Illustration: James Steinberg

The recent advent of injectable drugs to treat diabetes and obesity has rocked the medical community, making it possible to treat once intractable health issues. But their rising popularity—and media attention, with celebrities being called out for using Ozempic to keep their figures trim—come with growing controversy over ethics, cost and access.

Designed to treat type 2 diabetes, Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro have been nothing less than life-changing for diabetes patients who previously had few options besides insulin and grueling dieting. For doctors, the injectables have opened the door to new treatment possibilities, fulfilling their hopes of promoting health and alleviating pain and suffering.

“I’m excited for my patients,” says Dr. Stephen Sherry, an endocrinologist practicing in Essex County. “Because of these medications, the number of patients who have been able to get their diabetes under control is enormous.”

Though these medications were initially designed to treat patients with type 2 diabetes, many physicians believe, as Sherry does, that people battling serious weight issues should have equal access to them.

“Yes, diabetes is a dangerous disease. But obesity is also a dangerous disease,” says Sherry. “So who should be allowed access to medication? That’s a tough one. Now we’re talking about rationing drugs. Would I prescribe it to—pick your Hollywood starlet, 6 foot tall, 128 pounds, who thinks they’re overweight? No. But that’s not what we’re talking about. We’re talking about people that meet the criteria for treatment.”

These drugs are designed to mimic the way a healthy pancreas releases insulin into the body. Known as semaglutides or GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1), they work similarly to aid insulin production while suppressing hunger messages to the brain. The Danish multinational pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk (which has its U.S. headquarters in Plainsboro) developed Ozempic and Wegovy, while American pharmaceutical giant Eli Lilly manufactures Mounjaro.

HIGH PRICE OF CARE

The ethical question of who is entitled to these drugs is only part of the debate. Right now, in many cases, insurance companies will cover them for patients suffering from type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetes, but not obesity. These injectables are not covered by Medicare either, except to treat diabetes.

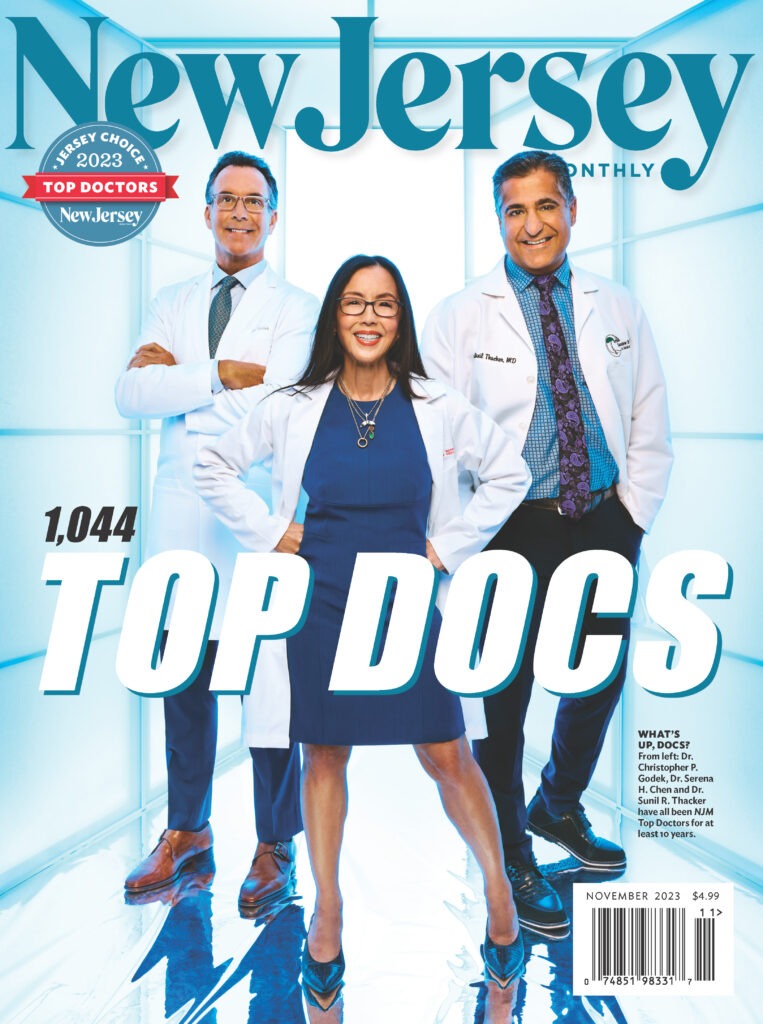

Buy our November 2023 issue here. Cover photo: Brad Trent

So patients who want to use one of these medications to treat obesity, but can’t afford to pay $1,000 or more per month out of pocket, likely can’t access the drugs. This situation creates an unfortunate dilemma: Wealthier people, who tend to have lower rates of obesity, can afford the injectables, while poorer people, who tend to have higher rates of obesity, cannot.

Some health practitioners disagree with the assessment by some insurers that obesity is a vanity issue. Serious health issues coexist with obesity, such as coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, stroke, osteoarthritis, cancer and, of course, type 2 diabetes. These are covered by insurance.

“So we do prescribe these medications when appropriate, for weight loss,” says Dr. Anna Kissin, a physician at Endocrine Consultants of Morris County in Florham Park, citing the risk factors of obesity. “Of course, if a patient comes in and they just want to lose, you know, 5 or 10 pounds before vacation, that’s not a reason to prescribe these medications.”

In fact, there is growing empirical evidence that obesity is caused by a complex mix of biology, heredity and lifestyle. In recent years, medical researchers have identified more than 1,000 genes and variants that increase a person’s risk of obesity. (At a 2022 global health-leaders conference on obesity, the participants concluded there was “no consensus whatsoever about what the cause of it is.”)

