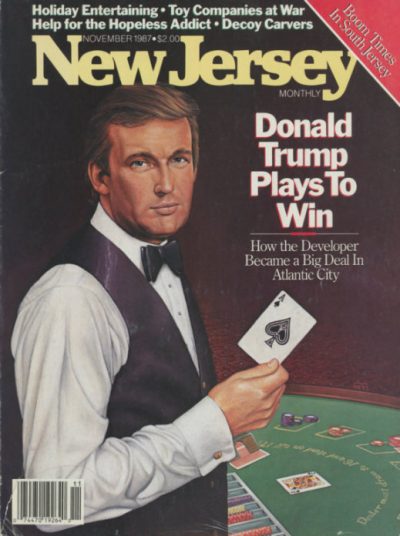

Editor’s Note: This story first appeared in the November 1987 issue of New Jersey Monthly. At the time, Donald Trump already had two casino hotels in Atlantic City—Trump Plaza and Trump Castle (later Trump Marina)—and had just taken over construction of the unfinished behemoth, the Taj Mahal. Public response ranged from hopeful to skeptical, as the city’s residents, politicians and investors pondered Trump’s dedication to the ailing community. The Trump Taj Mahal finally opened in 1990. The property filed for bankruptcy by 1991. In the years that followed, Trump consolidated his three Atlantic City casinos under a publicly traded company, Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts. In 2004, the entity filed for bankruptcy with $1.8 billion in debt. Trump Marina was sold in 2011; it is now the Golden Nugget. Trump Plaza closed for good in 2014. The Trump Taj Mahal is now owned by Carl Icahn.

When Donald Trump and Jack Davis, the president of Resorts International, met on the slopes of Aspen for a ski vacation last Christmas, Wall Street mavens knew something significant was afoot. Throughout the fall of 1986, Trump, the voracious real-estate magnate, had been trying to expand his casino holdings. Davis, meanwhile, was casting about for a buyer for his $750-million casino/hotel empire. Like an errant skier, the company had been speeding downhill and out of control since the death of its visionary founder, James Crosby, eight months earlier.

As they rode the chairlifts, Davis made no attempt to gloss over the company’s predicament: Someone was needed to rescue Resorts, he told Trump. The Taj Mahal, a $800-million casino/hotel/entertainment “fantasy” on the Boardwalk, had the potential to be the most exciting phenomenon to hit Atlantic City since gambling was legalized in 1978. But the project was plagued by cost overruns and construction delays—and at the rate things were going, it might remain a fantasy forever. Crosby’s family, led by brother-in-law Harry Murphy, who had inherited Resorts after the chairman’s fatal heart attack in April, were in over their heads, he implied. Trump had the credibility, the credit, the trust of Wall Street—would he be interested in purchasing voting control of the company from the family for $110 million?

Trump jetted back to his New York City headquarters just after New Year’s, mulling over Davis’s proposal. The offer was an intriguing one, to say the least: On the downside, Trump would have to raise at least another $500 million to complete the Taj Mahal—and who knew whether the stagnant gaming industry could absorb 1,260 more hotel rooms and a 120,000-square-foot casino. On the up side, the purchase of Resorts would make Trump far and away the dominant power broker in Atlantic City. And there was another consideration: During the speculation-mad seventies, James Crosby had bought nearly half of the vacant real estate in town. The possibilities for its exploitation could be endless if Trump owned it.

Weeks after the schussing, Trump made up his mind. In January, he agreed to purchase, at $135 a share, about 580,000 shares of Resorts “B” stock (with 100 times the voting power of the “A” shares) from the family and the estate of Crosby—effectively giving him 93 percent voting control of the company. In the boardroom of Resorts International and on Wall Street, the takeover was greeted with a sigh of relief. In the political hangouts of Atlantic City and the executive suites of Trump’s casino competitors, meanwhile, the mood ranged from hope to darkest trepidation.

