The first time Lesley Risinger helped free a man wrongfully convicted of a crime, she was a 33-year-old stay-at-home mother of three, living in Kearny, with no legal training and no more than an amateur interest in the law.

But as she read the story of Luis Kevin Rojas in the Jersey Journal in 1991, something about the 18-year-old Hudson County man’s claim that he had not committed the Manhattan murder, for which he was facing a 15-year sentence, struck her as believable, compelling and requiring her immediate intervention.

Risinger showed the article to her mother, Priscilla Read Chenoweth, a lawyer who had quit private practice and was working as an editor at the New Jersey Law Journal in Newark. The two began a seven-year crusade to exonerate Rojas who, they came to believe, was a victim of mistaken identity. Chenoweth took the role of lead counsel, pouring $65,000 of her retirement savings into investigators and additional lawyers.

Risinger assisted with research, writing and seeking new evidence.

Thanks to their years of hard work, the appelate court granted an appeal in 1995. At a retrial in 1998, new evidence unearthed by mother, daughter and their team helped set Rojas free.

“They stepped up to the plate and they helped me,” says Rojas, now 41 and an electrical engineer. “I’m here today because of them.”

That case lit a fire in Risinger, a tall, lean woman with ramrod posture and an earnest manner. She found the experience “exhilarating,” she admits with a twinge of guilt, because “there was nothing exhilarating about it for him.”

Nevertheless, it proved pivotal in her life, prompting her to finish her undergraduate degree and go on to Seton Hall University School of Law. In 2006, three years after passing the bar, she plunged into a second exoneration case. Fernando Bermudez, a New York man, had served more than 18 years for murder.

Risinger got the indictment dismissed after eyewitnesses changed their stories and prosecutorial and police misconduct were proven. In the courtroom, Bermudez engulfed Risinger in a bear hug, his face contorted in pain and relief.

“Lesley is just a remarkable person, a beautiful person inside and out,” says Bermudez, who now lives in Connecticut with his wife and the two youngest of his three children. “She definitely helped change my life for the better.”

With two exonerations under her belt, Risinger began to see this work as her “calling.” So in 2011 she launched the Last Resort Exoneration Project, the first organization devoted exclusively to freeing wrongfully convicted prisoners in New Jersey.

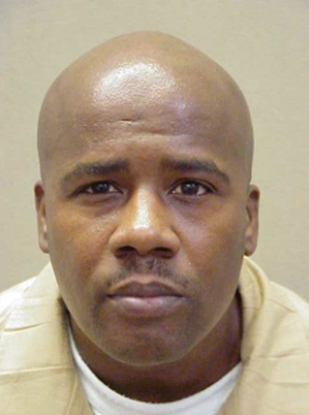

The Exoneration Project’s first client, Kevin Baker, has served nearly 19 years of a 60-years-to-life sentence for two murders. Courtesy of NJ Department of Corrections

In January of this year, after two years of reviewing potential cases, Risinger announced the Project’s first client: Kevin Baker, a small-time drug dealer from the Centerville section of Camden who was 25 when he was convicted of the 1995 execution-style killing of a man and woman from his neighborhood. Baker has served nearly 19 years of a 60-years-to-life sentence, but Risinger believes him to be the victim of a “perfect storm of misfeasance” involving every corner of the criminal justice system. For her, it is never too late to right a wrong.

Risinger named the Last Resort Exoneration Project after a legal initiative—the Court of Last Resort—launched more than 60 years ago by lawyer and mystery writer Erle Stanley Gardner, best known as the creator of the infallible defense attorney Perry Mason, played on television by Raymond Burr. Based at Seton Hall Law in Newark, where Risinger is an adjunct professor, the Project draws on the legal expertise of her husband, Michael, 68, a senior Seton Hall law professor and nationally recognized authority on evidence, who is cofounder and assistant director of the project. They met—each was divorced at the time—when she took his advanced evidence class in 2001.

Funded by private donors and support from the law school, the Project advocates for prisoners the Risingers believe are “actually innocent,” she says, not just convicted through procedural errors or an unfair trial. Similar projects around the country often use DNA evidence to establish their clients’ innocence. (The New York-based Innocence Project, for example, is attempting to use DNA evidence to exonerate former Elizabeth resident Gerard Richardson, who was convicted of a 1994 murder in Somerset County.) The Risingers also will consider cases in which DNA evidence is unavailable or inconclusive, but in which they believe new facts or a reexamination of existing evidence could well establish innocence.

