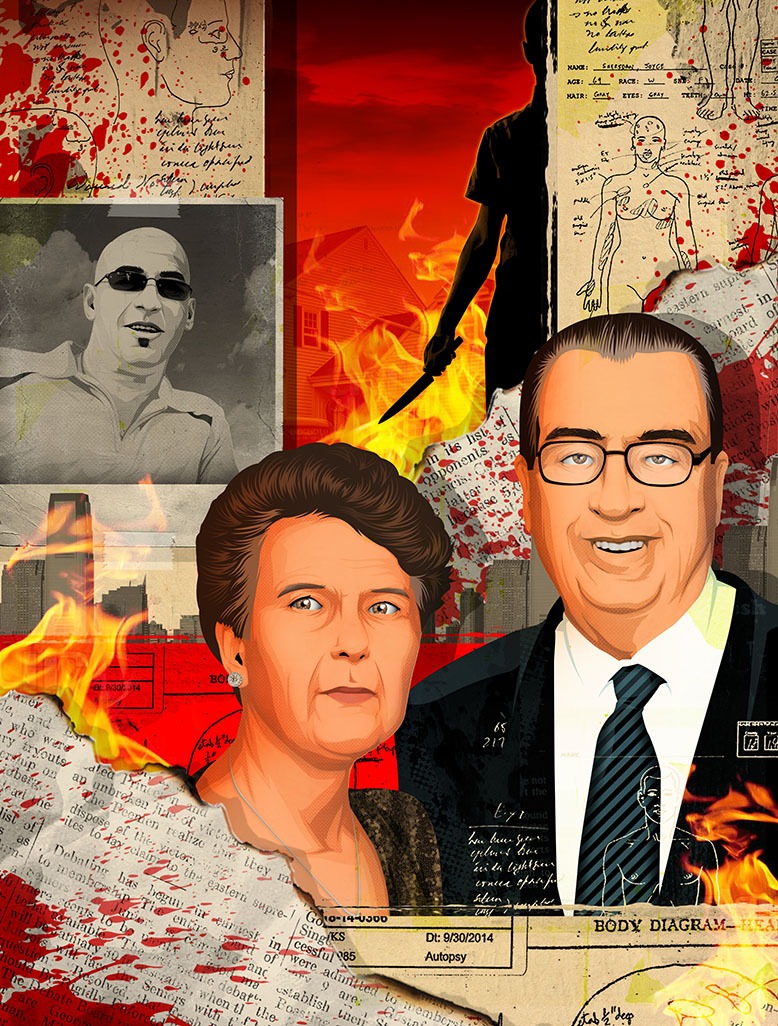

Illustration by Taylor Callery

Mark Sheridan, a prominent New Jersey lawyer, was reading the newspaper one morning this past January when an article about an unsolved, 8-year-old murder caught his eye. The story was about Sean Caddle, a little-known Democratic operative from Jersey City who was appearing in federal court to admit that he’d paid a Mob-connected hit man to kill Michael Galdieri, a friend and colleague who also worked the North Jersey political circuit.

But Sheridan really sat up and took notice when he came to the description of how Galdieri had died—he’d been stabbed multiple times in his Jersey City apartment by a home invader who then proceeded to set the scene on fire.

Practically the same gruesome thing had happened to his own parents, John and Joyce Sheridan, who had been found stabbed to death in a burning bedroom of their home just north of Princeton on September 28, 2014—just four months after Galdieri was killed.

John Sheridan was a health care CEO and former cabinet officer in Trenton, where governors of both parties had sought out his skills as a lawyer and legislative expert.

The Sheridan deaths, like the murder of Galdieri, had gone unsolved for years—although they had originally been designated a murder-suicide by authorities, that was later reversed, and the cause was listed as undetermined.

There was more. The hit man responsible for killing Galdieri was arrested in Connecticut on September 30, 2014, just about 24 hours after Sheridan‘s parents’ bodies had been found. The lead hit man, George Bratsenis, a career criminal and Mafia enforcer, was carrying rubber gloves, a homemade mask and a long-handled kitchen knife in his car when police pulled him over.

It just so happened that a long-handled kitchen knife was also missing from the kitchen of John and Joyce Sheridan’s house, where it had been stored in a block by a rear door that any intruder would have passed. The sharp weapon that medical examiners said had been used to slice into John’s jugular and kill him had never been found.

Could it possibly be a match for the hit man’s knife?

