Editor’s note: This interview was conducted before the postponement of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band’s 2023 tour, due to Springsteen being treated for peptic ulcer disease. The tour is currently slated to resume in March 2024.

Steve Van Zandt declared him “E Street’s secret weapon.” Rolling Stone christened him “a miracle.” But on stages around the world, he answers simply to Boss Bruce Springsteen’s affectionate “Jakey!”

Jake Clemons officially joined the E Street Band in 2012, following the 2011 death of his predecessor and beloved uncle, Clarence Clemons. His soulful saxophone, equal parts reverent and soaring, is an essential ingredient of the band—as is his desire to be a conduit for connection and transcendence.

Ahead of his October 21 solo concert at the Stone Pony, Clemons chatted with New Jersey Monthly about early Asbury Park memories, Clarence’s influence, and why live music creates a “sanctuary” wherever you are.

[RELATED: Steven Van Zandt on Springsteen, ‘The Sopranos’ and Shrugging off Stardom]

The Jake Clemons Band returns to the Stone Pony on October 21. What are some of your early memories of playing the venue or the Jersey Shore in general?

The first time I played the Jersey Shore that I can remember, I believe it was 1999. I was 19, on tour with a band from out West. We actually played the Saint, which was a tiny little club [in Asbury Park]. But even then, the Stone Pony held that legendary status. And it was something that you would dream to get to at one point.

I think the first show that I saw [at the Stone Pony] was actually Clarence. He played there and recorded Live in Asbury Park. It was on the Summer Stage outside, and just an epic night. And [about a decade] later, I was there fronting my own band.

I’ve played there many times since then. And funnily enough, it’s grown on me more over time. Sometimes venues get tired, but [the Stone Pony has] become more of a place that I love to go back to.

They take music seriously. They have an incredible crew. The sound is phenomenal. And [the music] sounds bigger than it should for the space that it is. So it’s really precious as a venue for artists, and I think for fans as well.

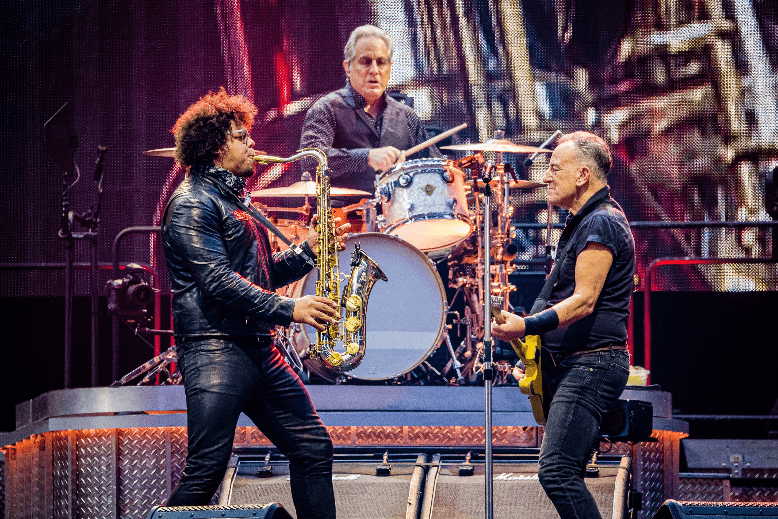

Live music is “part of the narrative of our human soul,” Clemons says. Photo: Courtesy of Tara Keane Photography

You’re known for engaging in very personal, meaningful connections with your fans and audience. Nearly a decade ago now, you even did a series of shows in people’s living rooms. And you’ve since said that such a tiny, intimate setting can actually contain the same intensity as a stadium.

The living-room shows were some of the most precious experiences I’ve ever had. It’s really important for me to be able to get close to the audience whenever I can. That’s a part of humanity that I celebrate. That connection is everything, you know? Without that, why would I ever leave the studio? [Laughs.] I’m passionate about it, I absolutely love it, and it’s important to me.

There’s something about the live-music experience that’s ancient. It’s a part of the narrative of our human soul, I think. I remember reflecting when I was doing those smaller shows in people’s homes, thinking, This must be similar to how it felt [back when we lived in caves], you know? This little sanctuary, where people are all gathered together in a living space, making something beautiful and precious together. And that just extends to a larger stage like the Stone Pony, and then to a larger stage like MetLife Stadium. It is the same connection, the same intention—there are just more people plugged into it.

[RELATED: ‘Patron Saint of Springsteen Fans’ Connects Grateful Recipients With Concert Tickets]

You shared a really deep and sacred bond with your uncle Clarence. He gave you your first saxophone, and now you play his instruments and use his mouthpieces when you perform with the E Street Band. You once explained, in a podcast interview with Rolling Stone, that Clarence gave you “direction in terms of letting your soul speak”—to “cut your gut open and see what comes out.” Would you say that guidance has been more freeing, because it has less to do with technique? Or more intimidating, because it requires a lot of intense vulnerability? Or both?

