Look up at a water tower on the Jersey Shore and, most likely, you’ll see the name of a beach town, a tourist slogan or a local attraction, such as Lucy the Elephant. On the southern end of Long Beach Island, the water tower reads Holgate, along with an image of what appears to be a modest beach house. Near the base of the tower along Barnegat Bay, the image becomes reality—a private house with a thin lookout tower.

That Holgate home shares a heritage with more than two dozen buildings along the Jersey coastline that are hidden in plain sight. They are former life-saving stations from the 1800s and early 1900s—essentially large boathouses built along the oceanfront. Upon seeing a ship in distress, locals would go to a station and wheel life-saving equipment and boats across the dunes to the water’s edge to rescue people from drowning and, if possible, save personal effects and cargo.

The Monmouth Beach station became a cultural center in 1999. Black-and white photo: Courtesy of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association; Color photo: R.C. Staab

Today, these stations have been renovated as private homes in Bay Head, Strathmere, Sea Bright, Spring Lake and Avalon, or repurposed for diverse uses such as a cultural center in Monmouth Beach, the meeting hall of the Kiwanis Club in Cape May and the tax office in Seaside Park.

All of these buildings, in one way or another, owe their existence to New Jersey physician William Newell, who witnessed a shipwreck and death of 13 crew members in 1839, not far from today’s Holgate water tower. When later he was elected to Congress, Newell was instrumental in securing funding in 1848 to create the United States Life-Saving Service to preserve “life and property” along America’s coastline. For more than 65 years, the Service built small boathouses, then larger life-saving stations, every few miles from Sandy Hook to Cape May. Despite the stormy waves of nor’easters and the pressures of real estate development, more than two dozen of these structures built between 1849 and 1915 have become part of the fabric of the Shore.

Remarkably, two such boathouses built more than 150 years ago survive.

In the shadow of the lighthouses at Twin Lights Historic Site in Highlands sits the last boathouse of its kind from the 1849-1850 era. After having been replaced by a newer structure in 1872, sold by the government to a local businessman to use as a horse stable, repurchased by the government in 1930 to refurbish as a museum, decommissioned by the government after World War II, and then finally given to the Borough of Highlands in 1956, the station was moved to the highest spot along the Jersey Shore overlooking its former home at Sandy Hook.

Today, visitors to Twin Lights can see the boathouse and its lifecar, an invention seemingly right out of a Jules Verne novel. In the mid-19th century, a rescuer on the beach would fire a line from a cannon-like gun to tie to the mast of a ship that was sinking or stranded. Then, the lifecar was hoisted onto the line and sent over the waves to the ship. Passengers and crew would climb into the car, lying beside or on top of each other, and then the car would be hauled safely back to the beach. It was first used at Squan Beach (Manasquan) to rescue passengers from the British ship Ayrshire and subsequently helped to rescue thousands of people.

