Charles Rosen has done a lot in his 56 years. The Ontario native has been a lawyer, an indie film producer, an ad man, a political consultant, a criminal-justice reformer, a TED Talk futurologist, a Manhattan bachelor, and a Montclair dad. Add to this kaleidoscopic résumé Rosen’s current incarnation as a farmer and cidermaker—one who believes that his 108-acre Ironbound Farm and Ciderhouse is a working model of a better world.

“Ironbound is a scrupulously organic, self-sufficient, biodiverse ecosystem that demonstrates how the world can heal itself,” Rosen says, “and recapture the joy of nature. For me, coming to the farm every day is exhilarating.”

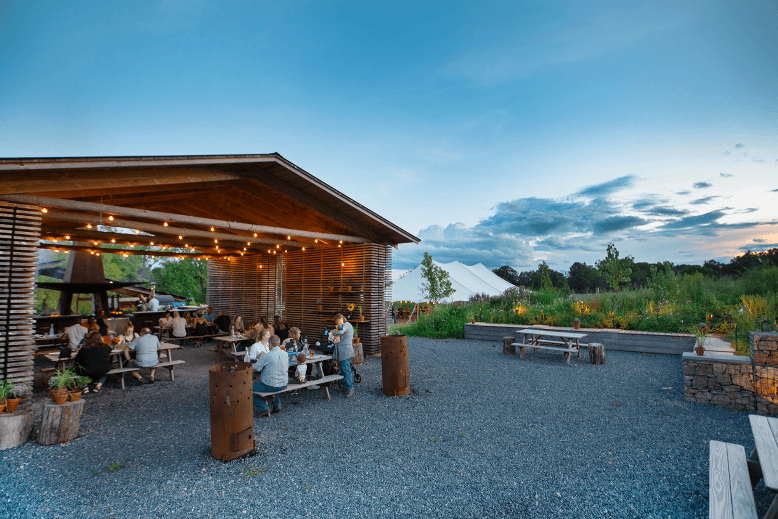

A Hunterdon County destination, Ironbound offers thirsty and hungry visitors rustic Jersey pleasures galore: a scenic hard-cider tasting room and bar; cider and food pairings; an organic eatery with a full menu of seasonal, local dishes; special chef’s dinners and other events; a well-stocked farm market; scenery, trails and self-tours; live music; good coffee and Wi-Fi; and plenty of food for thought.

NJM: The Garden State is rich in organic farms. What makes Ironbound different?

Charles Rosen: Where do I start? We do it all. We’re a full-fledged farm raising livestock like cows, sheep, goats, pigs and chickens. We’re an apple orchard for the ciders we make. …Alongside thousands of apple trees, we grow vegetables like squash, lettuces, parsnips, pumpkins, beets and potatoes. We cultivate herbs and mushrooms, and we grow fruit such as cherries, peaches, Asian pears and gooseberries. Our farm market sells produce, meats, eggs, honey and much more, along with other Jersey farms’ products like artisanal cheese.

A full menu with seasonal, local dishes is cooked on an open flame. Photo courtesy of the Ciderhouse at Ironbound Farm

What’s truly unique about Ironbound Farm?

Ironbound is beyond organic. It’s a remarkably sustainable farm, from the soil up. Our team calls it “regenerative.” The land, the crops, the orchards, the animals, the humans: Ironbound is a symbiotic community where everyone does their part. The microbes in the soil make things grow. The pigs do the rooting. The chickens fertilize the crops and eat the insect pests. The bigger animals eat the weeds. And the people who work here are sustained by our cider income.

On the web you’re described as a “visionary.” What’s visionary about a farm ecosystem?

This is a true community, meaning it takes care of everyone. Ironbound’s profit is not siphoned off by a wealthy owner with three homes while employees scrape together their monthly rent. I wanted to prove that a for-profit business could be a force for social good within our economic framework. Ironbound Farm opened in Newark in 2011, and 85 percent of its workforce was returning to society after serving time.

[RELATED: The 30 Best Restaurants in NJ]

How has Ironbound changed?

