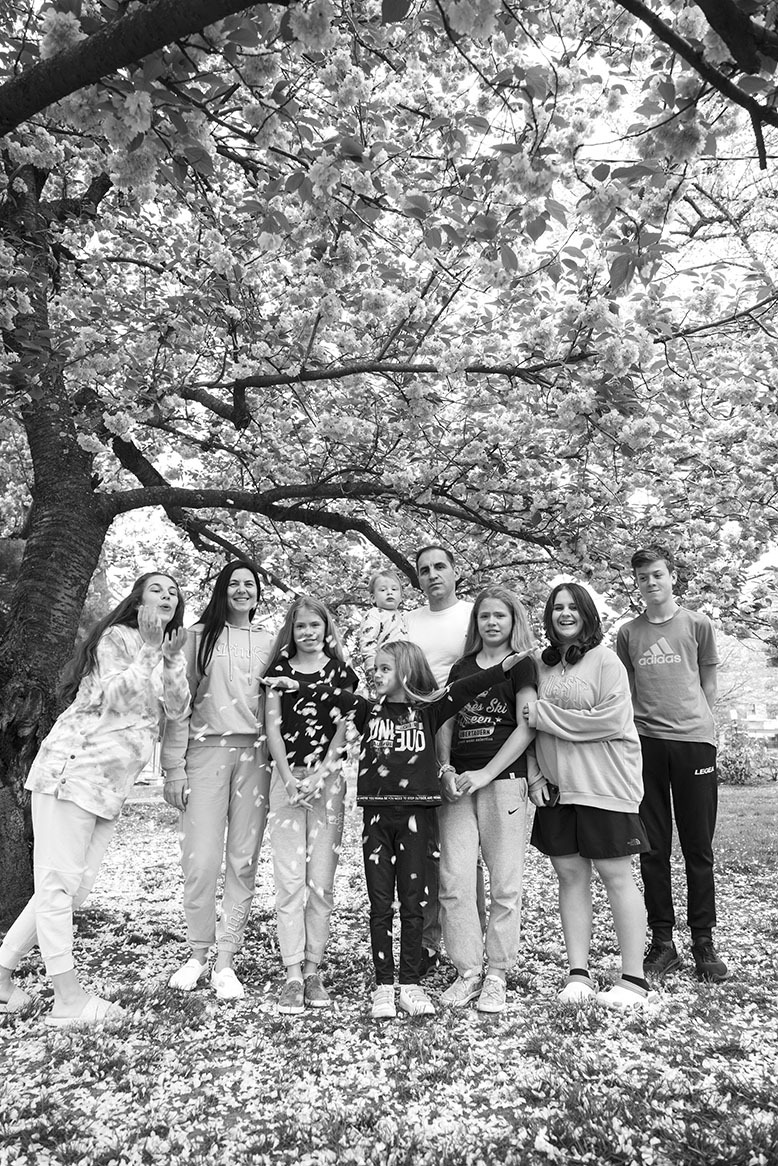

The Chernets family (L-R): Anya, matriarch Alyona, Kristina, patriarch Vadym with Anya’s son, Jessika, Izabella, Diana and Ruslan at their New Jersey home. Photo by John Emerson

On February 24, 2022, the day bombs and missiles began falling on the city of Kyiv, one Ukrainian family began a journey that would carry them halfway around the world to the United States—specifically, to a leafy suburb in northern New Jersey.

The Chernets family’s ordeal began with the horrific realization that the Russian military presence in their home country was not simply a menacing threat from President Vladimir Putin. It was a true invasion.

“We didn’t think it could happen,” Vadym Chernets, a father of seven, recalls months later. “We thought it was a provocation, political theater. Then, at 6 am, our walls and windows started to shake from the explosions. My wife, Alyona, said to me, ‘This is war.’”

On that chilling day in February, the Chernetses could not have guessed that, by springtime, they would be living in Ridgewood, New Jersey. Sitting around a conference table in April at Temple Emanu-El in nearby Closter, they relayed their story to New Jersey Monthly with the help of translator Arnold Rozenblum.

“The only thought we had was to stay alive, to get out of Kyiv and save our children’s lives,” Vadym told us from his adopted home 4,600 miles away from Ukraine.