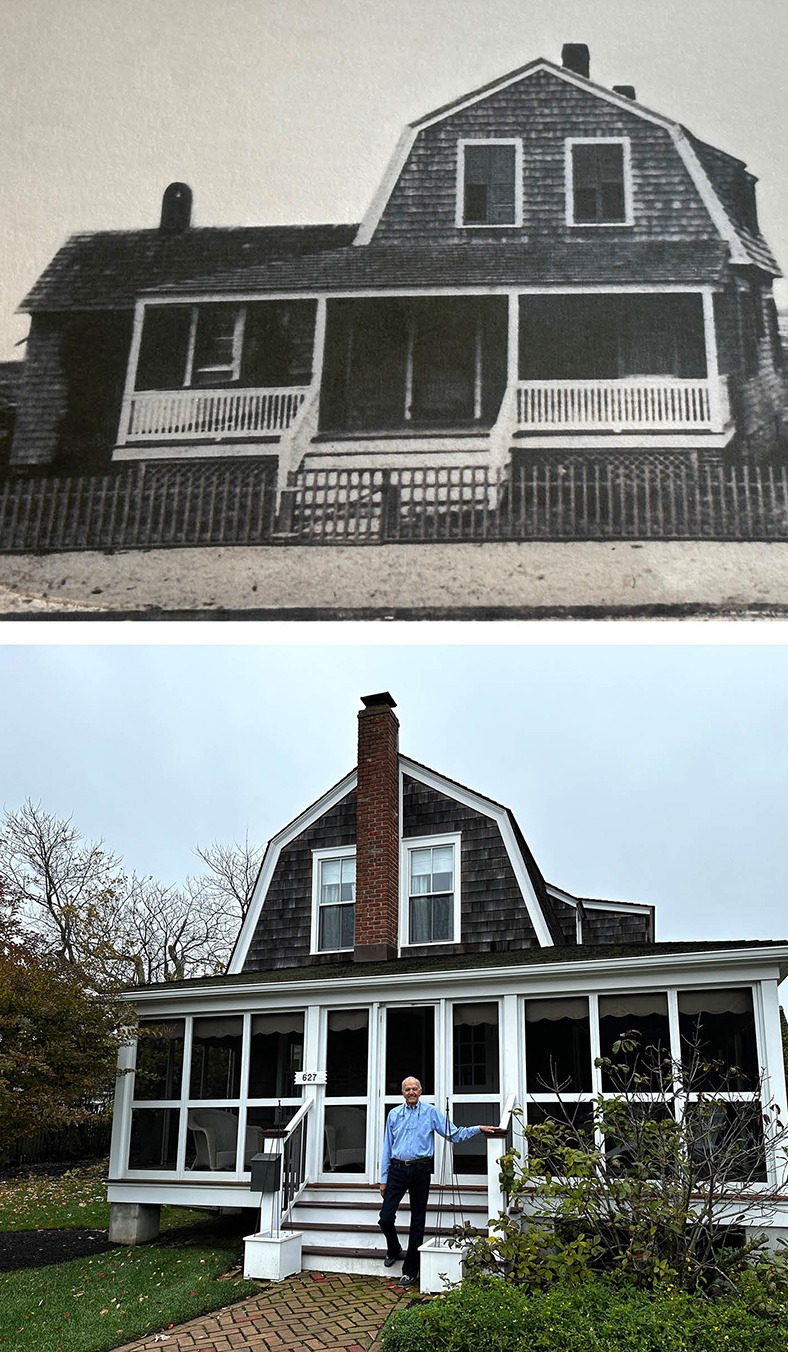

A former boathouse–turned–private home in Bay Head. Black-and white photo: Courtesy of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association; Color photo: R.C. Staab

Another interesting tale of a boathouse is told by John Beers, who owns a two-story Dutch colonial house in Bay Head. The front part of his home was originally a boathouse, built in 1871 in what was then Point Pleasant Beach. In 1871, Elijah Chadwick, a local fisherman and farmer, bought it.

“Of all the buildings that the Life-Saving Service built, 99 out of 100 were purposely designed to move. They would jack them up and move them to prevent damage from sea encroachment,” explains Tim Dring, past president of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association and a retired Navy commander.

That was what Chadwick did, moving the house one block west to Main Avenue. He replaced the pitched roof with a Dutch colonial to make a comfortable home at the sparsely populated beach. When Lake Avenue was created, he moved the house one last time, to a quieter street near the bay.

Years went by as rooms were added under different owners. In 1982, Beers and his wife, Gail, purchased the property. As Beers says, it would have been a prime candidate for a McMansion because it sits on a double lot. But Beers says that the town historian “almost made me swear that I wouldn’t muck up the house and tear it down.” The family kept the historic parts of the house intact, adding a new kitchen, family room and second-floor addition in the back.

[RELATED: Inside the Jersey Shore’s Unique Community of Tiny Houses]

Though the life-saving stations were initially successful, Dring says federal support was sporadic, there weren’t trained crews, and eventually “the stations were broken into and the equipment pilfered.” By the end of the Civil War, the federal system had fallen into disrepair. In 1871, the Treasury Department convinced Congress to increase spending to hire full-time staff and build new stations that could accommodate larger boats, more equipment, staff lodging, and rooms for rescued people who needed a place to stay before continuing their journeys.

The stations that the government built, rebuilt, remodeled and moved along the Shore from 1871 to 1915 have inspired Shore architects for more than 100 years. The turrets, lookout towers, peaked roofs and dormer windows of the Life-Saving Service era are now such a part of Shore style that, in some beach towns, it’s easy to mistake a recently constructed home for a restored life-saving station.

