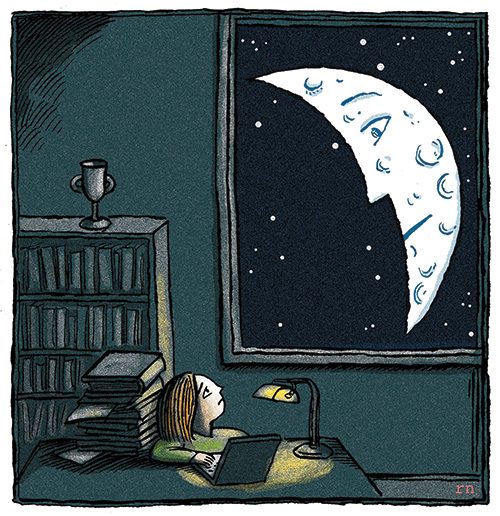

Maggie Spector-Williams, a pretty 13-year-old with dark hair and strikingly fair skin, sits in a rocking chair in the living room of her family’s early-19th-century house in Nutley, looking anything but comfortable. She’s here to talk about homework, but you get the sense from the way she’s white-knuckling the arms of the chair that she’d rather be in her bedroom upstairs, actually doing the work. It’s 6 pm, after all, and she’s

still got hours of toil ahead of her. Homework is okay, she says, glancing at her mom as if she wants to make sure she’s saying the right thing.

“It was a lot worse last year in sixth grade,” Maggie adds, still sounding tentative. Then, as her mother gives her dispensation to leave, Maggie lets loose a sigh. “It takes so much time it literally consumes my life,” she says as she makes her way upstairs. “It’s awful.”

In living rooms, bedrooms and at kitchen tables across the state, homework is apparently consuming the lives of lots of kids, many of them, like Maggie, bright, hardworking and self-motivated. “Sometimes I go up there and it’s 10:30, and I have to tell her to stop so she can take a shower and get to bed,” says Carol Williams, Maggie’s mother. “Sometimes, she gets up early just to finish work from the night before.”

Williams worries that her daughter isn’t getting enough sleep—“let alone,” she adds, “the physical activity and fresh air kids are all supposed to be having. Where do they fit that in?”

Questions about the pros and, increasingly, the cons of homework are being asked more and more often, and not just in private. In a number of school districts across the state, beleaguered parents are raising their concerns about the burden of homework—piled on nightly, on weekends and even over holiday and summer breaks—and administrators are responding by revamping homework policies. In 2000, in a move that some credit for igniting a national movement to reexamine and, in many cases, restrict homework, the Piscataway school board voted to limit teachers’ discretion to give after-school assignments. Under the new policy, homework for students in grades one to three can no longer exceed 30 minutes per night; the limit for fourth- to sixth-graders is 60 minutes; for middle and high school students, 90 minutes and two hours, respectively.

That’s considerably less than the norm. A University of Michigan study found that the average amount of time spent on homework among kids ages 6 to 17 increased from roughly two and a half hours in 1981 to just under four hours in 2004. As it happens, a good portion of that increase was borne by the youngest kids: According to research published in the Journal of Marriage and Family in 2002, 64 percent of 6- to 8-year-olds were likely to be assigned homework on any given school night, up from 34 percent in 1997.

The increases can be traced, at least in part, to A Nation at Risk, the 1983 report issued by the Reagan administration’s National Commission on Excellence in Education, which sounded an alarm about the American educational system’s flagging ability to turn out a competitive workforce in an increasingly technology-based, global economy. Across the country, schools struggled with ways to make their curricula more relevant and rigorous, and homework burdens escalated in response. The 2001 No Child Left Behind Act, with its emphasis on standardized testing, did nothing to ease those burdens. But as the new century dawned, international learning assessments indicated that American students were continuing to trail their peers in countries such as Japan, the Netherlands and Australia.

