“Is it clean?” Matt asks his teacher.

It’s a question he raises every day about almost everything in his classroom, from doorknobs to desk chairs. He also asks, “Are you sure I can eat that?” and “Can we call my Mom and check?”

Matt (not his real name) starts fourth grade at Brooklake Elementary School in Florham Park this month. His first trip to the hospital came after eating yogurt at 10 months old. Now 10, he is deathly allergic to milk, eggs, soy, tree nuts and legumes, including peanuts. It’s a large swath of the Big Eight—the eight categories of the most common food allergens. These also include fish, shellfish and wheat. Seed allergies are less common, and though Matt outgrew his allergy to sesame, mustard is still a hazard.

Matt’s daily life is rooted in routine. Before he eats lunch, he meticulously washes his hands. At the same time, his designated classroom aide wipes down the cafeteria table where he plans to eat his bagged lunch. The table is a safe distance from the trash cans where carefree peers toss their half-finished milk cartons and peanut butter sandwiches. Before Matt starts computer class, his aide wipes down the screen, the mouse, the keyboard and the table around his workspace. Green signs on the classroom doors declare: “This is an ‘Allergy Free’ Zone. No peanuts, tree nuts, milk, egg, soy, beans, mustard, peas. Your cooperation will help keep our school safe for all our children.” During snack time, Matt eats in the classroom while his classmates enjoy their allergen-rich snacks in the hallway. Matt prefers to eat alone. It’s safer.

Illustration by Ellen Weinstein

These precautions have helped Matt avoid allergic reactions in school. Symptoms of such reactions—wheezing, coughing, watery eyes, hives, inflammation, vomiting, diarrhea—are how the immune system ejects toxins. In the worst cases, the body goes into anaphylactic shock, the technical term for an extreme allergic reaction involving a significant drop in blood pressure, trouble breathing and even death.

According to a 2013 study from the Centers for Disease Control, food allergies among children nearly doubled from 1997 to 2011. One in every 13 children in America has a food allergy.* The increase is not a “frequency illusion” traced to rising awareness. Rather, it is a real, quantifiable jump believed to be caused by modern lifestyle and environmental factors.

The growing frequency of food allergies has significantly altered the classroom experience of an average public school student. As recently as 10 years ago, there were no allergy-conscious rules regulating food; there were no hand sanitizers and disinfectant wipes in every classroom.

“Kids didn’t have these problems when I was young,” says Tracy, mom of Alex (not their real names), a Hudson county first-grader who is allergic to peanuts, tree nuts, sesame and soy. “I think some people still don’t take it seriously. They have to understand that kids have died from this. It’s not moms whining and whatever; their poor, innocent kids could die just from enjoying a treat.”

In 2008, of the approximately 300,000 New Jerseyans with food allergies, one-third were children. That year, the New Jersey Department of Education released guidelines for the management of life-threatening food allergies in schools. Districts enact the procedures based on the needs of specific students. New Jersey was one of 15 states to publish food-allergy procedures before the federal government established guidelines in 2013.

“Kids didn’t have these problems when I was young.”

Because of these procedures, many elementary schools in the state now ban sharing of food among peers on school property. They also do not allow food to be used as rewards or goody-bag stuffers on holidays like Halloween and Valentine’s Day. (Nationally, the advocacy group Food Allergy Research & Education—or FARE—promotes the Teal Pumpkin Project, where houses with teal-painted pumpkins hand out non-food treats on Halloween like glow sticks, whistles and playing cards.)

Matt’s teacher rewards students who perform well with non-food incentives such as colorful stickers, erasers and pencils. For birthday parties and in-classroom celebrations at Brooklake, there’s a strict five-item approved snack list that parents of third-graders are allowed to send to school: water, Skinny Pop popcorn, Silly Swirl ice pops, Dum Dum lollipops and Florham Park Pizza. Other districts, including nearby Chatham, have a stricter approach, with mandatory no-food celebrations. Holidays are for games and card exchanges instead of another opportunity to snack.

