Illustration: Dan Page

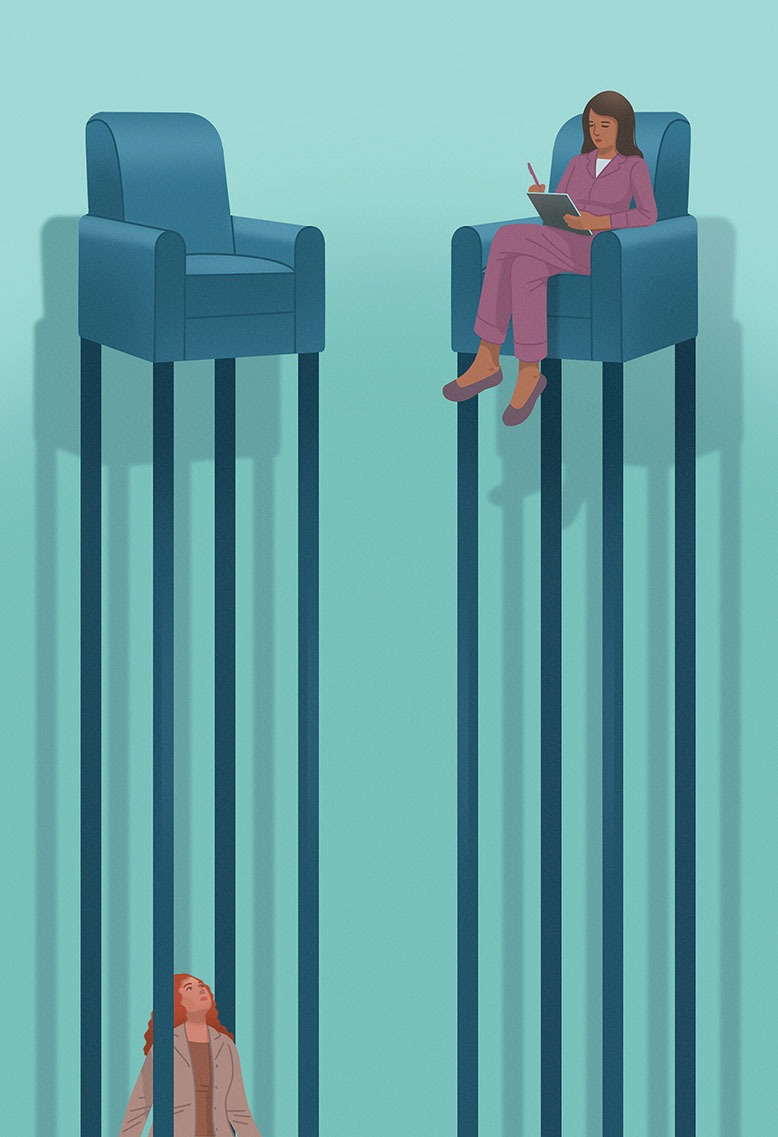

It’s a vicious cycle: At a time when demand for mental health services is rising, there are fewer mental health professionals available to help.

A 2022 survey by the American Psychological Association found that 6 in 10 psychologists aren’t accepting new patients. A study last year by the National Council for Mental Wellbeing found that 9 in 10 behavioral health workers had experienced burnout, and 83 percent were concerned that, without public-policy changes, the critical shortage of mental health workers will continue.

“We’re in the middle of a mental health crisis in this country,” says Kelly Moore, director of the Center for Psychological Services at the Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology at Rutgers. “There’s been a significant increase in the number of people experiencing mental health issues compared to the number of places and people that can help address that.”

Marybeth Munoz (whose name has been changed to protect her privacy) has been trying for months to find a therapist for her 11-year-old daughter. The responses have been discouraging. “It’s, ‘I’m not seeing children; I’m not taking insurance; I don’t have availability,’” she says.

When she has found therapists who fit those criteria, Munoz has encountered another hurdle: The majority offer only virtual sessions.

“That’s not going to work for an 11-year-old who wants to hug her therapist,” she says.

Munoz, who is herself a social worker in a child-abuse program, says that increased demand has made therapists choosier about whom they see and the kinds of sessions they schedule. “I feel like more are saying they’ll just do sessions from home and only work with adults—whatever is easiest for them,” she says.

There has long been a shortage of mental health workers in the United States, something Dr. Gary Small, chair of psychiatry at Hackensack University Medical Center, attributes to the fact that mental health workers are not adequately compensated for their schooling, training and time spent with patients, and are also under-reimbursed by insurance.

But the Covid-19 pandemic, he says, pushed that shortage into overdrive. “There was a pandemic within the pandemic,” says Small. “There was more social isolation, fear, anxiety, loss, financial challenges—all kinds of problems that were affecting people.”