Our concept, facilities, growing practices and community commitment have continually evolved. By and large, our regenerative framework is working. Ironbound’s profits go back into the farm and its workers. And the farm enriches the larger community, such as other local farmers who grow for us what we couldn’t get to that season.

How can this model work for other industries or systems?

Ironbound is a microcosm of how a system can create a better life for everyone. Everything and everybody contributes and everyone benefits. This model could apply to all of agriculture and industry, to healthcare, education, politics, the economy, transportation, sports—you name it. Every living thing would become a partner in making things succeed.

Although Ironbound Farm is not located in Newark, it has its roots there and remains inspired by the city, once the country’s cidermaking capital. Photo courtesy of the Ciderhouse at Ironbound Farm

This sounds very utopian.

We need to heal this planet, and the Ironbound model really could work. I know this because we’re doing it. I come to the farm every day at breakfast time and watch our employees—farmhands, animal caretakers, cidermakers, cooks—hang out together, laughing and pitching in, when they seem to have nothing in common. But they do. Their common goal is the farm, which is their daytime home, a place of achievement and pride.

Why does your farm, near New Jersey’s western border, have the name of a Newark neighborhood?

In one of my earlier endeavors, I worked in Newark as a consultant to Mayor Cory Booker. I’m a lawyer and I have a strong sense of social justice. I got very interested and involved in how things work, or don’t, in Newark. Along the way, I learned that Newark was once the country’s cidermaking capital, centered in the Ironbound District. And that America’s earliest version of Champagne was carbonated Newark cider. This heritage is just breathtaking to me.

What made you want to produce cider yourself?

I was inspired by the thrilling true story behind the revival of New Jersey cidermaking. Here’s what happened. In the 1600s and 1700s, Jersey cider was sold throughout the Colonies—first Dutch, then English, and later the 13 states. Cider preceded America’s beer industry by centuries.

And cider served a purpose. Early on, there was no public drinking water. Apples were ubiquitous, so people drank cider instead. And Jersey cider was largely made from one intensely flavored yellow apple variety, the Harrison. It grew in profusion in the Newark water basin, today’s Essex County.

This is getting suspenseful.

Well, Newark’s cider industry was killed off. But it wasn’t done in by the anti-alcohol temperance movement of the 1800s, which culminated in Prohibition a century ago. Hard cider was produced and sold during those repressive decades because it was still thought of as a beverage and not as booze.

What happened to cider was big business. When Prohibition ended, mass-market beer breweries cropped up, and liquor importers flooded the American market with European spirits like vodka and gin. Cider came to be regarded as rural and déclassé; we’re talking generations before today’s artisanal craft movement. Newark cidermaking basically shut down. The Harrison apple was no longer cultivated, and the people who thought about it figured it had become extinct.

So how was the Harrison revived?

In 1976, impassioned botanical hunters—sort of plant detectives—became convinced that forgotten doesn’t mean gone, and they spent years tracking down the Harrison apple. Eventually, they discovered a lone tree in Livingston, fittingly at the site of an old cider mill. This tree became the progenitor of all the Harrison apple trees in New Jersey today, including those at Ironbound.

Wood-fired pizza is a must-try. Photo courtesy of the Ciderhouse at Ironbound Farm

Did you maintain the tradition of Newark cidermaking?

Our original business, New Ark Farms, started up in 2011 in, yes, Newark. But state law required us to have a minimum of three acres of fruit growing at our site of cider production. That’s why we moved our Ciderhouse an hour west to our Asbury fields.

How did you go from one Harrison apple tree to the thousands at Ironbound?

With twists and turns. It took years, a lot of botanical brilliance, and good luck to counter the bad. Our first cider batch was bottled in 2016, but with mature apples from our local partner growers. At Ironbound, we now care for 10,000 healthy and happy Harrison trees. We grow other apple varieties too and continue to source some of them from needy nearby farms. What I pay these farmers goes right back into the community.

Do you use exclusively Jersey apples in your ciders?