Alyona and Vadym Chernets at their family’s Ridgewood house. Photo by John Emerson

The family traveled through many places, including Moldova, Poland, Romania, Germany, France, Mexico and New York, before settling in New Jersey, where Rabbi David-Seth Kirshner and his congregation at Temple Emanu-El provided them with shelter, supplies, donations from the community, and a warm welcome.

The Chernetses are not Jewish, but helping them was rooted in Jewish tradition, says Kirshner. “There were people in history who saved Jewish people and who went through much more peril to do so. Generations are alive today because of it,” he says. “We can proclaim as much as we want, never again, never again, but when people need a place to land, or people need food or people need support—you see what I’m saying? If never again means never again, then you’ve got to act on it. It can’t just be words.”

***

In the suburbs of Kyiv, Vadym, Alyona and their seven children had lived in safety and comfort. Their household was a large and busy one, filled with active schoolchildren and professional adults. Vadym, who holds a PhD in economics, worked as a developer for a project-management team, and Alyona was employed as a family-planning and fertility consultant.

But on that terrible February morning earlier this year, the life they had known vanished. Suddenly, there was no school, no work, no plan. Artillery was screaming through the sky, and the family was huddled together on a row of mattresses in their cold, dark basement. The explosions sounded terrifyingly close, outside their windows. “We were at the front lines,” Vadym says.

For several days, the family lived in the basement, listening to news reports and praying the conflict would be resolved quickly. That didn’t happen. Finally, Vadym told Alyona, “You and the children should leave Ukraine. I will stay and fight.” But Alyona refused to go. “We have too many children to look after by myself,” she told him. “Either we go together, or we don’t go at all.”

Vadym and Alyona are the parents of two grown children—Dmitro, 25, a graphic designer and food technologist, and Anya, 23, a philologist—as well as school-age kids Diana and Ruslan, both 14; Kristina and Izabella, both 10; and Jessika, 7. They had all resided in the family’s Kyiv home, along with Anya’s husband, Michael, and their 1-year-old son, David.

The Chernets family’s oldest child Anya, 23, with her son David. Photo by John Emerson

A decision had to be made: leave Kyiv or stay? The moment came when their friend, a former school bus driver who had been drafted into the Ukrainian army, called to check on them. “He said, ‘I’m in occupied territory. I see how dangerous they are. I see what they’re doing to civilians,’” Alyona remembers.

“They” were the Russian army, known locally as the Kadyrovtsy. The friend told them he had seen soldiers breaking into homes and abusing civilians. The family knew things could get worse fast. They feared the Russian forces would begin committing wartime atrocities—rape, mass shootings, torture. That is allegedly what happened soon afterward, in cities like Bucha and Mariupol.

Alyona was haunted by the thought of what might happen to her family if they stayed. “I was afraid Kadyrov soldiers would come and rape my children,” she says quietly. “We have five girls.”

In their rush to leave, Vadym forgot his socks and Anya forgot her son’s birth certificate. They piled into the family car, all 11 of them, not knowing where to go, how long they would be gone, or what they would come back to.

In February, Vadym says, the family simply planned to drive around for a few days, hoping the conflict would be over soon. The long hours in the car were hard on the children, who were restless and bored, and especially difficult for oldest daughter Anya, who was seven months pregnant at the time. The adults tried to keep the kids’ spirits up and tried not to panic. They searched for reliable news about the war. Social media offered some, but they couldn’t tell how much of it was rumor. They heard their country was fighting back furiously, staving off the quick Russian victory many people had expected. Could that be true? Did Ukraine actually have a chance of winning?

Alyona and Vadym’s daughter Jessika, 7. Photo by John Emerson

At night, the family slept in their car. Cities all over Ukraine were being bombed by then. No place felt safe anymore. On the third night, they made the decision to leave Ukraine. The Moldovan border was closer than Poland, so that’s where they headed.

However, the family was unprepared for the chaotic scene that awaited them. They said afterward it was like a nightmare. Air raid sirens were sounding constantly. Everyone was tense with fear, knowing an air strike could happen at any moment. Heavily armed Ukrainian border guards were stopping every car, pulling out men of fighting age (18-60) and ordering them to stay and defend their country, the Chernetses recall. Women and children were allowed to continue to the border, but because some Ukrainian women didn’t know how to drive (“They rely on their husbands,” Alyona says), many lost control of their cars. According to Vadym, there were multiple car crashes from the checkpoint to the border, and disabled vehicles were everywhere. The cold night air was filled with cries and screams. The family felt sick and terrified, listening to the sounds of war around them. In the darkness, they heard cars colliding, the rushed goodbyes of families being torn apart, the ominous moan of air raid sirens.

