Ray Chambers does not claim to be the happiest man in the world, but he is acquainted with Google’s top pick for that distinction, the French Buddhist monk Matthieu Ricard. Chambers also happens to know what makes Ricard so off-the-charts happy.

“One of the things Ricard says is, ‘the most direct route to happiness is service to others,’” says Chambers, 76, New Jersey Monthly’s inaugural Catalyst Award honoree. The notably private philanthropist, renowned in Newark for putting his weight behind the city’s ongoing revitalization, and internationally for his commitment to eliminating malaria, reached the same conclusion decades ago.

Chambers, the son of a steel warehouse office manager, was born in Newark and graduated from the city’s West Side High School in 1960. In 1964, he earned a business degree at Rutgers-Newark and started a career as a tax accountant at Price Waterhouse, also in Newark. Seventeen years later, he partnered with William E. Simon, former U.S. secretary of the treasury, to launch Wesray Capital Corp., a private equity firm that made them piles of money in the 1980s.

But Chambers was having misgivings about his wealth. “I just knew that the expansion of my net worth wasn’t going to bring me fulfillment,” says Chambers.

So in 1989 he and his partners shut down Wesray, and Chambers put his money into trust. Since then, “I’ve been inartfully trying to improve the world,” he says from a conference room in the Morristown headquarters of his grant-making entity, MCJ Amelior Foundation. (The initials stand for the first names of his three children. He and wife, Patti, also have six grandchildren.)

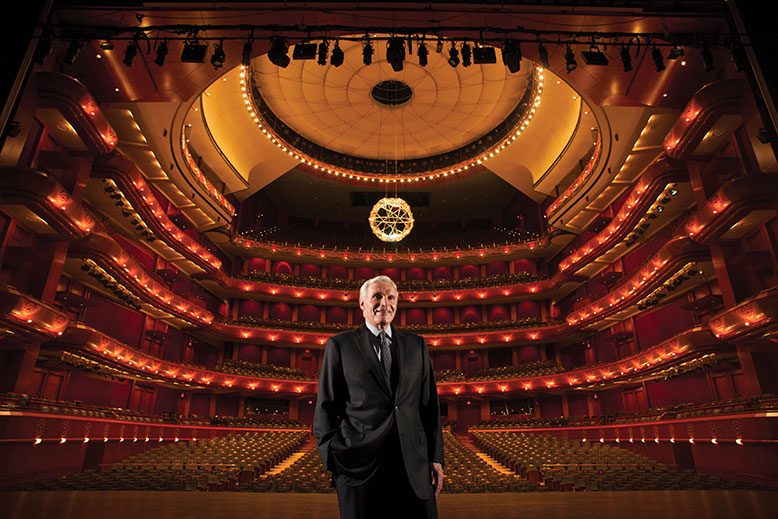

Playing ping-pong with kids at the Boys and Girls Clubs of Newark and funding college for 1,000 locals gave him liftoff. Bigger things were to follow. In 1997, he made a major gift to bring NJPAC to Newark and rallied his deep-pocketed colleagues to join him, essentially giving life to the state’s biggest arts center. To this day, he sits on the board of the Newark Alliance, the nonprofit dedicated to the city’s revitalization.

Sitting on the board is important, but Chambers prefers action. In August, for example, he brought attention to a situation at West Side High School that eventually found its way to the popular daytime TV show hosted by Ellen DeGeneres.

MCJ Amelior adopted West Side High 15 years ago—the foundation pays for many of the school’s programs. Two years ago, the principal, Akbar Cook, approached Chambers about what Chambers calls “an almost unbelievable” problem at the school. Teens were being bullied because their clothes were dirty. They didn’t have access to washer-dryers, and their caretakers couldn’t, or wouldn’t, help. Cook wanted to build a laundry room at the school for the kids to use.

“I encouraged Akbar to tell that story at an advisory committee dinner I host once a month,” Chambers says. “There wasn’t a dry eye when he was done.” (The PSEG Foundation eventually donated $20,000 for machines; the West Side High School Laundromat, in a former boys’ locker room, is now outfitted with five washers and five dryers.)

The machines were just the start of an outpouring. “Word got out and people started sending in gifts of supplies,” says Chambers. In early September, DeGeneres handed Cook a $50,000 check to buy supplies for West Side High.

Chambers has also been vocal, and visible, around efforts to get Amazon, one of the nation’s biggest retailers, to locate its second headquarters in Newark. “This quest for Amazon has been magnetic,” he says. “It’s brought everyone together—the private sector, the nonprofit sector.”

The identification of a common cause uplifts Chambers, especially when that cause matches his mission for advancing the greater good. President George H.W. Bush recognized that sensibility in 1990, when he appointed Chambers founding chairman of the Points of Light Foundation.

That post led, a decade later, to working with the United Nations to help achieve their Millennium Development Goals—near-impossible projects like cutting the world’s poverty rate in half, all meant to be achieved by 2015. The pursuit of those goals occasioned his encounter with the photograph that would change his life—and the lives of millions.

A colleague took the photo in Malawi, in Southeastern Africa, in 2005. In the photo, three children lay sleeping side by side. “I said, ‘Aren’t they cute?’ Then somebody pointed out that they were in malaria comas and probably died,” Chambers says.

Chambers went on to learn everything he could about malaria, including the jaw-dropping numbers of lives it claimed—more than half a million children in sub-Saharan Africa each year—and how it might be curbed by insecticide-treated bed nets. In February 2008, with Chambers’s plan to distribute the nets in place, the secretary-general of the United Nations appointed him the first special envoy for malaria. Now, because of Chambers’s efforts, more than a billion mosquito nets are in the hands of sub-Saharan Africans. According to UN figures, they have saved the lives of close to 7 million people, most of them children.

“It is by far the biggest thing I’ve done, and will ever do, in my life,” says Chambers. The rest of Chambers’s charitable work is also ambitious. In 2011, he founded the UN’s Global Health Alliance. Until earlier this year, he served as UN special envoy for malaria, and special envoy for health in Agenda 2030, the UN’s latest 15-year plan for improving the planet. Global gender equality is part of that agenda; Chambers is pushing for half the world’s nations to be led by women by 2030.

Parity for women, he explains, might make the world a happier place. “I’ve found…that the potential for happiness reaches its apex the more we recognize that we’re all the same, that we’re not superior or inferior to anyone else,” says Chambers. “When we put away those walls and lines of distinction and hierarchies, essentially it’s like helping ourselves…That’s why I’m addicted. That’s why I keep coming back.”