Six months later, Donald Trump, developer nonpareil, leans back in a leather chair in his 26th-floor penthouse atop Trump Tower, framed by the Plaza Hotel and the verdant expanse of Central Park. Sipping a breakfast glass of tomato juice, the cherubic-looking magnate is expounding with his usual tinge of self-satisfaction upon the latest addition to his ever-expanding domain. “The deal had to be done,” he says. “If the person who would have gotten Resorts had been negative for Atlantic City, that would have been terrible for me and for everyone else in this town.”

Sipping a breakfast glass of tomato juice, the cherubic-looking magnate is expounding with his usual tinge of self-satisfaction upon the latest addition to his ever-expanding domain.

He swivels in his chair, glancing out the window at midtown Manhattan like a czar surveying his empire. “Ten years down the line,” he claims, “Atlantic City is going to be a truly great place. You’ll see a cleaned-up, beautiful seaside town, with new housing for the poor and middle class, and open space. In a decade, Atlantic City is going to shock and surprise a lot of people.”

When Trump talks about his vision of Atlantic City these days, one is tempted to believe him. After all, at 41, the developer has long since established himself as a man with an ability to turn grandiose ideas into steel-and-glass realities. Trump Tower on Fifth Avenue and the Grand Hyatt next to Grand Central Station have cast him as the quintessential symbol of opulence and power, Manhattan-style. His completion of Wollman Skating Rink in Central Park in six months, after the Koch Administration had fumbled for years, made him the darling of the city and enhanced his reputation as a miracle worker. And the Queens-born, University of Pennsylvania educated scion of 83-year-old developer Fred Trump hasn’t exactly shied away from the limelight: With glossy magazine spreads showing off his 110-room mansion, Mar-a-Lago, in Palm Beach, with his fashion-plate wife, Ivana, a former model and Olympic skier, at his side, Trump happily cultivates the image of a kinetic Adonis whose noblesse oblige outdoes anyone seen on Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

In Atlantic City, the developer has been similarly blessed with the Midas touch. His purchase of Resorts has capped one of the most extraordinary successes in the history of American real estate: Since 1982, he has maneuvered his way into total ownership of two casinos (Trump Plaza on the Boardwalk and Trump’s Castle at the Marina across town), premier name recognition in town, and gambling profits of $16 million in 1986. Buying and selling of stock in Holiday Corporation, Bally, and Allegis dropped $122 million into his bank account. That was more than enough to cover the price he paid for Resorts International.

“Ten years down the line,” he claims, “Atlantic City is going to be a truly great place. You’ll see a cleaned-up, beautiful seaside town, with new housing for the poor and middle class, and open space. In a decade, Atlantic City is going to shock and surprise a lot of people.”

Indeed, Trump seems intent on making Atlantic City a fiefdom for his family. His wife, Ivana, serves as chief executive officer of Trump’s Castle and spends several days a week there; his brother Robert sits on the executive committee of Trump Plaza and Trump’s Castle and is a vice chairman of Resorts International.

“Donald always wanted to be the best at everything, and Atlantic City is giving him that opportunity,” says Al Glasgow, a Trump consultant and the editor of Atlantic City Action, an industry newsletter. “He likes hotels, he likes glamour, and he likes the high volume of the casino business. He proved he could come into an industry he knew nothing about and become the dominant player in three years.”

Still, questions persist about the level of Trump’s commitment to anything beyond the enhancement of his own ego. In New York, the Trump Organization has battled a barrage of tenant lawsuits charging everything from racial discrimination to harassment. In Atlantic City, he’s acted more like a precocious kid at the Monopoly board, hungrily acquiring pieces of property for the pure joy of besting his competitors. Casino-industry watchers say his tactics have been typified by litigation, stalling, and all-around predatory ruthlessness. Casino Control Commission chairman Thomas Read chastised Trump at a licensing hearing this year for reneging on obligations to improve the Atlantic City infrastructure.

