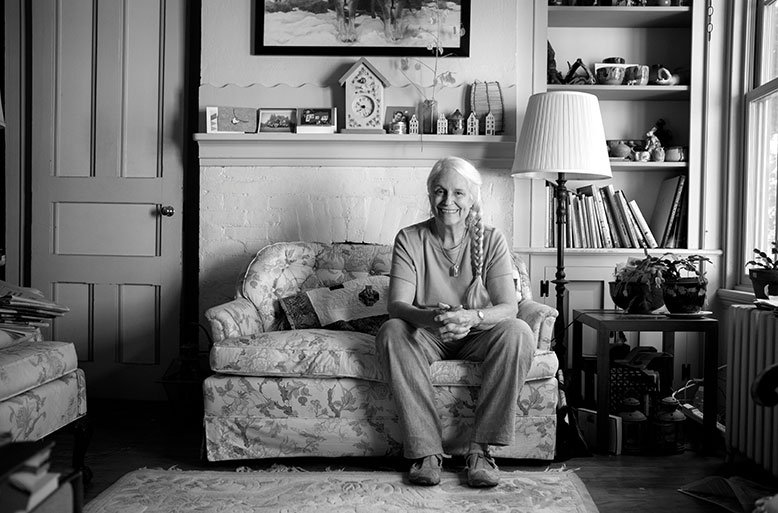

“I was a child hearing her mother sing for the first time.” – Joi Fisher Photo by Chad Hunt

Joi Fisher’s reunion with her birth mother evolved slowly and profoundly. The woman wanted to meet at her church in Asbury Park on a day in February when she would be giving testimony.

Fisher, who lives in Piscataway, traveled to the small, brick church with her adoptive parents. They sat near the back as her birth mother sang “It’s Working,” a gospel song with these lyrics: “This is my season for grace for favor/This is my season to reap what I have sown.”

It was a powerful moment for Fisher, 47. “I was a child hearing her mother sing for the first time,” she says.

Fisher’s mother told the congregation of lying prostrate years ago at the altar of her former church, bereft, asking what more God could take from her. She spoke of how, over time, the joy of salvation was restored to her. And, to the surprise of the parish members, she revealed that she had placed a baby for adoption and today would be holding her in her arms for the first time. Yes, God has given her back her joy.

She invited “my Joi” and her adoptive parents to the altar. As they embraced, tears flowed.

“When I hugged her,” says Fisher, “I felt like I was going to collapse.”

Fisher’s reunion story is one of many being shared around New Jersey this year. In January, adoptees in the state gained legal access to their birth records for the first time; as of mid-August, more than 3,500 had received their original birth certificates from the state. After requesting the information, they had watched the mail for an envelope from the Department of Health that would—perhaps—include the names, hometowns and birth dates of their birth parents, and maybe even the names they had been given at birth.

It took 34 years of lobbying by the New Jersey Coalition for Adoption Reform and Education (NJCARE), a Morristown-based advocacy group, for the state to pass the birth-records bill. Now New Jersey no longer stands in the way of adult adoptees who wish to contact their birth families and gain a deeper understanding of their roots, or those who need crucial information about their medical history. The bill included a 30-month waiting period, which allowed birth parents time to ask the state to redact their names if they wished.

New Jersey is one of 10 states to allow such access to birth records. Among neighboring states, Jersey is breaking new ground. Pennsylvania has passed a law like New Jersey’s; it takes effect in November. Advocates have been working in New York for 23 years for access to original birth certificates; a bill that allows such records to be released on a case-by-case basis, requiring court review, is awaiting the governor’s signature. Some advocates call the New York bill too restrictive. Connecticut allows people born since October 1, 1983, to access their original birth certificates; a pending bill would give all adoptees access.

For some adult adoptees, access to their original birth certificates is a matter of life and death. That’s because an understanding of family medical history can save lives. For example, based on family history, one can opt for more frequent screenings to detect specific cancers or choose relevant genetic tests that help predict risk for certain diseases. Results of such test can suggest changes in diet or lifestyle. Open records advocates in New Jersey and New York named five adult adoptees in recent memory believed to have died prematurely due to lack of access to their medical histories.

For Fisher, an assistant principal at Piscataway High School, the original birth certificate means power and knowledge—and no longer having to leave blanks in health histories and family trees.

“Every time you go to a new doctor, you never escape it,” she says. “People seem to think being adopted goes away, but we live with that every time we go to the doctor…. There are things I want to know.”

READ MORE: A Tale of Two Sisters.

Opening birth records raises complex ethical and practical issues. Birth stories can be fraught with shame, infidelity, sexual assault and other painful episodes older generations preferred to keep quiet. Legislators must weigh whether the adult adoptee’s desire for knowledge of his or her origins outweigh the birth parents’ desire for privacy.