Yeah—you know, I think that Clarence and I kind of spoke the same language in a lot of ways. We were really similar in a spiritual sense. So a lot of it, I think, was observation, and also direction. He would give me really subtle things to help me on my journey—but almost, like, [in] riddles. Like a sage. [Laughs.]

But those kinds of things—they continue to be helpful, and they change over time. Whereas just a direct technique in terms of playing wouldn’t be the same, I suppose.

That being said, I certainly listened to him play. I understood how to play my horn because of how he played his horn. So the technical lessons were from listening, and watching him breathe, and leaning into that expression that he was giving.

Do you have a favorite E Street saxophone solo to play, or maybe one that you’re finding especially poignant or fun on this current tour? Or one that you think will stand out as emblematic of this tour?

Interesting. I don’t have a favorite saxophone solo—my feelings about that haven’t changed over time. It’s all scripture for me, you know? There is a beautiful weight in each one of those moments. But if there’s a bridge between the E Street story and my story, it would probably be “The Promised Land.”

You once told the New York Post: “Even when I’m onstage, I’m still watching the show, wondering where it’ll go. I still know when there’s something supernatural going on.” You had a very religious upbringing, and there was a limited range of music allowed in your house. Your dad was a band director for the Marine Corps, so you heard a lot of John Philip Sousa and marching-band music. You didn’t even take to rock ‘n’ roll immediately when you were first exposed to it. Looking back, do you think your religious upbringing opened you up to that attunement to the supernatural that you experience now? Or do you think there’s just a heightened sensitivity to it in your blood?

Absolutely—I think both of those are true. My father was Southern Baptist; my mother was Catholic. When I was born, I was Catholic, and then we switched over, shortly after, to my dad’s church. Growing up, I started playing music in the church. That’s where I started to perform. And I absolutely would agree that I had an awareness of that language of the soul at an early age from that.

That being said, I do think that [music] is sincerely the language of the soul and transcends religion, you know? So I hope that I would have found my way to this communicative process inevitably. But I hope that I am more aware of it because of my upbringing.

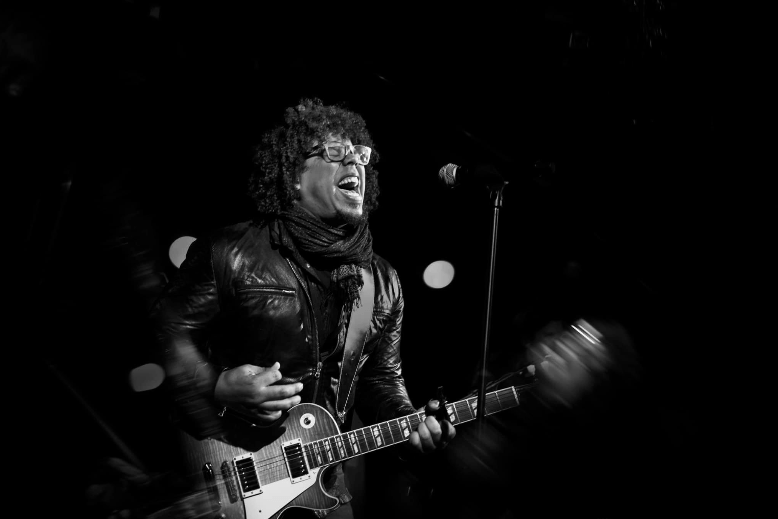

Photo: Courtesy of Tara Keane Photography

Outside of the E Street Band, you also play the piano, drums and guitar. What’s your composing process like?

It’s all over the place. [Laughs.] Sometimes it’s super spontaneous. I mean, sometimes it’s a dream. Sometimes I wake up from my sleep, and I was in a dream, listening to a song. Sometimes I’m walking down the street and I just hear it—it just comes into my head. And other times, I’m just venting on an instrument, and out of that, I hear something and I think, Oh, I should hold onto that.

The process of completion looks totally different for each of those. When I have a dream, for example, I’m just trying to remember it and put all the pieces back in. If I’m just walking down the street and something downloads into my brain, I just have to learn it. But if I’m venting, and just getting stuff out from my soul on the piano or guitar or saxophone, then there’s a lot more effort involved—oftentimes it’s just music in that situation, not lyrics. And then I’ll have to later sit down and write some thoughts and feelings down, and then find a way to pair that to some of these melodies or instrumental pieces that I had expressed.

I sort of prefer when it just comes to me. [Laughs.] But that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s going to be the most significant. It comes in all forms. But I guess it feels more powerful when it just happens.

Do you have any specific or eccentric pre-performance rituals?

I like to be quiet and alone and meditative. I just spend a little bit of time in prayer and meditation—and breathing—and really focus on being as present as possible. And feeling a connection with the ground that I’m standing on, and with every person that’s in the room before I walk on that stage.

And the first thing I do when I get on the stage is: I look to see where the farthest person is in the room, so that I can be aware of where I’m projecting to—where I’m gonna try to extend myself to. ’Cause I want that whole space to feel like a hug.

This interview has been edited and condensed for brevity and clarity.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.