Naturally, many people are skeptical about what Trump will do with the hundreds of fallow acres that came under his control with the purchase of Resorts International. Although he has the opportunity to play a decisive role in revitalizing the city beyond the Boardwalk—to become, in short, the Robert Moses of the South Jersey Shore—he can also choose to sit back and do nothing, maintaining the shabby status quo.

“The city is split into two camps about him,” says city councilman Jim Whelan. “One side says that Trump is going to be the best thing that ever happened to Atlantic City, replacing the inertia of Resorts’ last few years with new energy and vision. The other side says Trump will own this town lock, stock, and barrel; that he’ll be able to tie things up as long as he wants.”

In Atlantic City, Trump acted more like a precocious kid at the Monopoly board, hungrily acquiring pieces of property for the pure joy of besting his competitors.

Whatever Trump decides to do, his actions will be largely determined by two important factors; the precarious health of Resorts and the endemic plight of the surrounding neighborhoods. When Donald Trump took over Resorts International last March, he inherited a company with a morass of problems: Its leadership had alienated many city politicians through tax disputes and neglect of its development obligations; the Taj Mahal was sucking up hundreds of millions of dollars with no end in sight; and the Southern Inlet, a Resorts-owned neighborhood just north of the Taj Mahal, was looking like Dresden after its firebombing in World War II.

The decline of the Inlet was perhaps the most tragic of Crosby’s legacies. Back in 1976, when James Crosby wagered more than $40 million to buy and renovate the old Haddon Hall Hotel on the Boardwalk, he envisioned that gambling would transform the crumbling town into a veritable Emerald City-By-the-Sea. In one respect, he was right: the Resorts International casino, which beat out all the competitors in just eight months, turned Crosby’s tiny company into a $439 million-a-year symbol of glitz and glamour. It also served as the vanguard for a new industry that eventually brought 30 million visitors a year to the city, along with 40,000 jobs, 8,000 hotel rooms, and gaming revenues of $2.28 billion a year.

But the casino profits never trickled down to the city’s underclass. Land speculators snapped up acreage around the Boardwalk and beyond at exorbitant prices, driving up rents and property taxes, forcing a mass exodus of the poor. James Crosby was one of the most voracious of the land accumulators. In 1976, he spent $5.5 million for a 56-acre tract of urban development land next door to Haddon Hall (it would become the site of both Taj Mahal and the newly opened Showboat casino). Later, he scooped up the 100-acre Great Island and bits and pieces of the Inlet down the Boardwalk from the Taj.

“Jim Crosby had the philosophy that Resorts should own all the land around the Taj Mahal, and then we could see that it was developed. But he was talking 50 years down the line,” says Jack Davis, who worked for Crosby since the fifties, when Resorts was a tiny enterprise called the Mary Carter Paint Company. “We bought far more than we could ever possibly use.”

Some experts called the Inlet one of the worst examples of urban blight in the entire country. Weed-choked, garbage-strewn lots extend half a mile inward from the ocean. Scattered about are boarded up townhouses, lone sentries gazing out over an eerily deserted landscape. A handful of black and Hispanic squatters continue to live amid the hulks of buildings. The only other movement comes from a few seagulls soaring over the wreckage, searching futilely for something worth scavenging.

The Trump Taj Mahal finally opened its doors in April 1990. Michael Jackson performed at the opening ceremony. Courtesy of Trump Entertainment Resorts

To be fair, not all the blame for the stagnation belongs to land accumulators such as Crosby. “Even if Crosby wanted to sell, who was gonna buy his land?” asks Marvin B. Roffman, an analyst with Janney Montgomery Scott in Philadelphia. “Restaurants closed, businesses weren’t clamoring to come into the area, because anybody who wanted to buy clothing, jewelry, or anything else would go into the casinos. And since you didn’t have the ancillary businesses to support a thriving community, people didn’t want to move in. But you couldn’t bring in businesses where you had no people.”