After 1915, the Life-Saving Service was merged with the Revenue Cutter Service and became the United States Coast Guard, which eventually had little use for these stations, except for the Townsend Inlet station in Sea Isle City, which the Coast Guard still uses as a recreational facility. Why would the Coast Guard decommission or abandon prime beachfront property? Dring says the advent of steel ships with powerful engines and an increasing focus on recreational boating accidents steered the Guard away from the beachfront to locations on inlets and rivers where they could directly launch into the water.

Each remaining station took a different route to its present use.

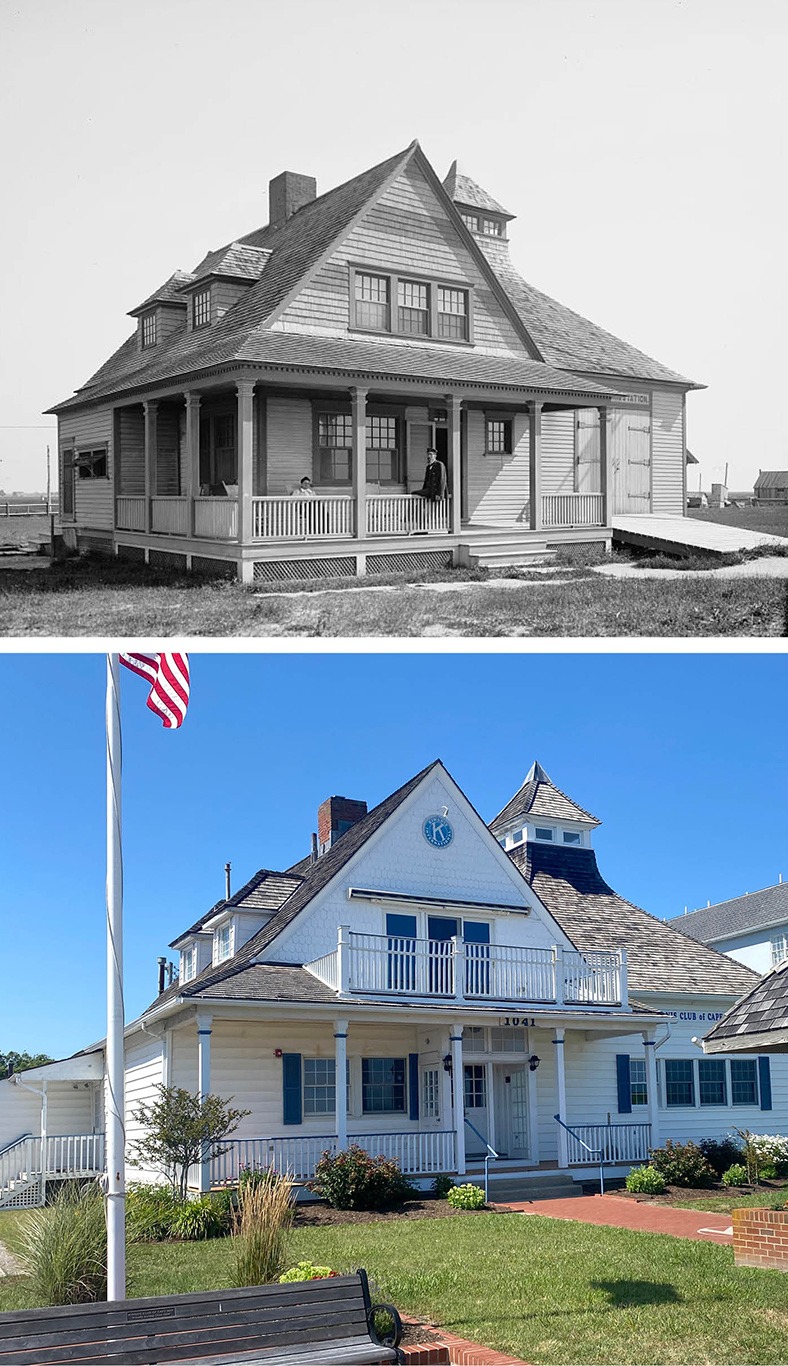

The former Cold Springs Station is now the meeting space for the Kiwanis Club in Cape May. Black-and white photo: Courtesy of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association; Color photo: R.C. Staab

