drix. “Chris was quiet, intellectual, brilliant and quirky,” he says. “Drix was hard-charging, energetic, incredibly hardworking and very smart in a different way.”

Unfortunately, the four remaining limited partners were losing patience. (The Hackensack Record had taken back its investment and pulled out of the company.) The limited partners controlled four seats on the magazine’s nine-person board. In March 1980, they swayed a fifth board member and staged what Niemann refers to as “the coup d’etat.” Arriving at what he thought was a routine board meeting, Niemann was sacked. Leach was asked to stay on and remained as editor in chief through the summer.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been as devastated before or since,” says Niemann. “Honestly, it never, ever, ever crossed our minds that that would happen.”

Aron, who was still editor at the time, recalls the upheaval. “The staff was shocked,” he says, “but like most young people in media organizations, they rolled with the punches.”

By early 1982, with the lawsuits dragging on and the magazine’s annual losses still running to six figures, New Jersey Monthly was on the brink of bankruptcy. The decision was made to sell. Norman B. Tomlinson Jr. of the Morristown Daily Record emerged as the buyer. “We were the only ones that were really interested in taking it over, which we did,” says Tomlinson. One by one, he bought out the other shareholders until the Daily Record held 95 percent of the company.

Unlike Niemann and Leach, Tomlinson had ink in his blood. His grandfather, Ernest, had founded the Daily Record in 1900. His father, Norman Sr., took it over shortly after World War I. The Tomlinson family had enjoyed eight decades of publishing success in New Jersey. Now, Norman Jr. had to pull a turnaround out of his hat.

Tomlinson took the reins as publisher, effective with the September 1982 issue. He brought in a new editor (Colleen Katz), cut staff, and moved the magazine from Princeton to Morristown, where it shared space and resources with the Daily Record. The new ownership also smoothed out the magazine’s edginess, moving away from its prior obsessions with crime, the Mafia, suburban scandals and political intrigue. Softer topics—home computing, brunch and cosmetic surgery—took over the front cover, although the new team continued to assign stories on consequential topics such as toxic waste and rising insurance costs.

“We wanted the magazine to be a survivor,” Tomlinson explains. Overall, the goal was to present a more positive picture of life in New Jersey. This, after all, was the era of Tom Kean’s governorship, epitomized by his TV campaign slogan, “New Jersey and You: Perfect Together.”

The magazine started to right itself. By its 10th-anniversary issue in November 1986, New Jersey Monthly had reported two consecutive years in the black. Circulation, which had declined, climbed back above 100,000—even at Tomlinson’s sharply increased subscription price. Ad pages were up, too.

Tomlinson turned his attention to another goal: getting out of the newspaper business. In 1987, he sold the Daily Record to the Goodson Newspaper Group. (In 1998, Goodson flipped it to current owner Gannett.) New Jersey Monthly now had Tomlinson’s full attention.

In February 1988, another Tomlinson—Norman’s daughter, Kate S. Tomlinson—made her first appearance on the masthead, joining as publisher. Norman took the title of president/editor in chief.

Kate Tomlinson grew up in Morristown, received a B.A. from Harvard and a Master’s in Soviet Studies from the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. None of her early employers—the Library of Congress, the Office of Technology Assessment, the U.S. International Trade Commission—suggested she was headed for a career in publishing (although she did edit and author technical publications in each case).

Kate plunged into her new vocation and learned quickly. Within months, her role grew to publisher/editor in chief (with Norman keeping the title of president). The challenges were substantial. With the newspaper gone, the magazine acquired new costs of printing and other services that had been provided by the Daily Record. “I remember being presented with the first bill for typesetting,” says Kate. There were real concerns about being able to pay.

To survive the disentanglement from the newspaper, costs were cut, and the sales team went into overdrive to acquire additional ad pages. It helped that the economy was booming. “Timing,” says Kate, “is everything.”

Father and daughter ran the publication in tandem until Norman’s retirement in early 2004. Established again as a stand-alone publication, the magazine thrived. For many of the state’s residents, reading the Shore Guide—introduced in 1977—became an annual June ritual as they anticipated summer weekends at the beach. Awaiting the results of the annual restaurant poll was another ritual. Taking cues from other regional magazines, New Jersey Monthly published its first Top Doctors edition in April 1992 and its first high school rankings that September. The Top 25 Restaurants list, introduced in 2007, became the arbiter of New Jersey culinary excellence.

As New Jersey Monthly celebrates its 40th anniversary, it stands tall as an island of stability and strength in the rough seas of New Jersey media. Competing magazines have fallen by the wayside. Virtually all of the state’s daily newspapers, fighting for their lives, have been rolled up into corporate entities. AOL has tried, and failed, to make inroads here. But New Jersey Monthly carries on, along with its sister publication, the twice-yearly New Jersey Bride, both still Jersey-owned by Kate Tomlinson. Last April, creative director Laura Baer unveiled the first complete redesign of NJM since 2005. In November, the magazine tilted the scales at a hefty 300 pages, among the biggest issues ever.

The magazine still endeavors to produce journalism that matters in areas of importance to its readers like health, education, politics, the environment. And just as in the beginning, the magazine also seeks to entertain and inform readers with coverage of all that’s great in the Garden State, including restaurants, culture, events and popular (or sometimes lesser-known) Jersey destinations. It covers fascinating celebrities with Jersey pedigrees, as well as ordinary neighbors who, through innovation, enterprise or philanthropy, help make New Jersey a better place.

The New Jersey Society of Professional Journalists and the national trade publication Folio have honored the magazine numerous times in recent years for excellence in editorial, photography and design. One of the magazine’s Folio winners, the January 2015 cover story, “Why New Jersey Roads Suck,” by associate editor Breanne McCarthy, reminded readers that New Jersey Monthly—even at 40—still has the feistiness it displayed in its younger days. Almost two years later, New Jersey has finally instituted the gas-tax increase needed to address the infrastructure issues detailed in that award-winning piece.

In recent years, the magazine has also written about the troubled rollout of New Jersey’s medical marijuana program, Camden’s new street-oriented police force, the threats to our environment from invasive species, the difficulties facing autistic adults, the PARCC testing controversy, Atlantic City’s troubles and Jersey City’s boom.

The continued vitality of the magazine is just part of the picture. Today, more people read New Jersey Monthly online than in print—a vindication of the magazine’s commitment to digital publishing. In the past year, New Jersey Monthly launched its third digital newsletter; combined, the three free newsletters have more than 140,000 subscribers. The magazine also launched its first podcast, Eating With Eric, hosted by deputy editor/dining editor Eric Levin. Traffic to the njmonthly.com website has helped extend the brand to a new generation of readers. Page views and unique visitors to the site are on a steady upward trajectory, reaching new peaks this year.

“We look forward to a future,” says Tomlinson, “in which we tell the stories of importance to New Jerseyans in the medium that best suits them.”

Ken Schlager has been editor of New Jersey Monthly since April 2008. He is the longest-serving editor in the magazine’s history.