With the arrival of Black History Month, I’ve been pondering the important contributions of some of New Jersey’s most illustrious African-Americans. Some are more famous than others; several influenced me personally.

Let’s begin with Gus Heningburg, a highly respected Newark-based activist and negotiator who died in October. Starting in the 1970s, Heningburg was the host of and driving force behind the long-running NBC public affairs series Positively Black. But more than that, he was a giant, widely credited with helping integrate the state’s construction trade and breaking down other racial barriers.

“Gus’s contribution was multilayered,” says historian and Rutgers University professor Clem Price. “He was involved in housing reform, the desegregation of high school referees in New Jersey sports, and it is fair to say, Gus was among a cadre of white and black leaders who helped put Newark back together after the ’67 riots.”

Heningburg often met with my father, Steve Adubato Sr.—a community leader in Newark’s North Ward—to discuss complex and sensitive racial issues. But it was Heningburg’s work as a broadcaster that greatly influenced me to go into television.

Donald Payne is another giant African-American figure who died last year. In 1989, Payne became the first African-American from our state in the U.S. Congress, succeeding Peter Rodino, who served for more than 40 years in the House. Payne grew up in Newark’s North Ward among mostly Italians and other ethnic groups. That helped him in later years deal with people from all walks of life.

Replacing Rodino was no easy task. “Payne represented Newark extremely well,” says Price. “He succeeded an enormously popular and longstanding Italian-American Congressman, Peter Rodino. Ethnic succession in American politics is a difficult transition. But in this case, a black Congressman coming in, just how does he stand on the shoulders of someone like Rodino, who was iconic? As it turns out, he stood on Rodino’s shoulders well.”

Payne’s contributions include his advocacy for the people of Central Africa and the issues they faced. His voice was critical in focusing attention on this often-ignored part of the world.

Wynona Lipman was another political pioneer. In 1971, she became the first African-American female in New Jersey to serve in the state Senate. Lipman represented her Newark constituents for 27 years in an environment that was decidedly old school New Jersey. It was extremely difficult for a black female to work with Trenton’s white, male establishment on issues such as urban poverty, nutrition and health. But Lipman did it—and did it with class.

Among the many legendary black athletes from New Jersey, the one that stands out for me is Larry Doby. Most know that Jackie Robinson broke the color line in baseball in the National League in 1947. But it was only 11 weeks later that Doby—who was born in Camden, grew up in Paterson and later settled in Montclair—broke the color line in the American League.

Doby was a class act. In 1988 I interviewed him about his experiences as a baseball pioneer. What struck me was that he never seemed angry or resentful about the insults and indignities he endured on and off the field. Robinson deserves tremendous credit for his contributions to baseball and our country, but Doby’s role was no less important.

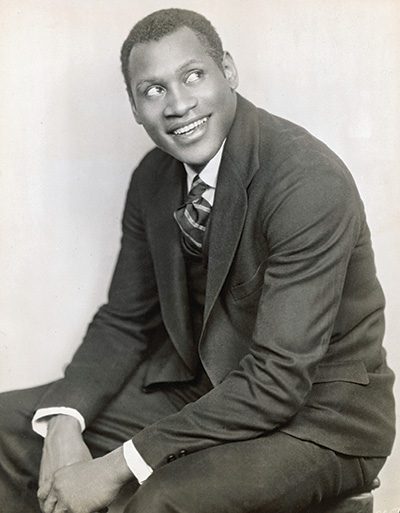

Another ground-breaker was Princeton-born Paul Robeson, who in 1915 became the third African-American to attend Rutgers University. “He was an enormously popular scholar and athlete, giving the valedictory address to the class of 1919,” says Price. “What he had to say as a black man to a sea of white faces was extraordinary.” Robeson accomplished much in his life as a performer and social activist, but his connection to Rutgers is especially significant for New Jersey.

Which other African-American figures from New Jersey do you think should be recognized during Black History Month? Write to me at [email protected]