The result: more demand for social workers, marriage and family therapists, substance-abuse counselors, psychologists and psychiatrists.

[RELATED: The Mental-Health Aftershocks of Covid-19]

At the same time, in the Garden State, personnel problems at the New Jersey Board of Social Work Examiners, the licensing board for social workers, caused long delays in granting licenses, and fewer social workers entered the system at a crucial time.

Teletherapy, or sessions conducted over video, has helped get more people access to services. The downside is that the personal touch can be lost. “You can’t see body language the same way,” says Moore.

There are also practical disadvantages, she says. Clients don’t have as much privacy and can be more distracted when they’re on the computer at home.

Still, teletherapy can remove barriers to those who need mental health services by reducing the costs of transportation and childcare and opening up more potential appointment times, she says. For those in less densely populated parts of the state, where therapists are scarcer, it can provide valuable options and access.

Digital therapy can be a natural for young people, who are accustomed to doing everything online, Moore says. And therapists for teens and GenZers are in especially high demand. Depression among young people had been rising steadily even before the pandemic, which amplified the trend as it caused isolation, uncertainty, loneliness and loss. According to the National Institutes of Mental Health, an estimated 20 percent of 12- to 17-year-olds had a major depressive episode in 2021.

One potential barrier to teletherapy is the fact that the licensing boards require therapists to be licensed in the state where the client is receiving therapy. That can be a problem for college students and others who move out of state and must leave their New Jersey therapists’ practices.

A bill before the state legislature would make New Jersey part of an interstate agreement known as the Counseling Compact, allowing counselors who are licensed and living in a member state to practice in other member states even if they’re not licensed there. New Jersey psychologists already benefit from a similar program called Psypact, which requires member states to honor the licenses of psychologists from other states in the group. For example, a New Jersey student at college in Connecticut can continue online therapy with a New Jersey psychologist, since Connecticut is a member. So far, 32 states have joined; check psypact.com for members.

Choosing a therapist can also be daunting because of the range and types of services that are available. The majority of therapists use cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which helps clients become aware of inaccurate or negative thoughts so they can respond to challenging situations more effectively. Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) can be effective for conditions such as substance abuse, borderline personality disorder and eating disorders, by introducing healthier ways to control intense, negative emotions. Somatic therapy, eye-movement desensitization reprocessing (EMDR) and other treatments that emphasize both body and mind are often used to help survivors of trauma, but can also be useful for an array of mental health diagnoses.

A helpful tool in finding a therapist is the Psychology Today website. In addition to searching for practitioners in your geographic area, you can filter for the issues you need help with, type of therapy, insurance, gender, price and many other criteria. Websites for professional organizations related to a condition or therapy, such as Somatic Experiencing, are another potential resource.

You can also check with your insurance carrier, who can provide a list of in-network therapists.

For many people, simply paying for therapy is a big hurdle. Because insurance companies typically offer low reimbursement rates to therapists, many don’t accept insurance, leaving clients to submit claims privately.

That can mean paying out of pocket for months until deductibles are met. With rates typically in the range of $150 an hour, clients can be looking at monthly bills of upwards of $600.

Students enrolled in college can generally get free counseling and psychological services on campus. Due to the therapist shortage, they may not be able to get counseling as frequently as they’d like, but they may be able to supplement with other services, such as group therapy and substance-abuse counseling, Moore says.

Another avenue is clinics affiliated with psychology graduate programs at medical schools or universities like Rutgers and Rowan.

At Rutgers Graduate School of Applied and Professional Psychology, doctoral students treat community members under the supervision of a licensed psychologist at a much lower cost. “They do a really great job,” Moore says. “They’re eager, and they’re following treatment protocols to a T, so you can really get good services.”

Once you connect to a therapist, it’s crucial to find a good personality fit. “It’s a bit like dating, where you get a sense of, ‘I feel comfortable with this person,’” says Small.

Finding a therapist requires patience and determination. “A lot of people are afraid of their own mental struggles; there can be discomfort around sharing your vulnerabilities,” says Small. “So people don’t get help when they need it, and it gets worse.”

Deep down, there can be the feeling that therapy won’t help. “There’s a misperception that there’s nothing really that can be done, that there are ineffective treatments,” Small says. But that’s not true. “In recent years systematic studies demonstrate that talking therapies make a real difference in many different conditions,” he says.

Small sees an upside to the difficulties of finding a therapist. “One of the silver linings to the pandemic is that it brought mental health problems to the forefront, and people are seeking out help,” says Small. “The stigma is diminishing, and that’s a positive thing.”

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.