“Why was I a drunk and a drug addict? I don’t think it’s a useful question,” David Carr says in a raspy voice that brings to mind a B-movie gangster. “Why did I get cancer? Why am I still alive? Why do I have a great job? Why did I recover and other friends of mine are dead? You can bend why whichever way you want. With or without the alcoholic gene, I think I got a pretty good break the day I was born.”

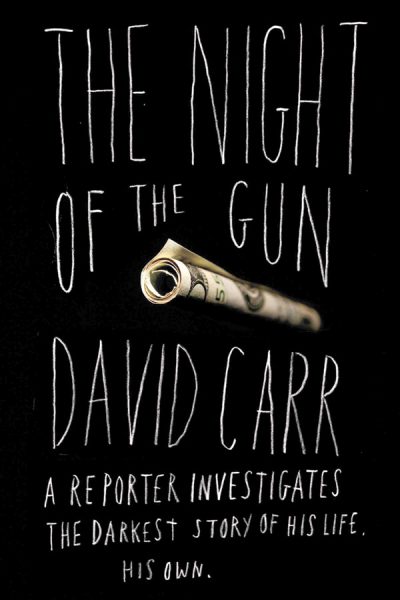

These days, that is hard to dispute. The 51-year-old Montclair resident, a media columnist and cultural reporter for the New York Times, is about to take his turn in the spotlight he has always craved. There have been other cravings, too, all described in Carr’s vivid guy-on-a-barstool voice in The Night of the Gun: A Reporter Investigates the Darkest Story of His Life. His Own. Simon & Schuster was impressed enough to fork over a $400,000 advance, the New York Times Magazine is running an excerpt, and a big movie deal may be in the offing.

Writing The Night of the Gun “was a little weird for me, because I’d always said I wouldn’t,” Carr says. For one thing, the story seems pure cliché: addict sinks to depravity, sees the light, enters rehab (five times!), lives happily ever after. (Except not quite—there are poignant twists, including a bout with Hodgkin’s lymphoma and, after fourteen years of sobriety, a relapse as a suburban drunk.) Also hard was mustering “the audacity of thinking that your life is that interesting. I never possessed it—I had to develop it.”

Sold in the wake of the controversy over James Frey’s substance-abuse confessional A Million Little Pieces (parts of which were revealed to be fictional), Carr’s book combines reportage with memoir. And why not? Memories lie, and the addict may be, as Carr suggests in the book, the ultimate unreliable narrator. As he puts it: “To be an addict is to be something of a cognitive acrobat. You spread versions of yourself around, giving each person the truth he or she needs—you need, actually—to keep them at remove. How, then, to reassemble that montage of deceit into a truthful past?”

The answer, he decided, was to fact-check his recollections. After all, reporting —not soul-searching—was what he was good at. “I’m not a particularly self-aware person,” he says with a trace of self-awareness. The fact-checking idea was also, he admits, “a gimmick,” a bit of “counter-programming” to help him sell the book.

We are talking on the screened porch of Carr’s “plain vanilla” 1920s white colonial in Montclair. A Minneapolis native, Carr moved here from Washington, D.C., in 2000 to work for Kurt Andersen’s short-lived digital-media news site, Inside.com. The house—where he lives with his wife, Jill Rooney Carr, 44, an event planner for Union Square Hospitality Group in New York; their 11-year-old daughter, Maddie; and a white Labrador, Charlie—has a lived-in feel.

There are photographs everywhere of Carr’s 20-year-old twins, Erin and Meagan, who are attending the University of Wisconsin and the University of Michigan, respectively. The living room is filled with a variety of work by local artists. The kitchen is spacious; Carr subscribes to Cook’s Illustrated and is equally at home at the grill or with a sauté pan. A framed copy of Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style, which Carr says blew out of the World Trade Center on the day of the 9/11 attacks, hangs in the dining room. Carr, not yet at the Times, covered the disaster for New York Magazine and the Atlantic Monthly.

Birds twitter in the backyard; the Lab tries to nuzzle me. Carr, looking haggard, is wearing Bermuda shorts and a black T-shirt. Having polished off edits to a Sunday story, he has been trying to finish his weekly column, “The Media Equation,” for the Monday business section.

Buttressed by photographs, legal and medical records, and old rejection letters from magazines, Carr set out to write about his life like an archaeologist exhuming the past. Not everyone was charmed. Carr says his first wife, Kim, responded, in essence “Enough with your drama.” Some potential sources—including his beloved sister, Coo, felled by an aneurysm—were no longer alive.

But many others cooperated, including Anna, the twins’ mother and, for years, Carr’s cocaine connection.

“Maybe I’m a really good reporter,” he says. “Maybe I’m an incredibly manipulative person.”