STRIKING SIMILARITIES

A soft-spoken corporate attorney, Mark Sheridan is a commercial litigator by trade who also worked for many years as general counsel for the New Jersey State Republican Committee. He speaks in measured, analytical paragraphs. He does not excite easily and is not given to exaggeration.

Soon after reading about Bratsenis and his kitchen knife, Sheridan dashed off a letter to the state Attorney General’s Office asking that the investigation of his parents’ deaths be reopened in light of what he described as the “eerily similar” circumstances surrounding the murder of Michael Galdieri.

“You’d have to be blind not to see the similarities,’’ Sheridan said in a recent interview with New Jersey Monthly.

Sheridan says he never heard back from the attorney general. But on May 31 of this year, the office of acting attorney general Matt Platkin confirmed that they were indeed taking another look at the Sheridan case.

Platkin’s decision may have been prompted by a series of podcasts produced by WNYC Public Radio that revisited the Sheridan deaths and raised troubling questions about an allegedly botched investigation and other issues.

“At this point, after all this time, I’m not sure what can be uncovered by a new investigation. But I’m grateful to know somebody is finally making an attempt to set the record right,’’ Sheridan tells us. “There are so many questions. Who knows where it might go?’’

Federal agents, meanwhile, continue to work with Caddle in what they have cryptically termed “a major investigation.” Even after admitting to arranging Galdieri’s murder, Caddle remains out of prison in the relative comfort of home confinement, wearing not shackles, but an ankle monitor. Prosecutors, who have postponed his sentencing for months, say Caddle isn’t a flight risk.

So now, with investigators digging again into the Sheridan case and continuing to press Caddle, the state is awash in intrigue about what comes next. What secrets might ooze out as investigators probe the deaths of two men who made careers in the rough-and-tumble world of Jersey politics?

In and out of Trenton, elected officials, lobbyists, and everyone else who is part of that political world have been waiting anxiously for some other shoe to drop. Just where and when it might fall, and on whom, makes for the kind of parlor game played here since Jimmy Hoffa’s body was allegedly dumped in the Meadowlands.

The cases are in many respects parallel mysteries: Both John Sheridan and Michael Galdieri died amid fire in late-night scenes of extraordinary violence.

Both men had tussled with powerful political forces and may have paid a price for it.

The only reason for his parents’ deaths that Sheridan could come up with was that someone killed them.

A CONTROVERSIAL FIGURE

Galdieri was a college dropout who played bit parts for the Hudson County Democratic machine. He’d been arrested on drug charges and spent two years in prison before going to work for Caddle, a political consultant who allegedly created a string of dark-money political funds. At the end, he was living alone in a tiny second-floor apartment over a barber shop in the west end of Jersey City.

His political struggles began in 2005, when he decided to run for Jersey City Council, a move that put him in direct conflict with a Hudson County Democratic machine that had strict control over elections and public jobs.

During the campaign, Galdieri threatened to expose wrongdoing inside city government, including what he alleged to be ongoing corruption in the Jersey City water-supply agency. In a public debate held before the election, Galdieri announced that he would hold a press conference and identify corrupt local officials.

“I…uncovered a scam where a systematic diversion of Jersey City’s water had been ongoing,’’ Galdieri later wrote in an email to a popular local blog, Hudson County Facts.

On the eve of the election, in 2005, Galdieri was arrested and charged by Hudson County prosecutors with possessing illegal drugs. He admitted to having ecstasy, methamphetamines and cocaine, and served two years of a five-year prison sentence.

New Jersey state investigators later found widespread financial abuses at the water authority and discovered that some 300 million gallons of water had been illegally diverted during a period when the authority was raising rates for water users.

Galdieri never ran for office again and was murdered in May 2014 by hit men hired by his boss and colleague, Sean Caddle, who admitted paying off Bratsenis and his partner, Bomani Africa, the day after Galdieri was killed.

Caddle’s story is especially riveting stuff for the Democratic bigwigs for whom he consulted in Hudson County and beyond. Former state senator Ray Lesniak, who hired Caddle to run key campaigns, including his 2017 run for governor, says Caddle could be unreliable at times, but never showed signs of being a homicidal monster.

Caddle, Lesniak says, infuriated him by calling him up to chat about politics after news broke of the Galdieri murder plot and his continuing cooperation with the feds. He says he hung up the phone in fury and told Caddle their relationship was over.

“Caddle…was going door-to-door on our campaigns while he was plotting this guy’s murder,’’ Lesniak told New Jersey Monthly in an interview. “How do you do that?”

