It’s been 87 years since the state of New Jersey executed an unemployed German immigrant from the Bronx for kidnapping and killing famous aviator Charles Lindbergh’s 20-month-old son.

Bruno Richard Hauptmann’s trip to the electric chair on April 3, 1936 followed one of the biggest criminal investigations in American history: It generated more than 200,000 documents and pieces of evidence, including hand-written ransom notes, pieces of wood from Hauptmann’s attic and a homemade ladder that police said was used to snatch Charles Jr. from his second-floor nursery at Lindbergh’s home in the Sourland hills outside Hopewell.

All of that evidence remains in storage at the New Jersey State Police headquarters in West Trenton. The archive and a modest museum attached to it have become holy ground for a small but fervent army of researchers, writers and kidnapping hobbyists. They’ve spent years elaborating on revisionist theories about the boy’s murder and insisting that the state subject the evidence to modern-day forensic testing that might show, for example, that Hauptman did not act alone.

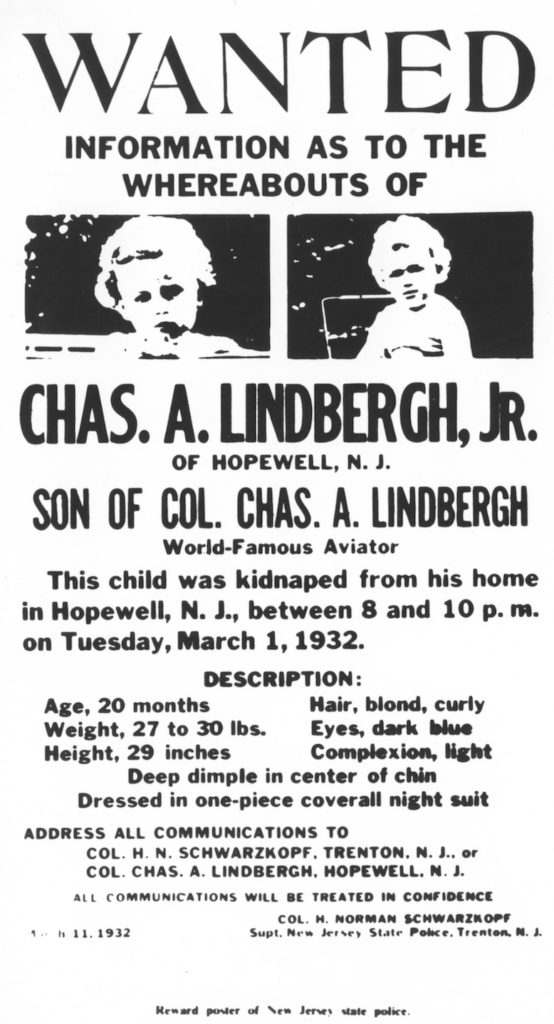

A 1932 wanted poster seeks information about the kidnapping of Charles A. Lindbergh Jr. Photo: Photofest

Late last year, Margaret Sudhakar, a freelance researcher from Princeton, filed a Superior Court lawsuit demanding the state release samples of some evidence for DNA analysis and other lab tests. In court filings, Sudhakar said she had spent years researching the case and had volunteered at the museum for a decade, befriending its chief archivist, Mark W. Falzini.

Sudhakar has been working with a Los Angeles-based filmmaker since 2015 and says she has assembled a team of 30 experts to analyze the evidence, including pediatric neurosurgeons, forensic pathologists, medical examiners and DNA experts.

“The time for speculation about the New Jersey State Police’s most famous case is over,’’ Sudhakar wrote to the court. “The time for answers is upon us. The answers to the most basic questions of this case, including who sealed the envelopes, who licked the stamps and who made the ladder, can all be obtained with modern day forensics at no cost to the state of New Jersey.’’

New Jersey Monthly can reveal that in January, Judge Robert Lougy dismissed Sudhakar’s claim, ruling that the researcher had no legitimate right to take evidence for analysis that could permanently alter it, even if the evidence belonged to the public. The state’s open record law, Lougy wrote, “is not the vehicle by which a citizen can march up to a museum and demand that the custodians of historical artifacts and documents surrender the state’s treasures for analysis, alteration and destruction.’’

Sudhakar’s lawyer, Kurt W. Perhach, declined to comment on the ruling and said his client was unavailable for comment. But he said they were considering an appeal to Lougy’s ruling. Perhach, who took on Sudhakar’s case pro bono, is a kidnapping buff himself who said his fascination with the case initially sparked his interest in the law.

Despite winning this round, the state will certainly face mounting pressure to subject the Lindbergh evidence to the kinds of high-tech lab analysis that did not exist in the mid-1930s. In recent years, there has been a raft of new books, including a multi-volume set over 1,000 pages long, exploring every possible angle of the kidnapping case. A trio of Lindbergh internet blogs and discussion forums draw millions of hits every year.

In her suit, Sudhakar recounted comments from a state police official who told her it was long past time for critical evidence, such as the ransom notes and kidnapping ladder, to be released for scientific testing.

“The questions will keep coming because the full story isn’t out there,’’ Perhach says.

The State Police did not respond to written questions submitted by New Jersey Monthly about its handling of the Lindbergh evidence and unwillingness to release material for tests using current forensic technology.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.