Imagine paying $120 (or $2,600 in today’s money) in Cape May for a building across from the ocean, where today there are million-dollar Victorian homes and hotels. In 1939, that’s what the Kiwanis Club paid for the Cold Springs Station along Beach Avenue in an auction of decommissioned federal property. “There was a Coast Guard officer who had been at Cape May station who had been very friendly with the Kiwanis guys. He was transferred to New York Fourth Naval District,” Cape May Kiwanis member and former mayor Robert “Bob” Elwell explains. With a wink and a chuckle, Elwell says, “He happened to be the guy who opened the bids. And so it turned out that the Kiwanis Club bid was a few dollars higher than the highest other bid!”

Throughout the world, most Kiwanis Clubs meet in restaurants. But in Cape May, meetings at the clubhouse are often followed by lively card games upstairs, following in the tradition of surfmen who used the space as their bunkroom.

Farther up the Shore, in Stone Harbor, American Legion Post 331 and its Auxiliary were meeting in the Borough Hall and in firehouses. In 1948, when the Coast Guard deactivated what had been a life-saving station at the southern tip of Seven Mile Island, the legionnaires and auxiliary bought the building, plus its two-lot property, for $2,539. The men and women of Post 331 have enthusiastically embraced the history of the building, restoring its exterior. The building is open for free tours from Flag Day to Labor Day. In addition to a military museum on the second floor, visitors can climb to the lookout tower for remarkable views.