Caddle’s motive and his ongoing cooperation with federal authorities have riveted political circles as much as any topic since the deaths of Joyce and John Sheridan—just four months after Galdieri was killed.

MISSED OPPORTUNITY

John Sheridan was an elite lawyer who had a storybook family and home life, raising four boys in a large colonial house set amid the pastureland and country clubs outside Princeton. In his final years, he was CEO of Cooper University Health System in Camden and helped engineer a dramatic expansion of the hospital.

Sheridan, like Galdieri, had found himself on the outs with local political forces. In his case, the subject was real estate and lucrative state subsidies that were targeted for the long-suffering city of Camden.

In 2014, a new state tax-break program that would eventually lavish more than $1 billion on the city attracted companies from all over New Jersey to consider new projects in Camden and its run-down waterfront on the Delaware River.

At the head of this wave was Sheridan’s employer, Cooper Medical System, an ever-expanding entity that was a bright spot in a blighted city.

In addition to working as Cooper’s chief, Sheridan volunteered as an unpaid director for Camden’s oldest and most respected community-development group, the Cooper’s Ferry Partnership, a nonprofit that was also looking to use the new tax subsidies to buy property on the waterfront.

Sheridan suddenly found himself caught up in what became a massive tug-of-war between two powerful entities to control a critical—and potentially lucrative—chunk of Camden.

The two sides were tussling over the right to purchase and develop a business park located across from Philadelphia.

Sheridan says the final months of his father’s life were spent entangled in strife between these formidable local competitors. At certain points, he says, his father’s job was at risk as he navigated the treacherous waters. John’s brilliant career was in danger of ending in disappointment and discord.

“This whole conflict very much affected my father near the end of his life. He was under a lot of stress,’’ Sheridan says. “You have to remember that Camden in 2014 was on the brink of a huge building spree that would be financed with those tax breaks. Think of all the money at stake. Millions of dollars were changing hands. My father was in the middle of all that.’’

When investigators arrived at the Sheridan house the morning after the deaths, they found a tumble of documents spread out on the dining room table. Those documents—handwritten notes, memos and copies of emails—were all part of the development saga that had cast anxiety over the final months of John Sheridan.

Sheridan keeps carefully collated copies of the paper trail in a thick file close at hand. Paging through it, he shakes his head.

The documents show a man in distress, a man seeking just solutions to a local land dispute that appeared to have grown personal and vindictive. At points, John appears to be writing memos to himself as he tries to sort out his responsibilities between the competing factions. At best, it is a fragmented paper trail, but it offers a tantalizing glimpse of the thorny issues that dominated the final months of Sheridan’s life.

“The investigators wanted to know what might have been bothering my father at the end; what was going on with him,’’ he says. “This—this was it. But they never cared about looking into it. They never really pursued it.”

Now that the case is reopened, investigators have to decide how far they will go to reconstruct John’s final days. Matt Plakin, New Jersey’s acting attorney general, isn’t giving interviews.

Who will investigators talk to? How far will they delve into the fraught territory of political power struggles and real estate squabbles? Whatever path investigators follow, it’s a good bet they’ll start with the clues John left on his dining room table.

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED?

The four Sheridan brothers have spent eight frustrating years seeking answers to the mysteries that still hang over their parents’ deaths. What really happened in their final, desperate moments? How had the county detectives who investigated the case allegedly botched things so badly, failing to dust for fingerprints, discounting blood spatter in a back hallway, missing a fireplace poker that matched bruises on their father?

There were allegedly so many missteps, so many omissions and missed opportunities by local lawmen and medical examiners that the state was eventually compelled to retract its official finding that John had murdered his wife and then himself, somehow managing to set fire to the bedroom and pull a massive armoire on top of himself at the same time.

“Undetermined” became the official designation for the cause of John’s death, while Joyce’s death remained classified as a homicide.

John and Joyce Sheridan had been married for 47 years when they were found dead in their two-story ’70s-era colonial home in the well-heeled section of Montgomery Township, just north of Princeton.

By all accounts, they had been happily married. Joyce was a public school teacher who took time off to raise their boys. The couple had many friends and spent a lot of their time hunting for antiques.

It was a beautiful, warm and sunny morning on September 28, 2014, when a neighbor called police after spotting smoke coming out of a second-floor front window of the Sheridan house.

When firefighters arrived, they found a horrific scene. The couple’s bodies were sprawled on the floor of the main bedroom. They had both been stabbed to death, and an armoire was lying across John. The room had been set on fire.

