When an artist friend was chosen to create a Black Lives Matter mural for the city of Orange, I was quick to volunteer my help. Inspired, and frankly a bit awed, by the social-justice movement sweeping the country and the world, I had only participated in quiet ways—a donation, a petition, a Twitter conversation—but this was a chance to get my hands dirty.

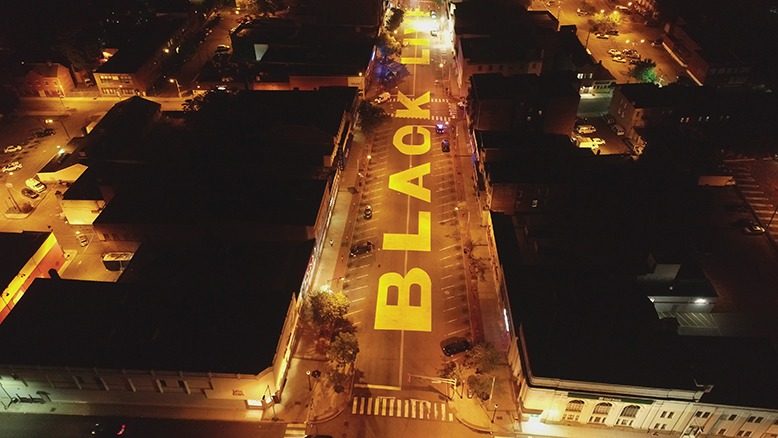

The parameters of the project were daunting; each of the 16 letters would be 35 feet by 50 feet. The message would be painted down Main Street in Orange, the length of four football fields. Luckily, the artist, East Orange native Sterling Brown, a portraitist, sculptor and muralist, had worked on projects of this magnitude before. My participation would be as worker bee, snapping chalk lines and holding the measuring tape; Brown would orchestrate the design. The letters we sketched in advance would be painted in by volunteers at a community event.

Artist Sterling Brown, who designed this BLM mural, with local activist Robert (RJ) Gibbs.

The first day, our team of four arrived on the scene at 8 pm (after the business district closed) to find barricades blocking the street, police rerouting traffic and council members cheering us on. The fire department pitched in with a rolling floodlight, and city workers were at the ready to assist with a street-striping machine to reinforce the outlines of the letters. An uneasy irony went without mention; law enforcement was on hand to support a protest movement at which the police stand in the uncomfortable center.

Orange’s mural is the nation’s largest (so far), but similar statements have been painted on streets in 64 cities across the country—eight in New Jersey, with more planned—as well as Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom. As with the other murals, the Orange project was conceived as a command, a reminder and a plea to end police brutality against Black people.

[RELATED: The New Us: Stories of Resilience and Hope]

Rain delays and supply-chain issues (we had to wait for Sherwin-Williams to order more street paint) slowed our progress. I worried that the holdup might put a damper on community participation. It didn’t. Masked and ready, exuberant volunteers came out to fill in the letters. They were young and old, mostly Black, but also Latinx, Asian and white. There was music, dancing and laughter.

Community members join the painting project.

As I made my way among the volunteers, helping move supplies along the four-block stretch, I took in bits of conversations: “I’m honored to be a part of this.” “We’re not going back.” “This will make people think.”

I don’t know whether the Black Lives Matter murals will help stop racial profiling, but I am sure this art matters. All of the murals represent a potent call for change from the communities that come together to create them.