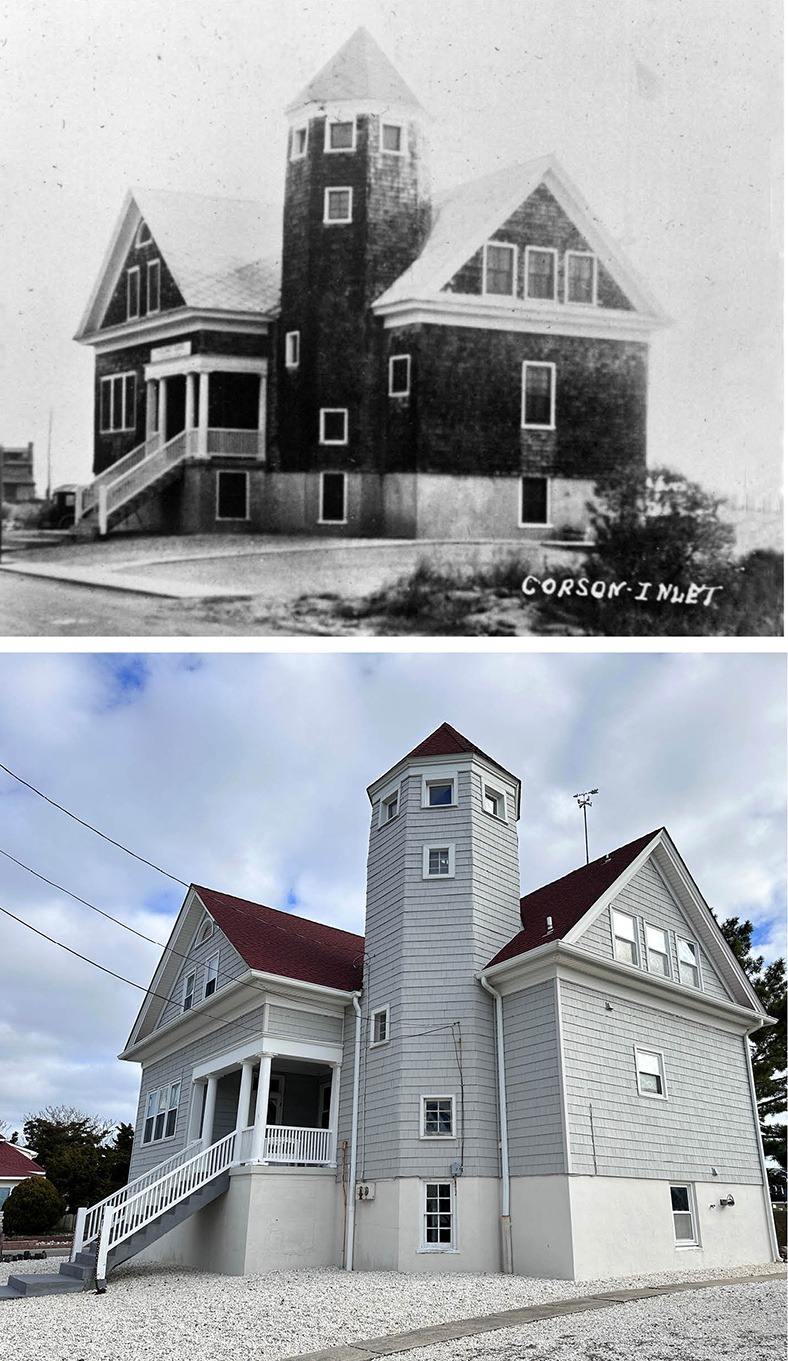

This private home, originally built in southern Ocean City, was dismantled in 1924 and rebuilt in Strathmere. Black-and white photo: Courtesy of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association; Color photo: R.C. Staab

It’s not only social organizations that were able to buy stations. Stephen and Wendy Bell have a home in Strathmere that served as a station on an island farther north. The station, built in 1872 in southern Ocean City, was imperiled by shifting sands and storms. So, in 1924, the Coast Guard dismantled it, put it on a barge to cross Corson’s Inlet, and rebuilt it on Bayview Drive in Strathmere. In a more protected space and with a new boathouse across the street along the bay, the Coast Guard used it until 1964.

The Bells took care to restore the property after buying the house in 1994. The couple and their four children use the house as a summer home that, when stretched to capacity, can sleep 14 people. A special guest feature of the house is the queen size bed in the lookout tower, a room they’ve dubbed the honeymoon suite.

“In the summer, people often walk down the street and ask questions,” Bell says. “Sometimes, to my wife’s disdain, I invite them inside!”

Communities have united to help save stations. With the threat of a wrecking ball looming in 1999, local residents banded together to save the Monmouth Beach station and turn it into a cultural center. In Seaside Park, the borough purchased the building in 1966 and then, 30 years later, moved borough offices into the newly restored building. At Island Beach State Park, the state created an interpretive center in part of one old station, while in another section of the park, a former life-saving station serves as a maintenance facility, visible from the road near the entrance.