Enter Race to Nowhere, the 2009 documentary that painted a picture of students bowed under a load of homework for homework’s sake, and an educational system whose focus appeared to be less on education than on getting increasingly stressed-out kids into prestigious universities. If you haven’t seen the film, that’s probably because it was never in traditional theatrical release; instead, it was, and continues to be, available for screenings by concerned individuals and organizations like parent-teacher associations. It seems to have struck a particular chord in New Jersey, where the producer says it has been screened 200 times to date out of a total of roughly 1,000 viewings worldwide.

Valerie Goger, who recently stepped down as superintendent of schools in Bernards Township, spearheaded a district initiative in the 2011-2012 school year to study the issue of student stressors; the initiative began with viewings of Race to Nowhere by faculty and parents. The film, which calls on educators to eliminate homework on weekends and during school breaks, clearly had an effect. “An overwhelming sentiment expressed by parents about homework and projects assigned over school recess breaks caused us to institute homework-free recess periods,” says Goger. “We believe this should allow students to manage their time and balance long-term assignments in consideration of family activities.”

Race to Nowhere was also a motivating factor in the 2010 decision by administrators at Ridgewood’s Benjamin Franklin Middle School to bar homework for elective classes such as creative writing and environmental science. “We wanted to make sure that we weren’t punishing our students with undue stress, and that we were respectful of all of the other things in their life,” says principal Anthony Orsini.

In fact, the so-called homework wars, at least as waged in the Garden State, don’t amount to an all-out attack on homework, but are more an effort to restore balance in the lives of students and their families. In 2012, for example, the Galloway Township school district banned written assignments on weekends for students in kindergarten through sixth grade, a move that was partly motivated by socioeconomic considerations. “We’re 15 minutes outside Atlantic City, and many of our parents work in the casinos,” explains superintendent of schools Annette C. Giaquinto. “If you’re a casino employee, you want weekend hours—you’re making more money. But that means you don’t have a lot of time to check your kids’ homework over the weekend.”

For many parents involved in the movement to limit homework, sleep is as important as family time in the balance they are struggling to achieve. It certainly was for Dr. Anne Robinson, a pediatrician and mother of three in Ridgewood, who had been talking with the principal of Ridgewood High School about ways to ease the stress on students for about a year before Race to Nowhere was released. In 2010, she sponsored three screenings of the film to packed crowds.

“The reason we keep going back to homework,” Robinson says, “is that when you look at the student day, the reality is that they’re spending seven and a half hours in school—a full shift by any definition—and then they’re sent home with a second shift of homework. They have a nine-hour sleep requirement, and they have an early start time.”

Students, with little power to change the homework load or the starting bell, often find that sleep is the one thing they can sacrifice. In December 2011, with that in mind, Ridgewood High introduced its first-ever homework-free holiday break, and last spring it instituted Sleep-In Wednesdays—classes start at 8:45 am, one hour later than usual—allowing students at least one extra day a week to more effectively restore mind and body.

For some of the parents looking to achieve that elusive balance, these and other small changes instituted over the past several years have not done much to alter the day-to-day angst engendered by homework. One Bernards Township parent with two children at Ridge High School says that, while she is grateful for the district’s recently instituted homework-free breaks, her daughter, a sophomore, is still spending four to six hours every weeknight on homework and seven to eight hours each day on the weekend. Her son, a junior, has it toughest during the winter months, when he plays on a sports team. “Any sport these kids do, the coach will say, ‘If you’re not here all six days, then don’t come at all, you’re not part of the team,’” she says. “How are you supposed to get home from your sport at 8:30, 9:30, quarter to 10 at night and now do five hours of homework?”

Not all parents have the same concerns. John Halligan is a Nutley parent whose oldest son was in the local public school system until eighth grade, then transferred last year to St. Peter’s Prep in Jersey City.

Halligan is impressed with the amount of homework his son has been assigned. “He has about three hours a night and twice that on weekends,” says Halligan, “and I am happy to report that he has done a great job managing everything—which I was a little concerned about. I feel like the homework forces him to embrace the whole process because he has very little time to drift.”