Even so, heightening Resorts’ sense of inertia were Crosby’s troubles with the Taj Mahal, which he began constructing on the urban development tract in 1982. The 54-year-old entrepreneur was a man of vision, but he knew nothing about building. His waffling plans for the Taj quickly made Shah Jahan’s expenditures on the original seem modest by comparison. As the costs soared—$125 million, $300 million, $500 million—the emphysema-ridden chairman retreated to his wheelchair in his ninth-floor seaside penthouse at Haddon Hall, breathing bottled oxygen, absorbed by his mounting stake in Pan Am and a takeover bid for TWA, and growing increasingly detached from day-to-day operations. A sense of malaise hung in the briny air.

“Once Davis and I were sitting in his office, and Jack asked me, ‘What’s wrong here?'” Glasgow remembers. “I said, ‘We’re on the fourteenth floor, they’re shooting craps on the first floor, and Crosby’s in the next office playing the poor man’s Howard Hughes.'”

In April 1986, the chain-smoking Crosby died while undergoing lung surgery, leaving Resorts in disarray. The chairman’s brother-in-law, Henry Murphy, a Trenton undertaker who knew as much about running a casino as Crosby knew about embalming, was elected chairman of the board. As Resorts stock soared in expectation of a takeover, the Murphy/Crosby clan spent months debating whether to sell their controlling stock or engineer some scheme—an Employee Stock Ownership Plan, a recapitalization—to retain control. When Donald Trump emerged as a white knight, the rescue came just in time.

Donald Trump’s rise in Atlantic City neatly paralleled Jim Crosby’s decline. He made his first move in the city quietly; in the early eighties, he bought adjoining plots of land near the Convention Center on the southern end of the Boardwalk at a time when virtually no one had heard of him. Trump systematically accumulated the pieces of a casino empire—and he wasn’t afraid to step on a few toes in the process. His first move was to negotiate a joint partnership with Harrah’s/Holiday Inn to erect a casino/hotel on his Boardwalk property. For Trump, it was irresistible, risk-free deal: Harrah’s paid Trump a $30-million profit, put up $250 million to finance the casino, agreed to manage the property for free, and indemnified Trump against all operating losses for five years.

The good relations lasted about five minutes. Trump, who has never been noted for his humility, forced a series of name changes: from Harrah’s Boardwalk Casino Hotel, to Harrah’s at Trump Plaza, and then just plain Trump Plaza. He also stalled on his responsibility to build a 1,700-car parking garage adjacent to the casino, then sued Harrah’s for “incompetent management” because not enough customers were driving to the place. By the time Harrah’s sold out to Trump for $73 million, the two sides had gone from amicable partners to bitter enemies. “We had a long and disharmonious relationship with Donald Trump that is now settled,” is all a Holiday Inn spokesman will say about the feud. “We’re not into trading public accusations.”

A few months later, Trump acquired Baron Hilton’s hotel/casino on the Atlantic City Marina in a smoother war. Hilton had nearly completed the project when the New Jersey Casino Control Commission rejected his license application, citing the company’s involvement with a Chicago mob lawyer. Hilton sold out to Trump for $320 million, turning down a comparable bid from Trump’s flamboyant competitor, Steve Wynn of the Golden Nugget.

Last year, Trump’s insatiable appetite began acting up again. Hungry to expand his casino empire into Nevada, Trump began buying up stock in both the Holiday Corporation (owner of Harrah’s) and Bally. But Holiday, his old enemy, thwarted him by taking on massive debt in a recapitalization scheme; Trump bought a 4.9 percent stake on the open market for a $30-million-plus profit. Bally made itself equally unattractive to the raider by purchasing Wynn’s Golden Nugget casino on the Boardwalk for $430 million. Trump promptly sold back his 4.9 percent stake for another $31.7-million profit. The rapid-fire buying and selling cast Trump in the guise of a corporate raider looking for easy money. But Trump insists he was looking for a long-term investment. Then along came Davis.