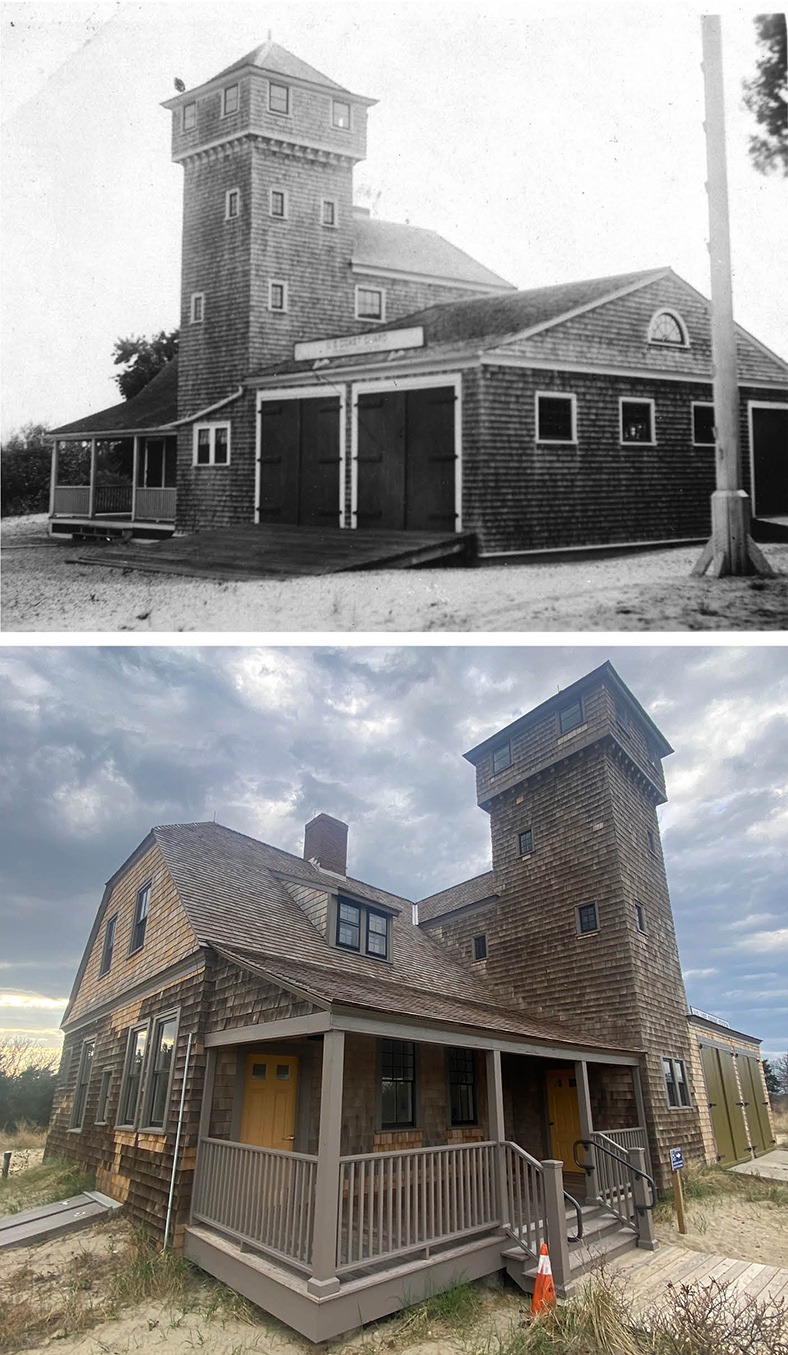

The Spermaceti Cove station in Sandy Hook National Park, built in 1894, recently underwent an exterior renovation. Black-and white photo: Courtesy of the U.S. Life-Saving Service Heritage Association; Color photo: R.C. Staab

Another branch of the federal government has also joined the effort. In Sandy Hook National Park, the Spermaceti Cove station, built in 1894, survived several government transfers, as well as Hurricane Sandy. The exterior was recently renovated by the park service in a near picture-perfect setting atop a dune overlooking the ocean. One can easily imagine a turn-of-the-century station keeper in the tower searching the New York Bay and the Atlantic Ocean for ships in distress.

In many ways, the history of the U.S. Life-Saving Service has been eclipsed by the life-saving efforts of the U.S. Coast Guard and its fleet of modern, mechanized boats. Yet two restored stations are keeping the memory of the Service alive.

In Manasquan, Ron Jacobsen, president of the Squan Beach Life-Saving Station Preservation Committee, describes former Station No. 9 as “the most beautiful historic structure in New Jersey.” Although the town bought the building for just $1 in 2000, the town and the committee have spent hundreds of thousands of dollars removing asbestos, redoing the plumbing, replacing shingles covered with lead, and collecting and displaying artifacts. The station is open May through September. Admission is free.

For the most colorful and historic look at life in a station between 1885 and 1905, visit U.S. Life Saving Station 30 in Ocean City. “When you come in the building, you are living the way men lived during the Life Service,” says its president, John Loeper. “You’re seeing what they saw day to day.”

The boathouse section of the building features a 26-foot surfboat, life-saving equipment, and even gear that the men used for hunting and fishing. Recreated rooms include the station keeper’s office, kitchen, dining room, and an upstairs bunk room with a ladder to the lookout tower.

The keepers of Station 30’s history are doing a deep dive into the individual histories of the 65 men who worked there, rescued people from shipwrecks, and were buried nearby. They are giving life to the history of a service that, in 60 years, with non-motorized boats and equipment, helped to save more than 186,000 people from treacherous waters around New Jersey.

Beyond the life-and-death stories of survivors, Loeper tells the story of the service’s other mission: to protect cargo: “There was a produce ship sailing up the coast full of watermelons that got in trouble at a sandbar. The captain said ‘lighten the loads,’ so the crew threw the watermelons overboard.” The ship safely docked, but the life-saving crew, not the ship’s, had one more task. Loeper says, “They spent two or three days rowing the inlet to save the watermelons and return them safely to the ship in Somers Point.”

R.C. Staab writes extensively about the Jersey Shore, including the book 100 Things to Do at the Jersey Shore. In the summer, he runs, swims, kayaks and walks the beaches from Sandy Hook to Cape May.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.