They’re made mainly with heritage apples native to New Jersey, but a few of the apple varieties are now grown in Pennsylvania or New York. Some ciders are single varietals and some are a blend. But every one of our ciders is 100 percent apple, whether a sweet or bittersweet variety. No fillers, no additives, no sugar, no gluten. The apples’ fermentation creates the alcohol content, which is 4.5 to 8.5 percent, like beer. Our four fortified Ironbound Imperial Ciders are 18 percent alcohol. That’s 36 proof and packs a punch.

I’m hoping you produce a cider called Harrison.

We’re spotlighting New Jersey heritage apples in a trio of ciders we introduced in 2022. One of them, with the name Harrison, is made solely with that apple. The other two heritage ciders are Jersey apple blends.

I understand that your cidermaker, Cameron Stark, was a longtime winemaker. How do Ironbound ciders compare to wine?

We brought in a renowned Napa winemaker because ciders can be as well-composed as wine. Both cider and wine need to balance the fruit’s acids, tannins and natural sugar. Cameron’s winemaking expertise allows us to create ciders as harmonious, palate-pleasing and complex as wine.

Our cider has turned out to be incredibly versatile. We’ve experimented successfully with infusing our cider with tasty things like ginger or hops—the tart flower in beer—or with Jersey fruit like gooseberry, cranberry or aronia berry.

The entire Ironbound team gets into tasting and appraising our own cider. And so do visitors to our Tasting Room and Ciderhouse eatery. Some of our ciders are available only through Ironbound, and some are sold in stores and markets.

“Nature has provided us a roadmap of how to live and thrive. If we follow it, we can rebuild our broken world,” says Ironbound Farm’s Charles Rosen, seen here harvesting. Photo courtesy of the Ciderhouse at Ironbound Farm

What can cocktail drinkers order at Ironbound?

They don’t feel left out. Our beverage director and mixologist, Danielle Nguyen, designs delicious cider-based cocktails with fruity, herbal, spicy, fruity or floral touches. They’re as multifaceted and exciting as spirits-based drinks.

Do you serve food and cider pairings?

Yes, and they’re a treat. The Tasting Room’s pairings match our ciders to seasonal, local food cooked on an open flame. Everything we serve—farm vegetables, foraged mushrooms, meat, game, poultry, fish—grows or swims in the Garden State.

Why are craft ciders on the rise?

Hard cider is being revived, both by the megabrands and artisan cidermakers. But I sense that people don’t want to see the quirky, small-batch cider label they’ve discovered get co-opted by big brands the way craft beers have been. I’m constantly reading or hearing about a beloved local beer being vacuumed up by an industrial brewery that can advertise in the Super Bowl.

But quite a few people are intent on preserving and supporting handcrafted traditions like local cider. Distinctive small businesses are an expression of American ingenuity, and they make daily life interesting. Not to mention, fresh, pure hard cider tastes so good. And it’s gluten-free besides.

What would need to happen for our entire civilization to function like a certain harmonious, community-serving, regenerative farm that makes great cider?

Ironbound is the opposite of the way our society is constructed. Today’s agribusinesses deplete and poison the land in pursuit of profits. The crops are genetically altered and treated with toxic chemicals. Why should corporations own our food and make us sick? Why should farm workers, often prisoners and migrants, be treated like feudal serfs while industrial-farm CEOs are billionaires?

Ironbound believes that food must be natural and good for you. And that an individual’s success must come from, and benefit, the entire community. Agribusinesses and other mega-corporations are crushing the American dream of locally-anchored businesses and healthy, affordable lives.

Your philosophy is simultaneously retrogressive and radical.

Nature has provided us a roadmap of how to live and thrive. If we follow it, we can rebuild our broken world. And if you work in a community-based system like Ironbound Farm, you already know this can be done. I am optimistic for our future.

Ironbound Farm and Ciderhouse: 360 County Road 579, Asbury, 908-940-4115; reservations by phone or Resy strongly recommended.

No one knows New Jersey like we do. Sign up for one of our free newsletters here. Want a print magazine mailed to you? Purchase an issue from our online store.