Lillian Kaplan Smith was just 2-1/2 years old in 1913, but she already had a sense of right and wrong. The little girl would walk to the jail on Main Street in Paterson with her mother and siblings to bring food to her father, imprisoned for taking part in the strike against the silk mills that broke out in February of that year.

Waiting outside the jail with her siblings while their mother delivered the food, Lillian could not hold her tongue. “Let my papa out,” she screamed. “He’s good. All the strikers are good.”

Telling her story seven decades later, Smith added that she didn’t stop wailing until her mother came out and “shushed me up.” [Smith’s recollections, and others in this story, were gathered as part of an unpublished history in the 1980s.]

Like many Paterson families, the Kaplans depended for their livelihood on the silk mills that gave Paterson its nickname, Silk City. But in 1913, some 24,000 Paterson workers walked off their jobs in a fight for better working conditions. During the strike, which stretched from February to July, 1,850 strikers were jailed and many of the nation’s best-known labor leaders came to the city to rally the workers. For Paterson’s 125,000 residents, it was a time of shared activism and sacrifice.

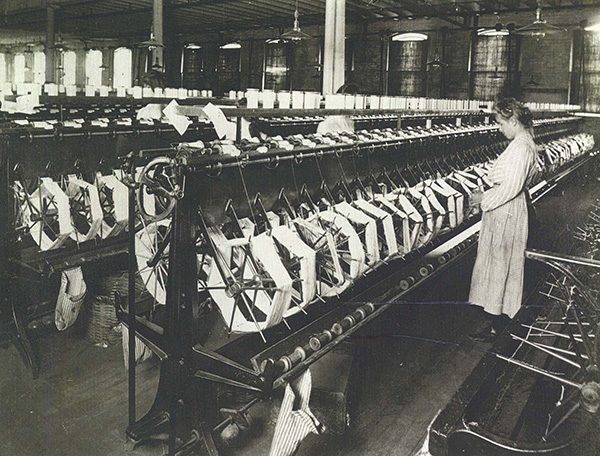

The epic struggle began in late January, when weavers from the Doherty Silk Mill rejected for the second time a four-loom system. The new system required each weaver to run four room-sized looms instead of two. To the already burdened workers, it seemed crushingly unfair. “The silk workers worked 55 hours a week, and children as young as nine worked,” says Haledon resident Bunny Kuiken, granddaughter of a striker. Moreover, Kuiken explains, the change to the four-loom system would eliminate some jobs.

Kuiken’s grandfather Pietro Botto was a skilled weaver, a craft he learned in his native Piedmont, Italy. His wife, Maria, did piecework at home in Haledon, the next town over from Paterson. As each of their four daughters—Olga, Albina, Adelia and Eva—turned 11 or 12, she joined other children in the mills. Maria helped meet the family budget by providing lunches for factory workers and taking in boarders.

Immigrant families like the Kaplans and the Bottos came to Paterson to work in the mills knowing little else of their new homeland. Elizabeth Bauer—whose father earned $12 per week as a picker (“He could spot one bad thread in a piece of silk and pick it out”)—recalled that her father twice sent money to pay for his family’s passage from Germany. Her mother, said Bauer, “did not want to come because [she believed] ‘there were Indians running around—they would scalp a white child.’”

In reality, 1913 Paterson was an “industrial boomtown,” wrote historian Robert Schoone-Jongen in the Passaic County Historical Society newsletter. Open six and sometimes seven days each week, the mills of Paterson produced silk that clothed Americans and lined their coffins. Those who ran the city’s approximately 300 mills and dye houses—men such as Henry Doherty and Catholina Lambert—were among the region’s wealthiest citizens.

While short-lived work stoppages were common, language barriers prevented workers from organizing on a large scale, said George Shea, whose grandfather, William Brueckmann, was mayor of Haledon in 1913. The Doherty mill protest might have flickered out if it had not been for the Industrial Workers of the World, a group founded in 1905 to promote worker solidarity. IWW activists “Big” Bill Haywood, Patrick L. Quinlan, Carlo Tresca and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn came to Paterson in February to unionize the mill workers, addressing them in at least six languages. That helped spread the Doherty strike to other mills. The Paterson Evening News reported in February that a general strike expanding the action to other industries was imminent. The workers’ key demands: an eight-hour day and improved working conditions, including a return to the two-loom system.

