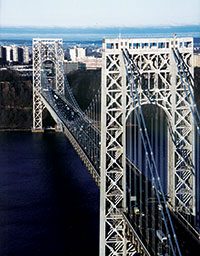

On April 11, 2006, Robert Durando, general manager of the George Washington Bridge, and Robert McKee, physical plant manager, took me on a tour of bridge facilities the public never sees, some of which I didn’t know existed. As general manager, Durando supervises some 220 full-time staff members while McKee manages regular and long-range maintenance.

Durando, McKee, and I began our tour of the bridge on the south walkway heading east toward the New Jersey tower. We passed the monument to Bruce Reynolds, one of the thirty-seven Port Authority police officers who died on 9/11 at the World Trade Center and the only one whose regular assignment was the G.W.B.

At the New Jersey tower, a security guard unlocked the high cage topped with barbed wire that surrounds the south side of the tower where it passes through the bridge roadway. Despite their positions, Durando’s and McKee’s credentials were checked as carefully as was the pass they had secured for me. Inside, we stepped into a small rack-and-pinion service elevator.

First we descended the tower to the south concrete platform at its base, which at this time was some fifteen feet above the river; at high tide more of the platform is covered. The base goes down about 100 feet to bedrock. Half of the New Jersey tower rests on this platform, eight giant steel feet bolted to its surface, the other eight bolted to the north platform. While the New York tower stands on rock jutting out from Manhattan, the center of the New Jersey tower is seventy-six feet out into the Hudson.

The tide was running out at that hour. We were under fourteen lanes of rushing traffic—currently 300,000 vehicles per day, 2.1 million per week—yet down below it was tranquil and quiet, the water lapping about the giant platform, and I kept thinking what a splendid place this would be to go fishing.

My fishing fantasy was set aside when we reentered the elevator and slowly rose through the roadside level and up, up above the tower’s great arch, where there is a kind of mezzanine. Dismounting and moving left,

we entered another tiny elevator that rises just short of the level on which the saddle rooms are found. Climbing additional levels of steel stairs, we entered the north saddle room.

In each of the saddle rooms in both towers, two of the huge barrel cables pass over heavy steel structures known as “saddles,” which support the barrel cables atop the towers. Created on-site, the barrel cables are three feet in diameter, each containing 26,474 galvanized steel wires, spun one at a time across the river. The barrel cables are instrumental to the functioning of the bridge. Attached to them are the much thinner suspender cables, or “stringers,” that descend to support the roadway.

I had thought the barrel cables must be greased so they could slide back and forth over their saddles, responding to the weather and the number of heavy vehicles traveling over the bridge, but, as Durando pointed out, if they did that they would quickly wear out. The cables are actually bolted to the saddles. It isn’t the barrel cables but the towers themselves that flex ever so slightly. Bridge engineers talk about “dead weight” and “live weight.” Dead weight is the bridge itself; live weight, the traffic passing over it. The George Washington is built so solidly that its live weight, as bridge staffers are fond of saying, is “like an ant on an elephant’s back.”

Nevertheless, in one way or another, all of the bridge moves. In hot weather the barrel cables and suspender cables expand; in cold they contract. Thus the roadways may be lower in summer, higher in winter. There are also steel finger joints in the bridge road surfaces that expand and contract horizontally in response to the weather. McKee said, “A suspension bridge like the George either moves or it cracks and falls into the river. A bridge like this doesn’t just stand there; it’s a machine. It’s almost alive.”

From the saddle room we ascended one more level to reach the open-air space atop the tower, accessible via a hatch in the ceiling. To get up there we climbed a ladder—not a leaning ladder you’d climb to clean out the gutters on your house, but a straight-up-and-down ladder with thin steel rungs set so close to the bulkhead there was only room for my toes.

At the bridge summit I found myself on something much larger than I expected, because I hadn’t anticipated that here both sides of the tower come together. In form and size the area resembled a tennis court with a parapet around it. Indeed, when the bridge was under construction there were plans to put restaurants or observation decks atop one or both towers.

Atop the bridge tower I felt privileged to be in a place few others will ever see. I felt incredibly free up there. I felt, well, high. At 604 feet up in the sky, you’re removed from everyday cares. Durando and I hung over the parapet drinking in the scene—the barrel cables descending at steep angles on both sides, the suspender cables dropping vertically from the barrels to hold up the bridge deck, the unending stream of trucks, buses, and automobiles, from that height resembling miniature toys.

I had the sense McKee didn’t exactly share this feeling. He was staying well back of the parapet and looked a little green. “You okay, Bob?” I asked.

“Yeah, fine,” he said. “I’ve just got a fear of heights.” This struck me as singular. The man in charge of bridge maintenance, of these very towers, has a fear of heights.

Luckily, I have no particular fear of heights. Just then, I was afraid of something entirely different. There were several huge peregrine falcons in nests not twenty feet away. The last thing I had expected to find atop the towers of the George Washington Bridge was wildlife. These raptors make their homes there. The birds glowered at me, and I decided it would be better to give them a wide berth. I didn’t want one of these things suddenly coming at me, certainly not up here on top of the world. The pigeon feathers and bones surrounding the falcon’s nests testified to their hunting prowess. Bob McKee said, “There’s nothing quite

like a peregrine going for a pigeon. It’s like a shotgun blast.”

There was another item of interest atop the New Jersey tower: the huge cylinder that, passing through the upper part of the bridge, emerges at the bottom of the arch. It houses the largest free-flying flag in the world. This sixty-by-ninety-foot American flag, ever since 1948, has been deployed beneath the arch on national holidays. The current flag, made of nylon and wool, weighs 450 pounds and can be flown only on days when the wind doesn’t exceed fifteen miles an hour—anything stronger would tear it to shreds.

We went down the vertical ladder—even more difficult than going up—and the flights of steel steps, and then we took the two elevators down to bridge level. Durando led the way on the south walkway as we headed west and approached another caged doorway, with accompanying security guard and security system, close to where the south barrel cables pass through the bridge deck into the New Jersey anchorage.

We descended into a world quite as unique as the one atop the tower, a vast room hollowed out of Palisades rock. Here, two giant barrel cables enter, and each splits into sixty-one strands three inches in diameter that are tied to the rock. Workmen were down in the anchorage that day installing a dehumidification system to deter cable rust.

I asked Bob McKee how long he thought the George Washington Bridge would last if properly maintained. “Probably another 125 years,” he said. “At that point keeping things up might be so demanding and expensive it wouldn’t be cost effective.” That means that the bridge is projected to last 200, because this was 2006 and we were six months away from its 75th anniversary.

Great skill and wisdom obviously went into building the George Washington. The Pulaski Skyway, the series of cantilever truss bridges connecting Newark and Jersey City over the Meadowlands, was completed a year after the George. It has now been declared obsolete, with plans afoot to replace it. The Tappan Zee Bridge, the most important bridge over the Hudson north of the George Washington, is also considered obsolete, if not dangerous, in need of replacement after only a half century of use. On August 1, 2007, the I-35W bridge over the Mississippi in Minneapolis, only 40 years old, collapsed during the evening rush hour with numerous deaths and injuries. It was the seventh American bridge in the past decade and a half to collapse.

It is not comforting to know that one out of five extant American bridges is structurally deficient and many others are in serious need of remediation or replacement. The venerable George is not one of them.

Copyright © 2008 by Michael Aaron Rockland. Reprinted by permission of Rutgers University Press.

If you missed the first installment: Knocking on Heaven’s Door, please click here.

Click here to read the third installment: Building the Bridge.

Click here to read the fourth installment: The Martha.

Click here to read the fifth installment: Drams, Dangers and Disasters.