PAGE TWO OF FOUR

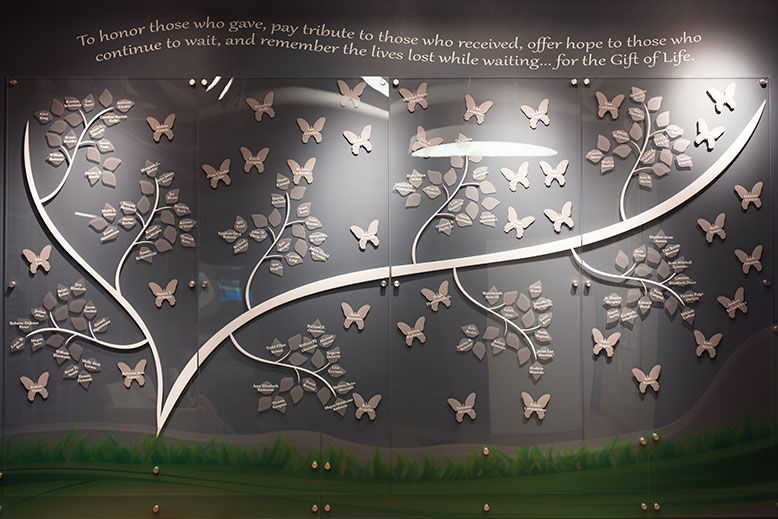

The Landscape of Life Wall is one of the many memorials in the Sharing Network building in New Providence where family and friends can visit. Photo by Allison Michael Orenstein

The organization functions much like a hospital and never closes. Staffers are on call 24/7. They respond to all 54 acute-care hospitals in the Sharing Network coverage area via emergency vehicles to evaluate patients, and they have HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) clearance to view medical records.

Under federal regulations, OPOs like the Sharing Network are the only agencies that can determine a patient’s suitability for donation, which they decide with the help of medical staff. Doctors, nurses and emergency personnel do not have the power to make that decision alone. Hospitals are required by law to contact an OPO every time there is a death or imminent death within their facility so they can respond appropriately.

“Time is of the essence when you’re talking about organs because different organs can stay out of the body for different periods of time,” Lue Raia says. “[Hospitals] have to call so that together we can assess the suitability of the patient for potential organ donor candidacy. That’s where our work starts.”

Once the call is received in the Sharing Network Donation Resource Center, a senior member of the transplant team will review the medical records received from the hospital staff and dispatch a small team, often consisting of a transplant coordinator, a hospital services manager and a member of the family-support staff.

This team is largely responsible for supporting the family emotionally and, in the early phases, coordinating with the Sharing Network on-site laboratory to run various tests to determine organ suitability and blood type and to identify any infectious diseases the patient may have.

The lengthy testing process is completed before the possibility of donation is presented to the family to avoid what is called a secondary loss—when a family approves of donation, only to find out their loved one isn’t eligible.

Sharing Network staffers like Oscar Colon and Paula Gutierrez (pictured with Judge F. Michael Giles) work on organ donation cases for up to 36 hours. Photo by Allison Michael Orenstein

In many cases, a patient’s organs are not accepted for donation. “A lot of these patients that we go see won’t actually become donors,” says Paula Gutierrez, hospital services manager with the Sharing Network. “They might be too sick, they might be experiencing organ failure, or some of them might just get better. It’s actually very rare that we end up speaking to the family about organ donation.”

The team also huddles with the medical staff on-site to determine how the family is handling the situation, what they have been told, and who is speaking for the family.

When it is determined that death has occurred or there is little to no hope for recovery, doctors will approach the family to share the news or make the declaration of death. The Sharing Network joins the medical staff to support the family and to discuss the option of donation.

Staff from the Sharing Network could be with a family continuously for as much as 36 hours as they await news of their loved one and contemplate donation.

“Every family is unique and every case is different,” Gutierrez says. “If there is resistance, it’s mostly because they’re still in shock and they’re dealing with loss, but most of them will sit there and think about it and say yes. And the kind of thing that moves me with what I do is being able to give the family something positive—it sounds weird, but it’s fulfilling to be that positive ray of light.”

Once the family has decided on donation, the medical management of the donor shifts from trying to keep the patient alive, to maintaining organ function up until procurement, or removal, of the organs. Transplant coordinators, most of whom have nursing degrees, run the ongoing tests, fill out paperwork and, in collaboration with a medical director from the Sharing Network, guide the on-site nursing staff in the steps needed to keep organs functioning properly until procurement.

At this time, tissue compatibility testing begins at the Sharing Network transplant laboratory to determine which of the patient’s organs are candidates for transplant and with whom the organs would be compatible. Various criteria must be met, and certain health conditions or treatments—like having had chemotherapy within the past five years—disqualify a patient from donating some, if not all, organs.

As organs are approved for donation, the transplant coordinator works with staff in the resource center to begin pulling up lists of potential recipients.

Computer algorithms are run through the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, which generates the best matches for each organ, factoring in blood type, tissue compatibility, the length of time the potential recipient has been waiting and how sick he or she is.

If the best match is in New Jersey, the team coordinates with the six transplant centers in the state, which are responsible for contacting waiting recipients. If a perfect match is found to be in another state, staffers prepare for the transport of that organ by car, plane or helicopter.

“When it comes to placement, we go locally, regionally and then nationally,” says Lue Raia. “But if there is a perfect match, that recipient will get top, top priority because we’re not only placing organs for transplant, we want to make sure as much as we can that the success rate of the transplant is as high as possible.”

Meanwhile, members of the Sharing Network stay with the grieving family as their loved one goes into surgery for organ recovery. They continue to update the family over several days on which organs were transplanted, who the recipients were, and the outcome of the transplantation.