Even though Matt is allergic to milk and eggs, his mom, Alita, did not object to pizza on the approved list. “I didn’t want to be the party pooper,” says Alita. “I even went to the principal and said, ‘He has so many limitations—what are you going to give him, air sandwiches?’” She feels that, at this point, Matt is old enough to understand that he can’t eat pizza.

“As children get older, they can advocate for themselves better,” says Alita, who ran for the Board of Education a few years ago to speak up for students with food allergies. Inspired by a program at a Chatham elementary school, Alita and other parents went to Brooklake’s principal and proposed starting a support group for kids with allergies. Known as Brooklake Food Allergy Support Team (FAST), the group meets once a month during lunch in a classroom that is sanitized by an aide beforehand.

Aides like Matt’s are often included in the confidential plan parents work out with the public school to accommodate a student with special needs (in some cases required under Section 504 of the Americans with Disabilities Act). The district assumes all costs of the accommodations, including the cost of the aide. Matt’s aide and teacher are delegates, meaning they can administer injectable epinephrine, typically under the brand name EpiPen, to stop anaphylactic shock. (There is no suitable generic for the EpiPen, which dominates the market and can cost up to $600 after insurance.) All delegates throughout the school have a roster of Brooklake’s students with allergies, along with the seemingly innocuous foods they are allergic to, such as partially cooked eggs and tofu.

“What are you going to give him, air sandwiches?”

Renee Wickersty, supervisor of health services for the 22 schools in the Camden City school district, says every nurse and security guard in the district is able to administer EpiPens. As of last year, all 78 security guards were cleared to administer EpiPens even to students not formally recognized as having food allergies. Along with emergency codes for fire drills and active shooters, schools now have codes for anaphylactic episodes.

Philadelphia-based food-service giant Aramark, concessionaire for Camden and 24 other districts in the state, does not serve anything in the cafeteria containing peanuts, tree nuts or pork. But that’s not enough of a control for the district to label itself “peanut free.” “There is a limit to how much we can really do,” says Wickersty. “How do you monitor 11,000 students, plus staff, plus families? We can’t. That’s not going to happen. That’s one issue. The other issue is you can have a child who will only eat peanut butter. So how is it fair to him or her to not have the peanut butter?”

If a parent wants a child’s school to have a peanut-free table in the lunchroom, the district will accommodate the request, but it’s not a mandatory fixture. The district tries to always have a meal substitute available when a student with allergies punches in his or her ID number in the lunch line.

Sal Valenza, food-service director for the West New York school district in Hudson County and former president of the New Jersey School Nutrition Association, says his district opts not to offer food that contains peanuts. West New York and hundreds of other New Jersey districts use a menu app called NutriSlice, which shows the lunch menu for the upcoming month, denoting when allergens like soy, egg and wheat are among the ingredients. Parents use the app to customize meals based on their child’s dietary needs. Low-tech school menus use the letters W, S, D and E to denote when a meal includes wheat, soy, dairy or eggs.

Wheat is another issue for school diets. Charlie, a fifth-grader at Clinton Elementary School in Maplewood, was diagnosed with celiac disease, an autoimmune disease, when she was in second grade. For those with celiac disease, foods with gluten (a protein found in wheat, barley, oats, rye, malt and spelt) damage the lining of the small intestine, causing a range of digestive and neurological symptoms, including bloating, migraines and seizures.

Before Charlie was diagnosed, she never liked the “kid food” served in schools because it made her sick. “Everything we feed our kids—chicken fingers, pizza, pasta, mac and cheese,” says Charlie’s mom, Martha, “it’s all gluten.” Since snacks containing nuts are banned at Clinton Elementary, Martha sends treats like corn chips, Skittles and Junior Mints. “Her favorite candy bar is a Baby Ruth, and I obviously can’t send that to school.” Out of the 80-plus kids in the fourth grade, Charlie was the only gluten-free student. Luckily, the class parents have been supportive. Martha receives calls from class moms asking for Charlie’s favorite gluten-free foods to prepare for birthday celebrations. “It makes me so happy,” she says. Charlie even took an after-school cupcake-decorating class—and gave her finished treats to her younger sister.