But according to a 2001 academic report by University of Baltimore School of Law professor Elizabeth J. Samuels, the paperwork birth parents signed did not promise them anonymity, and adoption records were sealed to protect adoptive families from birth parents, not to protect birth parents from adult adoptees. In fact, the American Adoption Congress reports that, in eight states where a total of 44,000 records were requested, less than 2 percent of birth parents—only 757—asked to have their names removed from records.

“How does a state have the authority to remove evidence of an individual’s identity at birth?” – Pam Hasegawa Photo by Chad Hunt

Five years ago, Carly Dethorn, who was born and raised in New Jersey, had a pressing need to obtain her birth records. Her son needed a kidney transplant. She did all she could to find her birth family and, potentially, a donor. A New Jersey judge refused to unseal her adoption records, despite her son’s dire condition. (He eventually received a kidney donation from a friend.) It wasn’t until this year that Dethorn, now 73 and living in Wilmington, North Carolina, received her original birth certificate. It lists her parents as Carrie Umbaugh Federowicz and Frank Federowicz, both now deceased.

But part of Dethorn’s history remains a mystery. She learned that Frank Federowicz was her mother’s husband, but not her birth father. He was storming the beaches of Normandy when Carly was conceived. When he came home from the war and learned that Carrie had had an affair and gotten pregnant, Frank had a nervous breakdown. The couple stayed married for 53 years, but never had children. Frank even agreed to put his name on the baby’s birth certificate, though it contains the notation “o.w.,” for “out of wedlock.”

“It’s a closure, or an opening—both really,” Dethorn says of her new understanding of her beginnings. “I probably know more about my birth family now than some people know about their families.”

Dethorn connected with Carrie’s last remaining sibling, a 98-year-old aunt, Frances, in Pennsylvania. Carrie’s last caretaker, a niece by marriage named Mary, now considers Dethorn a sister and has given her precious mementos, including Carrie’s wedding band, pearls that Frank had given Carrie, and a great-great-grandmother’s quilt. Carrie tried to refuse the gifts, but the niece insisted.

Dethorn still hopes to find her biological father, pursuing a name or two that family members recall (it may be Sylvestro), though none had heard much more than rumors that Carrie had had a child. From various relatives, Dethorn has learned that Carrie used to sport a very tall hairdo and sleep with her head hanging off the side of the bed to keep it neat. Friends compared Carrie to the Energizer Bunny, a character whose high metabolism Dethorn shares. She also learned that Carrie passed away in Bradenton, Florida, where Dethorn’s daughter lives, a town Dethorn has visited frequently. She also learned that Carrie’s memorial service was held on October 13, the birthday of both the niece’s granddaughter and Dethorn’s.

Such coincidences often emerge when birth families and adoptees share their stories. One New Jersey adoptee who found his birth mother through the new law discovered that he had gone to the same college, a year behind his biological half brother, and in fact had been the best man at a wedding where his half brother’s wife had been a bridesmaid. Some adoptees find they have lived in the same cities as their birth families at different times.

For other adoptees, an original birth certificate does not tell the whole story. Robert MacNish, who lives in New Milford, learned recently that his birth mother had filled in the birth certificate with a surname she and her mother had made up out of the blue. MacNish describes himself as a “replacement child,” adopted after his adoptive parents’ first son died of pneumonia at age seven. He was 22 when his father told him he was adopted. With the help of a search angel—a volunteer who constructs family trees from DNA information and available clues—he has met his birth mother, Jean, now 95. She cried and told him she had thought about him every day for the last 73 years—his entire life.

Likewise, Pam Hasegawa’s birth mother gave a false name on Hasegawa’s original birth certificate. Hasegawa, the spokesperson for NJCARE, was able to find birth relatives only through DNA testing.

Since 1980, Hasegawa has helped lead the battle to make adoptees’ original birth certificates accessible in the state and received the Friend of Children and Youth Award from the North American Council on Adoptable Children in July. She enjoyed the recent legislative victory.

“It’s so nice that we’re celebrating something so simple,” she says. “A birth certificate is a government document attesting to the birth of an individual given birth to by a mother who was impregnated by a father. How does a state have the authority to remove evidence of an individual’s identity at birth?”

“I now know that there’s someome that’s my brother…and he and I can talk on the phone and see each other. It’s a whole different world.” – Gary Ruckelshaus Photo by Chad Hunt

The new law was exactly what Gary Ruckelshaus, 69, needed to find his birth family. A former mayor of Madison, he personally thanked Governor Chris Christie for signing the law.

“He changed my life and probably the lives of thousands of other people,” Ruckelshaus says. “I now know that there’s someone that’s my brother, for goodness sakes, and he and I can now talk on the phone and see each other. It’s a whole different world.”

Over the years, a few adoptees were able to gain access to their adoption records by convincing a judge that their mental health required it. In the mid 1990s, Ruckelshaus had asked a judge to unseal his records, but after an interview with a psychiatrist, he was deemed too well-adjusted to need the court order from the judge. “I’ll never forget the words he used: ‘I never opened one of these records before, and I’m not going to start now.’”