For more than two years, Carr (without taking a leave from the Times) conducted some 60 on-the-record interviews with people who had known him as desperate crack addict; hapless drug dealer; life-of-the-party drunk; kick-ass alternative press reporter; violent womanizing creep; and finally, redemptively, devoted father of twins born to a dope-dealer mother and almost lost to foster care. “Those were busy days,” he says wryly.

“Going back over my history,” he writes, “has been like crawling over broken glass in the dark. I hit women, scared children, assaulted strangers, and chronically lied and gamed to stay high.”

Even as a fledgling reporter in Minneapolis with investigative talent and flair, Carr was notorious. He was, he says, “loud and clanky, tough to miss. Guy covers city council in a bowling shirt and visor sunglasses, you’re going to notice him.” Swagger is still very much part of the Carr persona—“People don’t boss me around,” he says. But just as characteristic are Carr’s touch of self-deprecation and bracing humor.

“He’s a larger-than-life character,” says Sam Sifton, cultural news editor at the Times, who is Carr’s supervisor and friend. Sifton, another veteran of alternative newspapers, describes himself as a former Carr protégé. Carr, who made his mark as editor of the weekly Twin Cities Reader and the Washington City Paper, is “one of the last great charmers” and “an Irish storyteller of the old school,” says Sifton. “Even when you don’t know what he’s talking about, you’re riveted by it.”

Jill, Carr’s no-nonsense wife, says when they met through a mutual friend in Minneapolis it “literally was love at first sight,” even though neither was looking to marry. He was a divorced, single father of two. The candor of Carr’s memoir, which portrays her affectionately but mentions tensions between her and her stepchildren, “did not bother me,” she says.

Carr says he did not write the book for catharsis or to enlighten others. “I had girls going into college and I needed the money,” he says with typical frankness. “And media books don’t sell.”

Be that as it may, “David is a brutally honest person,” says Jill. “Anyone who knows him well knows this story. It’s not something he’s ever hid, which is one of his charms and gifts.”

After polishing off a late lunch, Carr, a diabetic, gives himself an insulin injection. Then he picks up an iced latte and smokes a cigarette. As I chauffeur him down the Parkway and Turnpike to Philadelphia, he chats, sips his drink, fields phone calls, plans the evening’s social activities, and, oh yes, furiously types. He files late, and, he says, sloppily, but, hey, it’s done—though there is still a PowerPoint presentation to prepare for his talk the next morning at the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies convention.

Carr, who writes and stars in hilarious videos every Oscar season for a popular Times blog called “The Carpetbagger,” can nevertheless be sardonic on the subject of bloggers. “They will not shut the f—- up,” he tells the AAN gathering. “I don’t care that your cat has leukemia! Stop typing! I’ll send your cat flowers!” He calls himself the Fred Flintstone of technology—more self-deprecation—but is planning an ambitious website for The Night of the Gun, including video excerpts of his interviews, built around the reveals that structure the book.

In many cases, he explains, “I thought things were one thing, and they turned out to be another. I thought [when] my children were born… I went right into treatment. That didn’t turn out to be true. I thought when I showed up at my lawyer’s that I was very much the presumptive custodial parent.” Also wrong. “I thought I was a pretty decent drug dealer,” but in fact, “I was a buffoon and I didn’t really even know it.”

The biggest reveal for readers may well be his description of his addict persona as “a fat thug” who battered his girlfriends. (He now is involved in efforts to combat domestic violence, a fact he omits from the book.) He describes the battering he inflicted as “fighting where one person clearly had the physical upper hand…. I could have walked away at any moment. What a male experiences as restraining is what females and police officers experience as assaultive.”

“I didn’t like writing that,” he stresses. “I’m not a violent person. I haven’t been in a fight in twenty years with anybody, let alone a woman.” But if “you start to shave that corner, the whole book sort of falls apart.”

“We all contain multitudes,” Carr says. “I’m still completely capable of being a thug if people push me in the wrong way—and I don’t mean assaulting them…. But I am nobody to f— with. And yet I’m a very gooey, sentimental father.” When Erin calls to say she’s finished the first 70 pages of the book, his parting words are, “I adore you!”

Carr, who plainly also adores the Times, says he worried that the book “was going to make me a problem at work, and so far that hasn’t been true. [Editor] Bill Keller was the first person at the paper to read it. He didn’t tell me he loved the book or anything like that. He just said he had no problem with it because it hews to the standards of my day job. It’s truthful, and as he said, ‘What are we supposed to do? Hire nuns?’ ”

A nun Carr is not, but it’s easy to detect the sweetness beneath the swagger.

“I tried not to tell any lies,” he says, “and I tried to not lie by omission. And, yes, it would make a tighter narrative arc if we got to that happy place where we all hugged, but that’s really not how life is. If readers end up responding to the book, that’s what they’re going to respond to—the authenticity of it, not the perfection of the story.”

Julia M. Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, is a contributing editor at the Columbia Journalism Review.