Innocence, of course, is a slippery concept, especially hard to prove in the absence of conclusive DNA evidence. By Risinger’s count, at least 10 innocent men have been set free in New Jersey in the last 17 years. (The National Registry of Exonerations, a project based at two Midwestern law schools, counts 15 exonerations in New Jersey in the last 24 years.) There are no official figures on exonerations in New Jersey or elsewhere.

It is also difficult to know how many prisoners are doing time for crimes they did not commit. Paul Cates, spokesman for the Innocence Project in New York, says his organization figures the range is from 2.3 to 5 percent. The most conservative estimate from the exoneration community nationally is about 1 percent. In New Jersey, where Risinger’s group says about 5,498 convicts are serving sentences of 15 years or more, that would mean 55 innocents. With no government body devoted to helping felons claiming innocence after appeals have been exhausted, the work often falls to people on the fringe of the system, such as Risinger.

“The presumption is that if you are convicted, you are guilty,” says Barry J. Pollack, an experienced criminal defense litigator based in Washington, D.C., who has worked with Risinger and has significant experience with exonerations. “Courts don’t like to reopen old cases. It takes creativity and persistence.”

Freeing a person who has been tried, convicted and sent to prison requires the stamina of a long-distance runner. Attorneys face a marathon of paperwork and court battles, all necessary to persuade an overburdened criminal justice system to revisit a case that has been dealt with and closed. The work also requires the hide of a rhinoceros: The exoneration lawyer can expect resistance and, at times, outright hostility from the cops, prosecutors and defense lawyers whose competence or honesty is called into question.

Reinvestigation of closed cases requires not only persistence, but powers of persuasion far beyond the ordinary. Witnesses, who typically have nothing to gain and much to lose by cooperating, often have to be cajoled into re-testifying. “Lesley is incredibly tenacious,” says Kate Germond, director of Centurion Ministries, a Princeton-based exoneration initiative that deals with cases from around the United States and Canada.

Since announcing the Exoneration Project, Risinger has been swamped with more than 300 letters from New Jersey prisoners urging her to take up their causes. Their missives arrive at her small, windowless office in shoe boxes wrapped with duct tape, fat yellow business envelopes, or whatever packaging prisoners can lay their hands on. She patiently sifts through every one.

Risinger believes the Project’s first official (and to date, only) client, Kevin Baker, was the victim of overreaching by investigators and prosecutors, and of an inadequate defense. The man and woman Baker is in prison for murdering were the 13th and 14th people killed in Camden in the first month of 1995. The two were well liked in the community, and their deaths capped a crime spree that outraged the community and prompted street protests. Risinger contends that extensive media coverage put extraordinary pressure on the authorities to find the culprits quickly. Baker and another man, Sean Washington, were tried and convicted based on eyewitness testimony by a local woman. But Risinger says she can discredit the story told by the woman, who she asserts felt pressured to lie while being questioned by investigators for the prosecution. What’s more, she says she has found new evidence proving there was only one killer, not two, and that Baker was at his girlfriend’s apartment at the time of the slaying.

Risinger and her team have filed papers seeking a new trial based on their newfound evidence. Even if granted, a reversal is no slam dunk. Baker is no saint. He was previously convicted of aggravated assault. His posttrial challenges and appeals on the double homicide have been unsuccessful.

The case took a dramatic turn in September, when a key alibi witness died of breast cancer. For more than 18 months, Risinger had unsuccessfully pushed the court to order that bedside testimony be taken from the ailing woman. Baker says the woman, his former girlfriend, was with him at the time of the shooting. At the original trial, the woman appeared in the courthouse to testify, but was not called to the stand because of the defense lawyer’s concerns about a weakness in her story unearthed by the prosecution. Risinger—who says she can show that the concerns were unfounded—now will have to depend on statements the woman made to Baker’s previous defense attorney, as well as recent conversations she may have had with her sister.

Prosecutors are furious over Risinger’s accusations of malfeasance. “I have nothing nice to say about Lesley Risinger,” says Warren W. Faulk, the Camden County prosecutor. “She has made accusations about this office that are completely unjustified….I just don’t have time for someone who has made ad hominem attacks.”

Risinger pushes on, undaunted. She says she firmly believes in her client’s innocence. That alone, she says, makes every effort worthwhile. Ultimately, she sees herself fighting not just for Baker, but for all of New Jersey’s wrongfully convicted. “Our goal,” she says, “is to put ourselves out of business.”

Tara George is an associate professor of journalism at SUNY Purchase. She lives in Maplewood.