Ruckelshaus then hired a private investigator, who found the last name of his birth mother, Patterson. Ruckelshaus wrote letters to every Patterson near Troy, New York, where he was born. He heard back from one promising lead, but their DNA did not match.

He met Hasegawa at a wedding and became active in NJCARE’s lobbying efforts to open birth records. He spoke to legislators, many of whom he knew from local government. His efforts—and the work of others—were met with opposition from anti-abortion groups and the NJ Catholic Conference. In 2011, Christie vetoed a bill to open the records.

“I gave up,” Ruckelshaus says. “I made the decision that, at that point, I’d go to my death never knowing about my birth parents or if I had siblings.”

But in 2014, Christie signed a new version of the bill, this time with a provision to give birth parents the option to redact their names from the original birth certificates. On January 12—after placing several calls to the state health department to ask what was taking so long— Ruckelshaus received his original birth certificate with his birth mother’s name, Virginia Patterson. Through classmates.com he found her senior picture from her high school yearbook. She had a white collar, wore her hair brushed back from her forehead and looked quite a bit like him.

“That was probably the most significant thing of the whole search,” he says. “The face to go with all the knowledge I was gaining.”

From his birth mother’s obituary, he found the name of a son, Glenn P. Davis of Lynnwood, Washington, his half brother. He sent him a registered letter and heard back within a week. By late June, DNA test results proved they were related.

Davis, who had thought he was an only child, is floored that his mother took the secret of his older half brother’s birth to the grave. “I’m sad for her, when I think of that part of it, and sad that I didn’t have a brother to share my life with,” he says. “As a little brother, I think he could have helped me out a bit.”

Davis, who plans to meet with Ruckelshaus and two cousins in December, feels angry at the judge who kept his big brother’s original birth certificate sealed.

“If the judge had allowed this to happen, my mom was still alive back then, and they would’ve been reunited,” he says.

In March, Joi Fisher met her birth father. He brought her a copy of her great-great-grandfather’s diploma from Tuskegee Institute, signed by Booker T. Washington. Now her daughters are also benefiting from her newfound family. They have learned their ancestors were involved in the sciences.

“My daughter Traci walks around in the summer with an anatomy book, and when she found out there were all these doctors in the family and people interested in science, she said, ‘Now I don’t feel so weird anymore. I was built for this.’”

It was an emotional meeting, not just for the newfound relatives. One of Fisher’s adoptive aunts, quite moved by the reunion, told her she had never met her own father, even though she had not been adopted.

Fisher’s adoptive parents have adjusted to the latest developments and have met many of her new relatives. In fact, they had encouraged her search; she learned of the changing law in the news clippings her father sent her regularly. Fisher has attended several adoption-related support-group meetings—one group gathers monthly in Morristown, another in Pennington—as she ponders this new chapter in her life.

“Right now,” she says, “I’m just trying not to worry about how to divide myself, to have enough time for everybody.”

Tina Kelley is co-author of Almost Home: Helping Kids Move from Homelessness to Hope (Wiley, 2012) and a former New York Times reporter. She lives in Maplewood.

Loved this article. Thanks.

So excited to receive my PA original birth certificate. I am not interested in ruining anyone’s life; I hope eventually to expand my “family.”

I was one of 4 plaintiffs who sued NJ for my birth certificate in the late 70’s. We lost in court. By the time I got my birth certificate in January I had already figured out who my birth mother was through my own investigations over the years and DNA testing with Ancestry. I worked pretty hard to get information that the State kept from me for so long.

I’m sorry they screwed you (and all of us) over. Were you ever able to connect with anyone in your birth family? I’ve been trying through DNA with Ancestry, but not having much luck.

Found my birth father’s identity thru Ancestry long after he passed away but his relatives have been very welcoming. Bio-mom still lives in secrecy and I don’t even try to approach her family. Ancestry is amazing for adoptees but you have to be patient. Good luck.

Why not approach your birth mother’s family? No doubt a few of them wondered about that blank year in her life. And what would they do if they knew the whole story? I’d guess they’d talk about it briefly and wonder how you’re doing.

Due to the secrecy laws prohibiting people born in NY City from obtaining their birth certificates, I was unable to find my birth parents. But after a few decades, my birth father turned up. By connecting with him, I learned that my birth mother had been dead for 20 years. Despite never meeting her, when I got the news, it hit pretty hard. Learning of her death made it real.

You can try through an adoption registry. Once I received my Birth Certificate (NJ) I went through gsadoptionregistry.com. Their search angels are amazing people. I actually found my birth mother in 3 days with their help and Ancestry. Unfortunately a reunion with her seems pretty hopeless right now. I do have 2 half sisters that I may try and reach out to. Not giving up yet!