The Chernetses’ car was hit by another car at the border, Vadym says. “When I looked into the driver’s eyes, they were blurry. He said, ‘I’ve been driving for 14 hours to get my family out.’ He tried to bribe the border patrol with his car so he could stay with his family. But they would not let him leave.”

Vadym braced himself to be separated from his family. But the border patrol told him that, as a father of more than three children, he was exempted from military service. Dmitro and Michael, however, were pulled out of the car at gunpoint.

“We didn’t even have a chance to say goodbye,” says Vadym, becoming emotional. “It was cold. They were not ready. It was dark. 2 am. We were parting. We didn’t know what to do. When we crossed the border, Anya got out of the car and vomited.” Alyona says, “She was in shock. There are a lot of details from that night that Anya doesn’t want to talk about.”

Dmitro and Michael expected to be drafted on the spot, but in later communications with their family, they said they had been assigned to work with a team of volunteers at a church in Moldova. Vadym’s face showed the pain of his ordeal when he told us, “I’m ashamed that I was not able to fight for my country. I have a wife and seven children. I have to take care of them. But if Dmitro and Michael are asked to fight, they will.”

***

After being separated from Dmitro and Michael, the family left Moldova and moved on to Poland, Romania, Hungary, Germany and France. They hoped to get into England, but were turned away. Then, on March 24, President Joe Biden announced that the United States would accept 100,000 Ukrainian refugees.

The Chernetses applied immediately for travel visas at the American embassy in Brussels. There, something remarkable happened.

“We were applying in the American Embassy when we met a colonel of the U.S. Army,” Vadym says. “This gentleman, George, said, ‘As a military man, I would like to help Ukraine. I would like to be there myself, but my country won’t allow me.’ He and a friend, Jesse, invited us to stay at their homes.”

“We trusted them,” Alyona says. “Kindness was written on their faces.” That week, Jesse and his wife, Randi, created a fundraising page on Facebook for the family.

“The money she collected was enough to get all of us to Cancun, Tijuana, San Diego and then New York,” Vadym says, still incredulous at their good fortune. “For nine people, that’s more than $10,000. Randi said she was doing us a mitzvah.”

That mitzvah, or good deed, was what ultimately led them to Rabbi Kirshner in Bergen County, New Jersey.

The Chernetses moved into their four-bedroom bungalow after members of Closter’s Temple Emanu-El congregation fixed it up for them. Photo by John Emerson

Before he ever met the Chernets family, Kirshner and his 800-member congregation at Temple Emanu-El were already helping Ukrainian refugees overseas. On March 20, less than a month after the war started, Kirshner led a delegation of religious leaders from northern New Jersey to Ukraine and Poland to deliver tens of thousands of pounds of humanitarian supplies that had been collected by the people of New Jersey.

“As much as photos and TV bring the war into your living room, when you see the face of a young mother with her young family not knowing where they’re going to go, what they’re going to do, there’s no picture in the world that adequately expresses the pain of that,” recalls Steve Rogers, a member of Kirshner’s delegation and the CEO of the Kaplen JCC on the Palisades. “These are people who look no different from you and me, who could be from any town in New Jersey, whose lives have been reduced to one bag. Their husband or father or son has been left behind to fight. It was terribly, terribly heartbreaking.”

Returning home to New Jersey, both Kirshner and Rogers were struck by the global consequences of the Ukraine-Russia conflict. “Close to 14 million people displaced,” Rogers says. “How do you handle that? Basically, the entire free world has to work together to solve this.”

Rabbi David-Seth Kirshner and his congregation at Temple Emanu-El in Closter helped the Chernets family plant roots in nearby Ridgewood. Photo by John Emerson

Kirshner says that once he connected with the Chernets family, members of his congregation stepped up: “We realized that we spoke a lot of common languages. And I’m not talking about literal languages. We created a bond and a friendship, and we still consider them a part of our extended family.”

After traveling so far, the Chernets family wound up in New York’s Chinatown neighborhood. They stayed there for a few days “because it was cheap,” says Vadym.