“When I talked to Donald in November, he was very lukewarm on Resorts,” says Dan Lee. “He was much more interested in Holiday’s Tahoe resort and Bally’s Reno and Las Vegas casinos. He didn’t like the fact that Resorts had both B and A stock and that the A was way overpriced. He didn’t care about Paradise Island [Crosby’s casino in the Bahamas]. He hasn’t even visited the place yet. What finally turned him around was the Taj Mahal… In effect, this place is twice the size of any existing casino in Atlantic City. If you’re going to have a very large new competitor come into town and outdo your prices, then why not buy it?”

Today, the sounds of pneumatic drills, hydraulic pumps, bulldozers, cranes, hammers, and saws drift over North Carolina Avenue—music to the ears of Jack Davis and the other Resorts executives ensconced on the fourteenth floor of Haddon Hall. On the Boardwalk, crowds of gamblers promenade past a long wooden barrier that stands before a massive skeletal structure of concrete blocks and steel girders.

By next summer—God and Atlantic City labor unions willing—those girders should become a completed casino/convention hall/sports arena drawing thousands of gamblers around the clock. Signs in front of the low-rise and the 42-story tower behind it breathlessly promise:

“THE WONDER OF THE GAMBLING WORLD… A THEMED, LAVISHLY DECORATED CASINO… 1,257 SPACIOUS ROOMS AND SUITES… 9 SUPERB RESTAURANTS SPANNING THE GLOBE… THE WORLD’S TOTAL ENTERTAINMENT COMPLEX…. 225,000 SQUARE FEET OF MEETING AND EXHIBITION SPACE… A BILLION DOLLAR FANTASY!”

The mood, to say the least, is nothing short of exuberance at Resorts International these days. With Trump newly installed as the chairman of the board, the Wall Street investment community is apparently convinced that, unlike Crosby, he can bring the Taj Mahal in on time and within its $800-million budget. Indeed, no less lofty a banking house than Drexel Burnham Lambert recently fought hard to do the junk-bond financing for Resorts, although the firm had to pull out for conflict-of-interest reasons when Trump bought a 4.9 percent stake in Golden Nugget, part-owned by another Drexel client, Wynn. Bear Stearns, Trump’s longtime investment banker, is now underwriting the project.

“The most important element for Resorts International for the next year and a half is construction,” says Trump. “I don’t even look at it as a casino company until 1989. Resorts needs somebody that, one, knows how to build; two, has very good relationships on Wall Street so that the money can be funded; three, is a hotel/casino operator. And probably in that order.”

“Trump Plaza is probably the most successful hotel in Atlantic City, and when I took over from Harrah’s it was in the ninth place,” he gloats. “Trump’s Castle was the most profitable hotel in the first quarter of this year. I don’t think there are two hotels anywhere that are run better or cleaner… I’m confident that the Taj is going to be truly fantastic.”

The Trump Taj Mahal filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1991. The deal caused Trump to give up half his personal stake in the casino, and he sold his yacht and airline. Courtesy of Flickr/Bahman

Still, some casino analysts are skeptical that the Taj can ever make back its investment. They point to a slowdown of gambling growth in Atlantic City and the fact that Caesars, Bally, and other big guns are hardly going to sit passively and watch the Taj steal their share of the market. “It’s going to have to gross $1 million a day for Resorts to recoup its investment,” says Glasgow. “And no casino in Atlantic City has ever performed that well.”

“I’m confident that the Taj is going to be truly fantastic.”

But Glasgow and others point out that Trump’s financial stake is minimal. Despite having voting control, he owns less than 10 percent of Resorts International and he isn’t putting up his own money to finance the Taj Mahal. “What’s really at risk is Donald’s reputation,” Glasgow says. “He’s putting his name on the line here.”

Even if Trump finishes the Taj Mahal on schedule, his problems are by no means over. New Jersey Casino Commission regulations stipulate that no one can own more than three casinos in Atlantic City. And that means Trump, who already has two licenses, can’t run both the Resorts I and the Taj Mahal. Trump says he might close down the old gaming room at Resorts but keep its 700-room hotel open to service the Taj. “But if you were a shareholder, you might have problems with Trump’s decision to close Resorts I,” says Read. “Trump could find himself battling stockholder lawsuits.”