“For every parent like me, there are 10 who are happy with the amount of homework their kids are bringing home,” admits the Bernards Township parent. Part of the reason for the diverging opinions could be that, even among the brightest and hardest-working kids, the speed at which they work can vary significantly, notes Kenneth Goldberg, a psychologist in Haddon Heights and author of The Homework Trap (Wyndmoor Press). Goldberg has three sons, all now young adults. When they were school age, the first two had no problem getting their homework done. It was apparent by second grade, however, that his youngest son was different. “No matter what kind of homework they gave, he was still going to take longer than his friends,” Goldberg says. If his only experience had been with his older kids, he adds, “I would have been the parent clamoring for more homework, not less.”

A really effective homework policy, he notes, would take students’ differing needs and abilities into account. And in fact some schools, including those in Galloway Township, are already doing that. At Benjamin Franklin Middle School, teachers have been asked to let their students know how much time each assignment should take. Students are instructed to stop after the allotted time, leave the remainder for the next day and ask for help. If students find themselves exceeding that limit, they’re supposed to stop at that point and ask for help the following day. “It’s helpful to individual students,” says principal Anthony Orsini, “and if the whole class hasn’t finished their homework on a certain day, teachers know that they’ve either assigned too much or perhaps need to reteach the lesson.”

And then there’s Marilyn Stewart, the head of the Red Oaks School, a independent Montessori school in Morristown. Her homework policy reflects her belief that “homework should be individualized as much as possible.” That doesn’t mean that every child gets a different assignment, but that teachers have the leeway to group students and make assignments according to their capabilities.

Parents and educators looking for an enlightened homework policy might do well to consider the Red Oaks approach, which was designed by Stewart, along with the faculty, when she took the reins as principal in 1999. There’s no homework at all in preschool through kindergarten, and in grades one through three, students get a homework packet on Tuesday that’s due the following Monday and is designed to take about 10 minutes per grade per week. (A first-grader, for example, gets 10 minutes of homework each week; a second-grader, 20 minutes.)

“The reason we’ve done it this way,” says Stewart, “is that a lot of our parents work outside the home. They’re getting home at seven at night, and they don’t have all that much time to read and cuddle and hang out with their kids.” Even students in the upper elementary grades spend only about an hour a day on homework, though they often have long-range individual projects to work on as well. And in the new middle school that Red Oaks opened this year, homework is limited to about 90 minutes a night.

The policy is based on research, says Stewart, citing a 2009 analysis of multiple homework studies published in the APA Educational Psychology Handbook (American Psychological Association).

Researchers found that high school students who regularly completed 7 to 12 hours of homework per week did better on standardized and unit tests than those who were assigned less than 7 hours weekly. More homework than 7 to 12 hours, however, did not correlate to higher scores. In junior high, students who did slightly less than an hour per night scored higher on tests than those who did little to no homework, but those assigned two hours per night actually scored slightly lower than their less-burdened peers. And in the elementary grades, the researchers found no testing benefit whatsoever from homework.

Teachers at Red Oaks also confer with one another about homework assignments so students aren’t deluged on any particular night—something, Stewart notes, that’s easier to do now than ever before. “With technology and the common use of websites for giving out homework, there is no reason that teachers should be unaware of what other teachers are giving,” she says.

Getting the quality of homework right is even more important to Stewart than tweaking the quantity. Homework should help students reinforce skills, especially in math, she says. It should also help them develop independent work skills and a sense of autonomy as learners, especially in the older grades. One thing it should not be is mere busy work. “Endless drill is not a good thing,” Stewart notes. “The research says that you should be varying assignments between short and long, challenging and simple, in order to maintain a level of interest. Because interest is everything.”

Maurice Elias, a Rutgers professor of psychology who has spoken to parent groups in Ridgewood, Millburn and Summit about the need for balance in kids’ lives, believes that too much homework can be harmful “when it negatively affects the love of learning.” A love of learning, of course, may not be accurately measurable by research, but in terms of its contribution to a student’s long-term success, it could be the most important factor of all.

Leslie Garisto Pfaff is a longtime contributor to New Jersey Monthly.