In 1978, when Karen Kessler was a newly minted graduate of Vassar College, she wrangled an invitation to meet Stewart Mott, a New York philanthropist and heir to the GM fortune.

The invitation had required some maneuvering. Mott was one of 50 notable people to whom Kessler had written in hopes of putting her economics degree to use working for someone interesting. In that department, Mott did not disappoint. Kessler, then 22 and still living at Vassar, arrived at Mott’s Park Avenue apartment in a crisp, navy suit after consulting the classic book Dress for Success. Mott, 42, lived in his building’s penthouse; he greeted her at the elevator wearing nothing but cargo shorts.

What happened next was not exactly a MeToo moment. “If I had been smarter, if I hadn’t been so serious about getting a job, I would have run out of there,” she says. Instead, “I stuck my hand out and said, ‘Mr. Mott, I’m here to talk about my career.’”

Mott probably found Kessler to be overly focused, she says. But it didn’t prevent him from offering her a job as the manager of his foundation, a multimillion-dollar organization that funded groups opposing nuclear weapons and those supporting family planning. She negotiated a starting salary of $14,500 a year.

Kessler has come a long way since, although she never quite managed to put a lot of distance between herself and the kind of high-profile men who expect to get away with parading around in cargo shorts and worse.

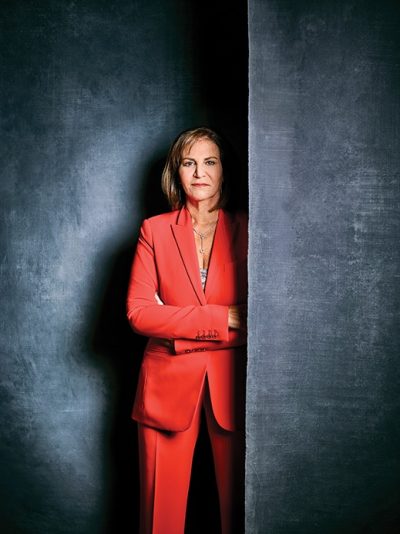

Kessler is cofounder and president of Evergreen Partners, a Warren Township company where celebrities, politicians and moguls outsource their personal crises. You’ve never heard of Evergreen for a reason. “We’re stealth,” says Kessler, whose short list of publicly known clients include embattled mixed-martial-arts superstar Conor McGregor and the football Giants. (Kessler won’t identify their specific controversies.) The law firm representing former Port Authority chairman David Samson brought in Kessler to run interference during the Bridgegate scandal in 2014. A year later, Kessler worked with the law firm representing Dr. Zyad Younan, the Holmdel physician whose countersuit against a New York strip club helped law enforcement build a case against a band of New York strippers who drugged men and robbed them. The scheming-strippers brouhaha gave rise to the movie Hustlers, released in September and starring Jennifer Lopez.

“If it’s happening in the New York–New Jersey market and it’s somewhat salacious,” says Kessler, “there’s a likelihood we got a call about it.”

At least one client was so salacious that Evergreen ultimately turned him down. In 2016, Donald Trump, then a presidential candidate, had his lawyer call Evergreen on behalf of his embattled friend Roger Ailes, then the chairman of Fox News. Viewers of the 2018 documentary Divide and Conquer: The Story of Roger Ailes, in which Kessler appears, know what happened next. Those who missed the documentary can get a sense of the maelstrom Evergreen nearly stepped into via the major motion picture Bombshell, out this month. It stars Nicole Kidman as Fox personality Gretchen Carlson, the first of more than a dozen women who would accuse Ailes of sexual harassment. The Ailes debacle is also the subject of a Showtime miniseries The Loudest Voice, based on the best-selling book The Loudest Voice in the Room (Random House, 2014) by Gabriel Sherman.

Bombshell director Jay Roach called on Kessler during his research for the film. She is accustomed to such inquiries.

“We get really exciting phone calls all the time,” Kessler says. She’s seated at the head of Evergreen’s conference-room table on a late summer afternoon. Film noir posters—Cary Grant in Crisis, Robert Hutton in Scandal, Incorporated—decorate the walls. They telegraph a message she doesn’t have to work hard to get across: Though her business, which she launched 26 years ago with Mindy Cohen, a friend who is now retired, is dead serious, Kessler isn’t. “We like to joke around here that our first meeting with a client is like a colonoscopy. Stuff comes out,” she says. “I know that’s gross and you’re appalled.”

* * *

Confidentiality agreements prevent Kessler from discussing most of the exciting calls she and her staff of six fellow damage controllers field. But in general, Evergreen’s clientele is “a mix of celebrities, politicians, not-for-profits, big universities, Fortune 500 companies, and hospitality businesses, like restaurants,” she says. They come from all over the world, though they are mostly from the region. She has represented officials at all levels of New Jersey government. Often it’s a lawyer who reaches out first.