The alternative is to sell off the old casino/hotel, whose sedate, 1920’s charm contrasts with Trump’s own preference for gilded opulence—the atriums and neo-modernistic flash of the Portman-designed Trump Tower, for example. “But who’s going to buy it?” asks Dan Lee. “Do you want to buy a 60-year-old hotel that’s been converted into a casino, six months before a place opens next door that’s twice as big, twice as gaudy, and a lot more efficiently designed? That’s like buying the Hudson River Ferry Terminal just before the Lincoln Tunnel opens.”

For the city’s politicians and community leaders, the most burning issue is Trump’s commitment to the surrounding territory. At Trump’s licensing hearing before the Casino Control Commission last spring, for instance, chairman Read made very clear that Resorts’ obligations to the city included a 1,200-unit, low and moderate-income apartment complex on the urban development tract and that he expected Trump to make good—unlike in the past. “I mentioned the fact that when Trump bought the Hilton property, Hilton had agreed to make improvements on the Marina roadway in front of the casino, but Trump testified he wasn’t aware of Hilton’s obligations,” says Read. “I didn’t think it was appropriate for the same thing to happen with Resorts’ property.”

Trump is clearly anxious not to roil the political waters this early in the game. To show his good intentions, he recently hired Alex Cooper, the planner and architect of Manhattan’s Battery Park City, to draw up plans for the development, which will rise directly behind the Taj Mahal. “I think you’re going to see something that will be spectacular,” Trump says with his customary understatement.

“I think you’re going to see something that will be spectacular,” Trump says with his customary understatement.

John McAvaddy, president of the Atlantic City Housing Authority, has met twice with Trump and his brother Robert since the Resorts buy-out. He says he’s confident that Trump will speed along construction for lower- and middle-income tenants on the 27 vacant acres that will remain on the tract after the 1,200-unit complex is done. “The city never really trusted Resorts during Crosby’s years,” McAvaddy admits. “The company never presented a total development plan for the tract. And they reneged on their tax obligations to the tune of several million dollars a year. Hopefully, Trump’s coming in will change Resorts’ old image.”

Unlike the urban development tract, however, Trump has no obligation to the city to develop his holdings in the Inlet. Indeed, he could continue to let the property rot in the salty Atlantic breeze just as Crosby did, but he’s already put 800 acres up for sale.

By 1992, the Trump Plaza Hotel filed for bankruptcy, causing Trump to relinquish 49 percent stake in the Plaza to lenders. Courtesy of Flickr/Lisa Andres

Trump’s arrival comes at an auspicious time for an area whose population has dwindled to about 250 Hispanic families at the bottom of the economic ladder. For the first time in years, thanks to the coordinated planning of the city and county governments and the Casino Reinvestment Development Authority (CRDA), which directs 2 percent of the casinos’ gross revenues toward neighborhood rehabilitation, the Inlet has begun to show stirrings of life. “In the past, those CRDA funds were diluted in minor rehab and social programs spread all throughout town,” says McAvaddy. “Now, we’re targeting the Inlet. And for the first time, there’s a unification of effort among the governing agencies in town and developers.”

For example, senior citizen housing, low-income projects, and condominiums have sprung up in the past twelve months. This spring, Harrah’s proposed a $44-million, 600-unit, three-block low-rise apartment complex in the northern corner of the Inlet—partly, some say, to take the gloss off Trump. “They don’t want people thinking ‘Atlantic City—Trump,'” says one city councilman. “How do they do that? A major residential developer geared to secondary homes for the New York market.” Caesars has also committed $34 million to a 230-unit low- and moderate-income high-rise. McAvaddy is confident that once Harrah’s and Caesars break ground, “developers will be standing in line. Something is definitely going to happen.”