“Everything we feed our kids—chicken fingers, pizza, pasta, mac and cheese—it’s all gluten.”

Remarkably, celiac disease is now four times as common in America as it was 50 years ago. Why has food reactivity increased so sharply in recent decades?

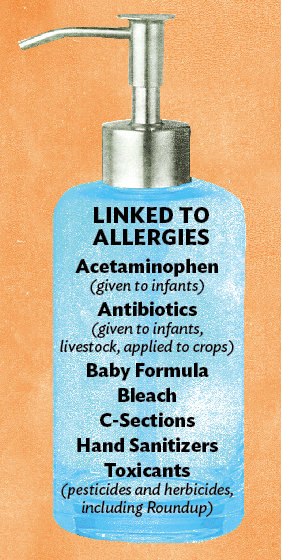

Dr. Maya Shetreat-Klein, a pediatric neurologist and author of The Dirt Cure (Atria Books, 2016), says there are two main reasons. First, mass-produced food is modified in ways that eliminate beneficial nutrients and add harmful chemicals. American white flour, for example, is treated with chlorine bleach and sprayed with fungal amylase and potassium bromate to prolong shelf life. Peanuts—which were traditionally boiled, fried or eaten raw—now are almost always dry roasted, especially when used in processed foods, because it’s a quick way to create that sweet caramelized flavor. However, dry roasting creates harmful proteins known as advanced glycation end products, which have been linked to many debilitating conditions, including allergic reactions, diabetes and even Alzheimer’s disease.

It’s not just how foods are prepared; it’s also how they are grown. A 2013 study connected the increase of celiac disease to eating foods sprayed with the ubiquitous weed killer Roundup.

Illustration by Ellen Weinstein

Second, studies indicate that children with compromised guts and immune systems struggle to adapt to their environment, causing their bodies to misidentify benign foods as harmful. According to what’s known as the hygiene hypothesis (or the microbial exposure hypothesis), a childhood spent largely indoors with significant exposure to bleach, antibacterial wipes and hand sanitizers leaves a young immune system confused and ill-prepared to process good bacteria. (On September 2, after this story went to print, the FDA announced a ban on marketing antibacterial soap for these reasons, among others.**) Throughout history, some theorists note, children who lived in villages have fallen ill during hay-fever outbreaks, while children on farms have stayed healthy. Today, children who live in proximity to livestock and are regularly exposed to microbes have fewer allergies than their urban and suburban counterparts. (It’s another reason why eating local, or better yet, from backyard gardens, is a step in the right direction, says Shetreat-Klein.)

The hygiene hypothesis also implicates our modern desire for quick pharmaceutical fixes. Studies show that infants given antibiotics and acetaminophen are more prone to develop food allergies and other chronic diseases. Fever is the body’s response to infection—a kind of natural antibiotic—so an infant’s immune system is handicapped by these medications, causing it to mislabel harmless foods as noxious. “If that’s one of the theories,” says Alex’s mom, Tracy, “my son was on [antibiotics] a few times because he had sinus infections as a baby.”

Additional research ties the increase in childhood food allergies to the prevalence of Cesarean sections. In New Jersey, C-sections increased from 23 percent of live births in 1990 to 37 percent in 2014. An unintended consequence of C-sections is that babies who are pulled through the abdomen miss the important vaginal microbial baths experienced by babies that pass through the birth canal. Mothers are also given antibiotics before the surgery, which pass to the child in utero. Studies suggest that giving probiotics to C-section babies starting after birth to six months may help reduce the incidence of allergies. The use of formula instead of breast-feeding is also believed to stunt a baby’s immune system.

As this fragile 21st-century generation matures, colleges and workplaces may one day have to institute restrictive food policies similar to elementary schools. In the meantime, parents of allergic children carry the burden of preparing safe foods and advocating for safe student environments. “It’s a bit limiting,” says Tracy, who makes lunch every day for Alex. “But it’s better than worrying.”

*The print version stated one in every 25 children has a food allergy. We have updated the statistic accordingly based on information from Food Allergy Research & Education.

**Added after FDA announced triclosan ban on September 2.