Lifestyle can, and often does, contribute to obesity, but doctors say assigning blame is not the point—treating the patient is.

“If you’re obese, if you’re diabetic, your pancreas can’t make enough insulin for your needs—that process is a steady decline that’s not typically going to get better,” says Sherry. “Let’s say in conjunction with Ozempic, you also start to exercise significantly, and you stop eating Twinkies and drinking Coca-Cola. Then, maybe you lose the weight. But you know, it’s a complicated thing. You have to change your relationship with food.”

[RELATED: New Jersey’s Top Doctors]

That is exactly what Ozempic, Wegovy and Mounjaro help patients do. “These medications help patients break destructive cycles and allow them to start losing weight,” notes Kissin. “They eat less and then hopefully, they lose weight. They can then become more active and start a regular exercise regimen.” She adds, “What’s frustrating is when patients come to us for help, and their insurance company won’t cover the medications. Without insurance, the cost is prohibitive for most people.”

SEEKING SOLUTIONS

Desperate for a solution to unhealthy weight gain, some people without insurance are seeking alternative ways to get the medications. A quick internet search for Ozempic can spark a flurry of ads displaying an injectable drug resembling the blue Ozempic pen.

Kissin says, “We’ve heard from some patients, and also from the reps that come in from these drug companies, that there are these compounding pharmacies that make what they’re calling semaglutide and tirzepatide. Patients are injecting it themselves. We don’t really know what it is they’re injecting, but we know it’s not the real medication.”

Kissin, who calls insurance companies’ refusal to pay for the medications “the biggest hurdle my patients face,” says the drugs made at compounding pharmacies are often sold at popular health and beauty establishments know as medi-spas.

[RELATED: NJ Medical Schools and Residency Programs Are Now Teaching Compassionate Care]

“At medi-spas, they sell what they call semaglutide tirzepatide in vials,” she says. “The proprietary recipe for these medications is owned by the companies that make Ozempic and Mounjaro. But you don’t know what’s in them, really—people don’t know what they’re injecting.”

Sherry says if a physician prescribes a GLP-1 medication for a patient, Medicare can’t cover it because the national insurance system is forbidden by law from covering obesity drugs.

He notes, “Municipal and state employees in New Jersey, teachers included, are far more likely to have coverage for obesity drugs than many other insurers, although they’re starting to catch up [with the trend of insurers refusing coverage].”

He adds, “I was the diabetes director for an insurance company in the past, and basically their stance is, ‘We need short-term payback.’”

WIDESPREAD ISSUE

Obesity currently affects more than 40 percent of adult Americans and costs the U.S. health system about $173 billion each year. An analysis published in the New England Journal of Medicine in March 2023 found that, if all obese Medicare beneficiaries were prescribed semaglutide, the cost would be nearly double the entire budget for Medicare prescription drugs.

On a positive note, the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped the cost of insulin to $35 and will help lessen the cost of other weight-loss drugs. However, this won’t happen until 2027 for Ozempic and Wegovy, and until 2031 for Mounjaro, according to a Medicare Policy report.

In New Jersey, 9.4 percent of the adult population currently have diagnosed diabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). An additional 207,000 people in New Jersey are estimated to have diabetes without knowing it, and 2,395,000 people in New Jersey, or 34 percent of the adult population, have pre-diabetes (blood glucose levels that are higher than normal, but not yet high enough to be diagnosed as diabetes).

The CDC notes that medical expenses for people with diabetes are approximately 2.3 times higher than for those who do not have diabetes.

Ginine Cilenti, executive director of the Diabetes Foundation in Mahwah, admits that money and medication are important factors in controlling the progression of diabetes. But patients and doctors have other tools available to them to improve health outcomes.

“We are all about education at Diabetes Foundation,” Cilenti says. “Education can bring your A1C (a measurement of blood sugar levels) down by, like, one to two points. In this way, it’s just as effective as some medications.”

Cilenti defines education as “understanding how to problem-solve when your blood sugar goes up or down, how to reduce risks, which doctors to go to, what immunizations you need. Also, understanding what a difference physical activity and healthy eating makes in your life.”

Cilenti and her team at the Diabetes Foundation work to help patients navigate the practical and emotional issues related to their condition. Unlike the American Diabetes Association (ADA), which works on research and advocacy (for instance, lowering insulin costs), the Diabetes Foundation operates on the ground level, working directly with food pantries, health systems and patients themselves.

“Our focus is more on the day-to-day tangible tools that people need to manage their care,” Cilenti says. “We provide transportation, take people to doctor’s appointments. We offer free education, free social support programs. Some people have been with us for five years in our social support groups. It just makes them feel good. They don’t have social support anywhere else.”

She added, “We’ve definitely seen an increase in people asking for help to find injectables—as you know, there’s a limited supply on the market. We provide assistance for this, to the extent that we can. A lot of the individuals we serve don’t use those kinds of medications, because they can’t afford them at all.”

While the rise of diabetes and obesity throughout New Jersey and the United States is concerning, these groundbreaking new medications (with more in development), combined with increased public awareness and recent federal caps on insulin costs, give doctors and patients hope for the future.

As Sherry put it, “There are 31 million type-2 diabetics in the United States, 80-85 percent of them are obese or overweight, and yet, here we have the first safe and effective treatment that causes significant weight loss and can reverse diabetes. We didn’t have much in that universe before.”

Linda Federico-Ó Murchú is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in outlets including NBC News, CNBC, the Today show and TheStreet.com. A Montclair resident, she is currently working on three books.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.