Indeed, the mini-renaissance may provide Trump with the buyer’s market Resorts has been waiting for. “A lot of land owned by Resorts—such as the south Inlet—is a detriment to other people who want to develop,” he says, “and we’re going to put it up for sale.” The city government is considering changing the zoning for much of the land, which was originally set aside for casino development, to spur residential building. In late August, Trump, Alex Cooper, and Trump’s housing director, Tony Gleiden, met city and county leaders to discuss proposals for the Inlet, and many politicians came away convinced that Trump’s intentions were honorable.

“Trump sees that he has both a moral obligation to the community and a need to protect his own investments,” says McAvaddy. “My personal guess it that Trump will go forward and try to stir housing construction,” says Read. “It may be from a selfish point of view. If you’ve got a vibrant city out there, it will help the casino business.”

But Councilman Harold Mossee, who district includes the Inlet, is skeptical that any of this activity will help Atlantic City’s poor. “Trump has made grandiose statements about aiding the needy but he adds a corollary, ‘[It will happen] when I complete the Taj Mahal and it starts paying for itself.’ But that may take 99 years. Trump is, in essence, saying he has no intention of doing anything.”

Mossee discounts the benefits of Resorts’ 1,200-unit project next to the Taj Mahal, saying its $850- to $900-rent range is out of the reach of low-income families. What he would like to see is aggressive renovation of the roughly 200 buildings, many abandoned, that Resorts owns. “If Trump said, ‘We’re going to spend $20,000 on each building,’ they could get three quality apartments in each building. Most working people would be eager to live in a place like that.”

But so far Mossee says he has seen no signs of Trump’s good faith. “He’s a very flamboyant, charismatic liar,” Mossee contends. “He has to prove me wrong.”

Councilman Jim Whelan also cautions against placing too much hope in Trump alone. “The real danger is ascribing to anyone the ‘savior’ role,” he says. “We went through this a number of times with the casino referendum, the act, and the opening, and none has been the single catalytic event to turn things around. The rebirth of this town is going to depend on a lot of people acting together.”

“He’s a very flamboyant, charismatic liar,” Mossee contends. “He has to prove me wrong.”

But many Atlantic City residents say they believe that Trump will be the all-important catalyst to spur an urban rebirth. On Congress Avenue, in the heart of the south Inlet, Dominick DeJoseph considers the prospects as he sits on the porch of his two-story red brick townhouse, the last survivor on a street that looks as if it recently served as a testing ground for a convention of demolition experts. DeJoseph, a retired electrical worker from Philadelphia, has summered in Atlantic City wife his wife, Gilda, for the past 30 years. He has seen the neighborhood decline from a lively, middle-class Jewish enclave to a burned-out ghost town.

“Twenty years ago, you had beautiful new row houses, apartment buildings, the St. Charles Place Hotel, the Breakers right over there on the Boardwalk,” he says, flashing a near-toothless smile that mirrors the condition of his block. His 60-year-old row house on Congress Street juts out alone, surrounded by rubble-strewn lots. “Things started to slide just before the casinos moved in. Then Resorts started buying the property, tearing down decrepit buildings. We were offered $100,000 to sell out, but we turned ’em down. This is our home. We’ll never sell it.”

Waves crash over the empty beach a block away. Seagulls cry overhead. The white-haired man gestures toward the tower of the Taj Mahal, visible just past the Showboat casino a few blocks south. “I don’t think it’s right that Resorts should own this goddamn property and have it lying around here like this,” he says. “The city should force ’em to do something with it…. But that Trump—he’s a big entrepreneur from New York. And he might come in and do something with all this. He might just build this place back up to what it once was.”

Joshua Hammer writes frequently about business. His articles have appeared in Esquire, Manhattan, Inc., and GQ.

All that made sense when AC was the only east coast place for gaming. Casinos popping up like weeds put an end to any hope for an AV recovery (actually legal gambling everywhere has killed AC). What is amazing is that there were a good 20+ years of solid business with no local competition and precious little in the form of neighborhood redevelopment came about. Somewhat similar to how huge sports arenas are promoted as community revenue generators when they are not.