Police called all four adult Sheridan sons to come home. When Sheridan, the eldest of the brothers, arrived at the scene, the house was surrounded by emergency responders, and he was not allowed inside.

Investigators outside the apartment of Michael Galdieri, who was found stabbed to death inside his home in May 2014. Photo courtesy of Richard J. McCormack/The Jersey Journal

When Sheridan learned that the Somerset County Prosecutor’s Office was considering calling the case a murder-suicide, he knew right away that they had to be wrong. To his knowledge, there was nothing in his parents’ lives that could have led to a murder-suicide: They were happily married and had no financial problems, no affairs and no issues with addiction.

“I think my parents were murdered; there’s nothing to suggest otherwise,” he says. “I don’t know if there’s a connection with the Galdieri murder, but what struck me was the similarities between the two crimes. In both cases, they were stabbed to death and the rooms were set on fire.”

Joyce had been stabbed 12 times in the head, chest and hands; they were obviously defensive wounds. Sheridan says that not a drop of Joyce’s blood was found on his father, even though blood spatter from his mother was found 6-9 feet away from her body.

“It would seem to be nearly impossible for that to happen if he did it,” he says.

John had five stab wounds, shallow cuts to his neck and torso. County investigators believed that the cuts resembled so-called hesitation wounds similar to those found on people trying to commit suicide, according to the prosecutor. Investigators apparently came to the conclusion within days that John had killed his wife before committing suicide.

When the prosecutor’s office called him and his brothers in for a meeting to explain their belief that the killings were a murder-suicide, the discussion grew heated, Sheridan says. The investigators then demanded DNA samples from all the brothers, even though police had already checked their telephones, E-ZPass, and credit card records and had found nothing to implicate the children in their parents’ deaths.

“The county had their mind made up right away that it was a murder-suicide, so they never collected evidence or pursued leads like they should have,’’ Sheridan says.

A memorial service for Joyce and John Sheridan was held on October 7, 2014, in Trenton, days after they were found dead. Photo courtesy of AP Photo/Mel Evans

Accusations that the county investigation was flawed mounted quickly. There was a bloody fingerprint found outside of the Sheridans’ bedroom that was never explained. Nearly $1,000 in cash and valuables, including expensive jewelry, were left untouched in their room. The house showed no sign of forced entry.

Within days of the deaths, the Sheridan brothers hired forensic pathologist Michael Baden to redo autopsies on their parents. Baden found surprising errors, including a cut on John’s neck that had penetrated his jugular vein and likely killed him.

A weapon that matched the fatal wound, however, was never found. A county investigator who took part in the Sheridan probe later filed a whistleblower lawsuit, claiming the county had made serious errors during the investigation, including improperly collecting, preserving and subsequently destroying evidence in the case.

The Somerset prosecutor’s office declined to be interviewed for this story.

The whistleblower lawsuit was eventually dismissed, and the cause of John’s death was later officially changed from suicide to undetermined. The phrase murder-suicide connected to John still grates on family and friends.

John Farmer Jr., a former attorney general under Govenor Christine Todd Whitman who was a friend to the Sheridan family, says he feels badly that the children have to live with the intimation that their father was a murderer.

“Mark had to explain to his children that his father killed his mother. There’s a lack of empathy there. When I first spoke to him, he was trying to process what they told him,” says Farmer, adding that Mark was understandably outraged about the mistakes in the autopsy.

Farmer said the developments regarding the Sean Caddle case, and news that the Sheridan investigation is being reopened, gives some hope that there may finally be answers for the whole Sheridan family.

“I don’t know if there’s a connection between the two murders, but I do know that the police were very dismissive,’’ Farmer says. “Someone could have staged a murder-suicide like that and covered it up. ”

Many murder investigations, Farmer says, end up hitting brick walls. But, he believes that the state should have a formal process in cases where a murder-suicide is suspected, and the family disputes it.

Sheridan realizes the chances of finding out just why his parents died are slim. Too much evidence is gone or was never collected, he says. Too much time has passed.

But with the state’s new interest in the case, and with the Caddle case percolating, Sheridan has something he has not had for years: hope and a chance for closure.

“Look, I don’t know what happened to my parents, and I am not saying their deaths are definitely linked to” Caddle’s hit man or Camden, Sheridan says. “I’m just saying, let’s finally investigate these issues the way they should have been from the start.’’

If the recent past is any indication, the future courses of both cases are sure to take some intriguing twists. Caddle’s sentencing is scheduled for early December.

Jeff Pillets, an investigative reporter, has won numerous writing awards and was a 2008 Pulitzer Prize finalist.