Unlike some places in Europe, where refugees were offered lodging, food and supplies, in New York, they felt like they were on their own. President Biden’s offer to welcome 100,000 Ukrainian refugees did not seem to have any practical effect on their day-to-day lives, the Chernetses say.

It would be another month before Biden announced an immigration initiative called Uniting for Ukraine, designed to offer safe haven to Ukrainian refugees fleeing the war. The program offers recipients (who are vaccinated and vetted) legal status for two years. To qualify, they need an American sponsor.

But in late March, when the Chernets family crossed the border from Mexico into the United States, they could only apply for Temporary Protected Status, a designation offered to people fleeing a conflict zone. TPS permits them to stay in the United States legally for 18 months.

When the family arrived in New York, they did not know where to go or what to do. Vadym reached out to their friends Randi and Jesse from Belgium. Randi told him she had a friend, Rabbi Kirshner in Closter, who could possibly help them. Soon after, Vadym recalls, “we were picked up by a minibus in Chinatown. A driver loaded all of our stuff into the car and brought us to New Jersey.”

For three weeks, the family lived in a private home in Closter arranged by the temple. The congregation and the rabbi’s wife cooked them nutritious meals and gave them everything they needed: comfortable beds, clothing, toys, even a computer for every member of the family. They brought them to doctor’s appointments, baseball games and the hairdresser. The children met superhero characters in Times Square, and were delighted with trips to the Staten Island Ferry and the Statue of Liberty.

“We are so grateful to the kind rabbi and his congregation,” Vadym says, his eyes filling with tears. “Without them, what would we have done? We would have been on the street.”

On April 25, nearly two months after leaving their homeland, the family moved into a house of their own. Through Valley Hospital in the town of Ridgewood, the synagogue—which has been helping the family out of kindness and is not their official sponsor—was able to rent for them an old but charming four-bedroom bungalow.

According to the Chernetses, members of the congregation had spent weeks painting and repairing the interior of the house, installing sturdy used appliances, and donating furnishings. There is a big backyard for the children. From a glass-enclosed side porch, they can see, in the front yard, a beautiful, pink-blossomed tree. It was in full bloom the week they moved in.

New life also joined the family on May 21, when Anya and Michael welcomed their second child, a daughter named Elizabeth Grace.

Vadym, who does not know when he will get a work permit in the United States, says that any Ukrainians who find their way to New Jersey are welcome to visit their new home any time. “As soon as I saw this house, I thought: I’ve come home again.”

HOW TO HELP

A number of New Jersey groups are helping Ukrainian refugees living here and overseas.

- The Ukrainian American Cultural Center of New Jersey in Whippany is accepting donations of medical and military supplies. Urgently needed items can be found on the group’s Amazon wish list.

- Meest-America in Port Reading is collecting millions of pounds of medical and tactical supplies, vests, helmets, food and sleeping bags. Monetary donations cover shipping costs.

- The New Jersey Hospital Association and the Ukrainian National Women’s League of America send medical supplies to Ukraine. Monetary donations to purchase and ship supplies, as well as donations of medical supplies, medications and equipment from health care providers, are being accepted.

- Quest Diagnostics Foundation, based in Secaucus, has partnered with Project HOPE to deliver medical supplies and assistance to Ukraine. Monetary donations are being accepted.

- Ukrainian National Home Community Center in Jersey City is collecting medical supplies, blankets and tactical equipment for Ukrainian military and civilians.

- The state of New Jersey website lists ways residents can help by donating supplies and more. Contact your local church, synagogue or civic center. Many have been holding fundraisers and collecting supplies.

INTERESTED IN SPONSORING A UKRAINIAN REFUGEE?

Sponsors must be legal U.S. residents and be able to prove they can provide reasonable accommodations and living expenses.

- Welcome.US is a humanitarian group focused on refugee resettlement that can help connect refugees with American sponsors.

- Razom for Ukraine helps connect refugees with American sponsors and pro bono legal counsel.

- Ukraine Take Shelter was launched by two Harvard freshmen to connect people fleeing Ukraine with sponsors in safer countries.

Linda Federico-ÓMurchú is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in NBC News, Today, CNBC, MSN, TheStreet.com, NJ Spotlight, and many other publications. She is the author of two books in progress.

Special thanks to translators Yulia O’Connell, a volunteer at razomforukraine.org, and Arnold Rozenblum, a member of the Temple Emanu-El congregation.