In the summer of 1958, Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov’s book Lolita made its U.S. debut. Americans were introduced to the novel’s narrator, a middle-aged man named Humbert Humbert, who tells the story of his obsession with a 12-year-old girl named Dolores “Dolly” Haze—Humbert calls her his Lolita—and the sexual relationship he forces her into during a cross-country journey. Lolita, with its lyrical prose, would become one of the most celebrated and controversial books of its time.

Now, 60 years later, in her new book, The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel that Scandalized the World (Ecco Books), author Sarah Weinman shines a spotlight on the long-forgotten girl from New Jersey who inspired the tale.

“Knowing about Sally Horner’s story helps us not only understand what is really going on with this iconic piece of 20th-century literature,” says Weinman, “but it highlights all the ways in which we have failed girls and women.”

The Real Lolita arrives at a crucial moment in our culture, as the #MeToo movement highlights stories and experiences of girls and women who have been victimized by men. Sally’s story is part of that reckoning.

On June 14, 1948, Ella Horner watched as her 11-year-old daughter, Florence “Sally” Horner, boarded a bus from her hometown of Camden to Atlantic City, supposedly for a weeklong beach vacation with a friend. Sally wouldn’t return home for almost two years.

What Sally hadn’t told her mother was that, just a few months earlier, she had been caught stealing a notebook from the Woolworth’s in Camden. Acting on a dare from some of her classmates, Sally had picked up a five-cent notebook and shoved it into her bag. Before she could leave the building, a middle-aged man grabbed her arm. “I am an FBI agent,” the man told Sally. “And you are under arrest.”

The man was not with the FBI or any other law-enforcement agency. He wasn’t a security guard for the store. He was Frank La Salle, a 50-year-old convicted child molester. He had been released on parole two months earlier after serving time for the statutory rape of five girls, ages 12 to 14.

Of course, Sally didn’t know this and feared she was about to be thrown in jail. The man told her he’d let her go as long as she reported back to him “from time to time.” If she didn’t, he would place her in a reform school. Sally agreed to his rules, relieved she wouldn’t have to call her single mother from prison.

In mid-June, La Salle stopped Sally again, this time on her walk home from Northeast School, where she had just finished fifth grade. He had new instructions: Sally had to go to Atlantic City with him. She was to tell her mother she had been invited on a week-long Jersey Shore vacation with a friend’s family.

Ella agreed to let Sally go and walked her the few blocks from their house at 944 Linden Street to the Camden bus depot. There she saw Sally join a man whom she assumed was Sally’s friend’s father.

From Atlantic City, Sally wrote letters to her mother, asking permission to stay a little longer. One week stretched into two, then three, then four. On July 31, 1948, Ella received the last letter from Sally. In it, Sally told her mom, “I don’t want to write anymore.” Ella called the police, and a search for Sally began on August 5. But by the time two Camden detectives arrived at 203 Pacific Avenue in Atlantic City, the return address on Sally’s letters, the 11-year-old and her abductor were gone.

Over the next 21 months, Sally was held captive and repeatedly assaulted as La Salle fled from Atlantic City to Baltimore and then to Dallas, where La Salle found work as a car mechanic and Sally posed as his daughter. The next and final stop was San Jose, California, where Sally finally managed to phone home for help.

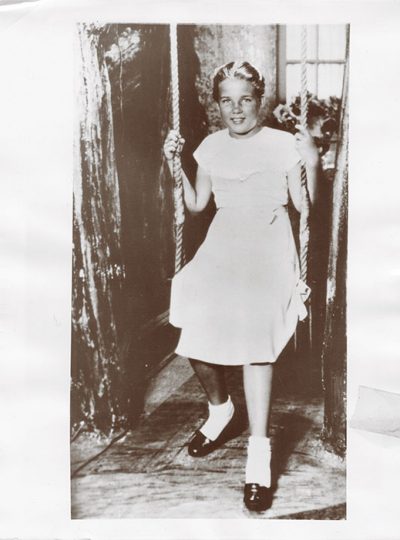

Sally leans on her mother, Ella Horner, minutes after being reunited. Photo by International News Photos/courtesy of Sarah Weinman

On March 31, 1950, Sally boarded a plane with a Camden County prosecutor en route to Philadelphia International Airport, where she would be reunited with her mother, Ella, and her older sister, Susan, who had given birth to a baby girl while Sally was in captivity.

Frank La Salle was arrested, charged under the Mann Act, and sentenced to 30–35 years in prison. Sally’s story took an even more tragic turn when, two years after returning home to Camden, she was killed in a car accident in Woodbine on her way home from a trip to the Shore. She was 15 years old.

Nabokov never admitted that Sally Horner’s story played a major part in the genesis of Lolita. In fact, he denied it, even when journalists and literary critics started drawing parallels between Sally’s story and Lolita’s plot as early as 1963.

As Weinman shows in The Real Lolita, there are undeniable connections between Nabokov’s book and Sally’s story, starting with a line from Chapter 33, where Humbert muses to himself, “Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?”

To further confirm the link, Weinman draws on old newspaper clippings and Nabokov’s archives at the New York Public Library and at the Library of Congress, where she found proof that the author had, in fact, read about Sally while working on Lolita. His notecard collection included one on which he had transcribed the AP announcement of Sally Horner’s death, which included facts about her 21-month captivity.

While researching the book, Weinman also drew on court transcripts and ancestry reports, and sought out anyone who might have known Sally. She searched archives in towns and cities all over New Jersey, including Camden, Trenton and Wildwood. On research trips, the Brooklyn-based Weinman would take the Northeast Corridor train from New York Penn Station to Trenton, where she’d catch the River Line and head further south toward Camden.

“Almost every stop along the way correlated to some city connected to Sally,” she says, starting in Trenton, where Sally was born; then Roebling, where Sally had lived as a baby; and then through Florence Township, where Sally spent the summer of 1950 with her sister Susan’s family after returning home.

On the anniversary of Sally’s death, Weinman made a trip to Wildwood, the last place Sally had been seen alive. She walked the boardwalk twice: once by day, and once by night. “I wanted to see if it was possible to feel some remnant of what Sally might have felt,” she says. “I wanted her to be as alive as possible in those pages.”

Not many people who knew Sally are alive today. Her niece, Diana Chiemingo, now 70, who was born in August 1948, two months into Sally’s captivity, is one of them. Chiemingo, who lives in Burlington, was four when Sally died and lived much of her life unaware of her family’s connection to Lolita.

She doesn’t recall much about her aunt, but she can speak to the tragedy’s impact. “You never think this could happen to someone in your family,” she says. “My mom and grandmom survived a horrible family challenge.”

Chiemingo looks forward to the response to The Real Lolita. “The story doesn’t have a happily-ever-after-ending,” she says, “but it is an important story of a true-life survival that needs to be told.”

For Weinman, it feels like a crucial time to rediscover the story. “Sally matters because girls and women matter,” she says, “and it behooves us never to forget that.”