When Paterson police jailed picketers, the IWW held rallies across the city line in Haledon, where Mayor Brueckmann, a socialist, sympathized with their cause. The Botto family opened their 12-room home to the organizers and it quickly became a focal point for the movement. “None will return until all return,” IWW activists told workers, even as mill owners showed little sign of capitulation.

“People who saw these Haledon meetings never forgot them,” wrote the IWW’s Flynn. The rallies drew as many as 35,000 strikers to hear notables such as Upton Sinclair, the famed author of the 1906 novel The Jungle, speak from the balcony of the Botto home. Lillian Smith, who later lived in Fair Lawn, remembered the rallies. “It was very impressive for a little girl to participate,” she said, recalling singing and chanting alongside her father.

Initially, the strikers expected a quick resolution. “The first few weeks we lived high,” wrote striking millworker Joseph Steiger in his privately printed 1914 memoir. But as the stoppage dragged on, the strikers struggled to feed their families. Local papers reported that skilled dyers were working as pick-and-shovel laborers to earn money. Harry Barr, an immigrant from England who began millwork at age eight when his father fell ill, sold newspapers and delivered prescriptions. German immigrant Joseph Schofield’s father ran an IWW “relief store” on Ellison Street, where strikers came for handouts of food. Bakeries donated day-old bread and milkmen gave away spare milk, but families still went hungry.

The strike was particularly tough on the city’s youngest residents. Perhaps as many as 200 strikers’ children were sent to New York and elsewhere to stay with “strike mothers” who could better feed and care for them. But keeping track of the children added to the hardship of the strikers. “Frequently, men and women came to us half-crazed because they could not find their little ones,” wrote Steiger. Hearing of this, Paterson parents refused to send more children away.

To raise money for a relief fund, the IWW organized a pageant play at Madison Square Garden in June, reenacting key moments in the strike. Wealthy socialite Mabel Dodge and American socialist John Reed, the subject of the 1981 movie Reds, coached a cast of 1,029. Strikers played themselves, depicting police scuffles and a slain picketer. (Portions of the pageant were recreated in Reds.)

At the pageant, Steiger witnessed a group of performers, whom he described as “a mob of hungry Italians,” devouring a backstage meal as if they “had not seen anything like such a lunch for 18 weary weeks.”

“The thought flashed to my mind,” Steiger reflected, “if such fellows as these ever get the upper hand, they’ll make the French Revolution look like a Sunday school picnic.”

For all the rhetoric, zeal for the strike was ebbing. The pageant lost $2,000. By late May, some strikers crossed picket lines and returned to work. One by one, the silk mills began to spin again without significant concessions from the owners. In the end, Steiger wrote, the strike was “one of the most bitterly contested and wasteful contests in the history of the industries of this nation.”

Countless strikers were blacklisted. Some turned to working day to day for different Pennsylvania mills, a practice known as tramp twisting. Italian immigrant Attilio Azzie said that after the strike, his father, a skilled dyer, worked as a waiter, a handyman and a knife grinder. The strike “was a traumatic experience for my mother,” recalled Lillian Smith, explaining that it took years to reestablish the family financially.

Other families tried to forget the whole fiasco. Grace George, granddaughter of two striking weavers, said that in her family, the strike was never mentioned. “Two forbidden topics of conversation were the 1913 strike and World War I.”

Today, Paterson’s restored mills hum with artists and office workers. The Bottos’ 1908 Victorian home is now the American Labor Museum and a national landmark. At great cost, Paterson’s mill workers helped advance the 20th-century movement toward improved working conditions. “It had to be done,” Smith’s father told her decades after the strike. “It had to be done.”

Marcia Worth-Baker is a Paterson native who lived for a time in a silk worker’s former home.

MARKING THE CENTENNIAL

The American Labor Museum in Haledon is marking the 100th anniversary of the Paterson Silk Strike with a Centennial Commemoration. The exhibit, which runs through December 28, includes photographs, artifacts and original artwork depicting the people, places and events related to the historic months-long work stoppage.

The museum is located in the Botto House at 83 Norwood Street in Haledon. Hours of operation are Wednesday through Saturday, 1 to 4 pm and by appointment. For further information, visit labormuseum.net or call 973-595-7953.