Lately they’ve been reaching out more than ever. In the last five years, the scale and scope of disasters landing in Evergreen’s lap has expanded “significantly,” Kessler says. That’s due in part to the proliferation of social media and MeToo cases. But the explosiveness surrounding Ailes, who died in 2017, appears to have boosted public awareness of Evergreen’s work. Divide and Conquer, the documentary Kessler appears in with colleague Warren Cooper, details the chairman’s profligate arrogance and chauvinism, as well as his gift for shaping American politics. To understand how Evergreen crossed paths with him requires some backtracking to the 2016 call from Trump’s lawyer, a tax attorney.

“Initially, we were told it was a contractual dispute with someone whose contract was up,” Kessler says, in reference to Carlson. “We saw that her ratings had gone down, and we thought it was a business matter, and that they have the right to hire and fire as they see fit.” Then Kessler and Cooper sat down with Ailes and his wife, Elizabeth, in the bunker-like living room at their home in Cresskill. When Kessler explained to Ailes that most harassment cases aren’t worth the negative publicity of going to court, Elizabeth, Kessler says, leapt out of her chair, incensed. “She said, ‘We will never settle this case. You need to understand something: Roger is more important than America,’” Kessler tells the Divide and Conquer interviewer.

Kessler and Cooper were flabbergasted. “We looked at each other and said, ‘What have we gotten ourselves into?’” says Kessler. Their dealings with Fox turned ugly. “Everything they wanted us to do,” including writing statements suggesting that Carlson was lying, “made us uncomfortable. And the more we said no, the harder they pressed.” Eventually, they turned the tables and represented a number of the women who had accused Ailes of harassment.

Kessler and Cooper were able to tell their story for Alexis Bloom, director of Divide and Conquer, because they refused payment and hadn’t signed a contract or a nondisclosure agreement with Fox—and also because they hated the ethical breaches they had witnessed there. Though they often breathe the noxious air emitted by punctured egos, they are steadfast in their standards. “We’ve walked away from numerous jobs for ethical reasons,” Kessler says. There is nothing partisan about it: “We’ve worked with 30 politicians, if not more than that, including lots and lots of Republicans.”

That is not to say Kessler is apolitical. Before she and Cohen opened Evergreen, Kessler was finance director for Democrat Jim Florio’s campaigns for governor in 1989 and 1993, and when he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for the U.S. Senate in 2000. She still considers him a close friend. She also worked for Arthur Levitt, the longest-serving chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, appointed by Bill Clinton. And she was an inaugural director of the Democratic National Committee’s Northeast office in the 1980s. In the conference room, where she has gathered all six of Evergreen’s crisis managers, almost everyone, including Kessler, has no problem admitting they are not partial to Fox News.

All, though, are news junkies so keenly attuned to the country’s cultural rhythms that they can practically divine what scandal will land on the front page next. Kessler says research—deep dives into the background of every potential client—drives the company. That, and the ability to read a room.

“Certain things don’t sell in this office,” Kessler says. For example, “when a guy walks in and says, ‘I swear to God it was consensual,’ and he’s 65 and she’s 21, I’ll say, ‘Let’s talk about the truth.’ We have to be able to cut through that stuff.”

* * *

Kessler’s ability to cut through the…let’s call it nonsense…is legendary not only among the lawyers who rely on her to liberate clients from their halls of shame, but also among her colleagues in the tiny field of crisis communications.

“Karen is calm and cool in a crisis situation, which is a very rare commodity,” says Mike DuHaime, a partner at Mercury Public Affairs and Chris Christie’s chief strategist during his two gubernatorial campaigns. DuHaime, of Westfield, has known Kessler for more than a decade through what he calls a “small niche” of people who have experienced upper-echelon crisis handling. “She’s also unafraid to speak truth to power, which is important, because in a crisis situation, you want someone who’s going to tell you a difficult truth. Karen doesn’t sugarcoat.”

Though that kind of straight shooting is not closely associated with Hollywood types, they seem to value it in Kessler. In the last decade, she has accepted consulting gigs on TV series including The Good Wife and Nashville, where she helped untangle impossibly messy plots and the characters who set them in motion. (Her brother, the producer Todd Kessler, worked on both shows.) She has also been a consultant on the Today show.

Kessler’s skill at wading through innuendo, rumors and half-truths undoubtedly came in handy while she was raising her three daughters, Liza, Nina and Julia. Liza works in financial-services marketing. Nina makes documentaries. Julia works on Cory Booker’s Senate staff in Newark. “I started telling them when they were very young, everybody has to be able to support themselves,” Kessler says. “You never know where life is going to go.”

That includes Kessler’s own life. At the time of our summer interview, Kessler had recently moved to Interlaken. She was in the process of selling the Warren house she and her ex-husband had bought 30 years earlier; they divorced in 2014. She is open to the possibility of meeting someone new, though that person will have to be okay with a partner who steals away regularly for secret meetings with prominent people and refuses to spill the details after. Recently, a client called and asked her to find a restaurant where no one would recognize them before the client had a meeting with the FBI.

“If you know somebody interesting…” she says, hinting that she’s ready to date. What she does not have to say: Those who have a slippery relationship with the truth or can’t keep a secret need not apply.