On a bright Saturday morning on the last weekend in May, Joseph Wysocki, chief of the Camden County Police Department, approached more than 200 protesters gathered outside a hair salon owned by a young woman named Yolanda Deaver. It was the starting point for a march that would make its way down Haddon Avenue to the front of police headquarters on Federal Street. This was one of many such demonstrations that took place in cities across the United States on May 30 as protesters called for justice following the death of George Floyd while in the custody of the Minneapolis police.

Camden’s rally would prove to be unique in some unexpected ways. It started when Wysocki greeted Deaver outside her salon and asked if he could march alongside her.

“From the moment I knew Yolanda was organizing the march, I knew I wanted to be a part of it,” says Wysocki, a 30-year Camden police veteran who had taken over as chief just nine months earlier, following the retirement of Scott Thompson. [Update: Wysocki announced his own retirement from the force after publication of this story.]

Joseph Wysocki, chief of the Camden County police, greets Yolanda Deaver outside her hair salon on Mt. Ephraim Avenue. Wysocki joined Deaver and hundreds of others in a May 30 march for social justice. Photo by Branden Eastwood

“What happened with George Floyd’s death was horrific,” says Wysocki. “I wanted our people to know that I was with them and just as outraged as they were. And I wanted them to know our department was with them, too.”

In stark contrast with the chaos and violence that erupted in other cities that day—including across the Delaware River in neighboring Philadelphia—Camden’s march was without incident. More than 30 Camden police officers marched in solidarity with the peaceful protesters, joining as the crowd chanted, “No justice, no peace, no racist police.”

Typifying the day, Wysocki was photographed helping to hold the lead banner, which read “Stand in solidarity,” while raising a fist in support of the theme: Black lives matter. The photo went viral, and within a week, the Camden County Police Department (CCPD) was the subject of headlines in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the BBC and elsewhere.

To be sure, a good deal of the coverage focused on the peaceful nature of the march—hardly a given in a city that experienced devastating riots sparked by police brutality in 1969 and 1971. But an equal amount of bandwidth was given to the notion that Camden’s relatively new policing structure could serve as a model for activists and civic leaders calling for criminal-justice reform in other American cities.

To understand the changes in Camden, one has to look back to May 2013, when Camden dissolved its 141-year-old city police force and replaced it with a new, county-run metro department. The concept—spearheaded by the Camden County Board of Freeholders, led by director Louis Cappelli Jr.—was to make the department financially leaner and more technologically savvy, while also revamping its culture.

To that end, the CCPD has spent the past seven years emphasizing what its leaders call “community policing.” The model requires cops to walk dozens of beats throughout the city, regularly canvassing neighborhoods on foot and keeping an eye out for trouble. At the same time, they can get to know local residents and business owners. The CCPD—with an annual budget of about $70 million—also holds community events, including neighborhood barbecues, ice cream parties and pickup basketball games, where officers shoot hoops with local residents. In keeping with the spirit of this new policing ethos, when the May 30 rally was over, officers hosted a neighborhood cookout with hot dogs, hamburgers and ice cream.

It was an irresistible narrative for media outlets to explore during a summer of civil unrest and tension. In an article titled, “Disband the police? Camden already did that,” the Los Angeles Times reported that Camden’s restructuring of the force “marked a turning point for the city,” and that “its revamped police force is cited as a potential model for Minneapolis…and scores of other communities seeking to reform police practices.”

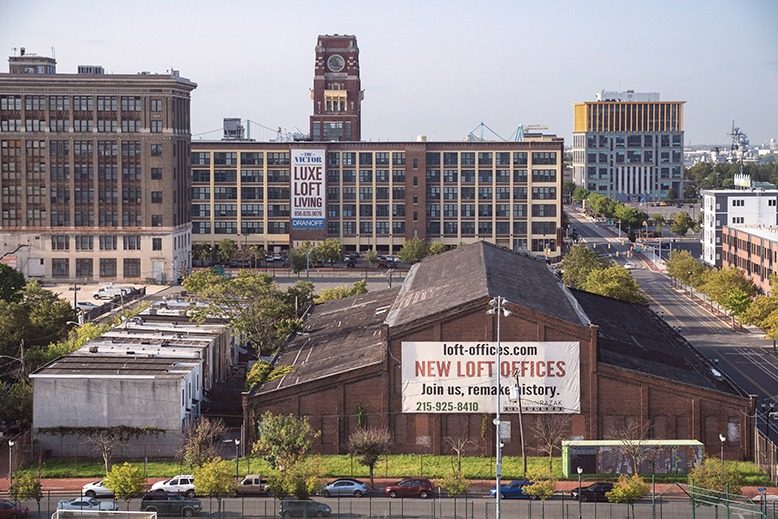

But on closer examination, a more nuanced picture begins to emerge. The story of the CCPD is part of a larger and more complex narrative involving a decade’s worth of revitalization efforts in Camden. It includes massive downtown and waterfront development projects, with new office buildings and market-rate housing changing Camden’s profile. Add the ever-expanding footprint of legacy institutions like Rutgers University and Cooper University Hospital, an infusion of more than $450 million in public and private funding for rehabbing old schools and building new ones, and the arrival of large corporate entities, most prominently Subaru, Holtec International and the Philadelphia 76ers.

The Philadelphia 76ers opted for Camden. Photo by Branden Eastwood

Such major initiatives are rarely without controversy. Certainly, they shifted the public perception of a place that had recently been known as the most dangerous city in America. But some residents, community organizers and activists say the investments in Camden have not resulted in demonstrably better lives for Camden’s citizenry. These critics contend that many of the recent advances have come about by taking power out of the hands of Camden residents.

“I always say that truths don’t always have to be competing, and multiple truths can exist in the same space,” says Keith Benson, a longtime political activist and head of the Camden Education Association. “It’s true that Camden has needs to address and changes to make. But the mechanism to facilitate those changes—by shifting power away from the local public and giving it to the county and state—has been nondemocratic and has marginalized residents. That is also true.”

To Benson’s point, the Camden City School District superintendent has been a state-appointed position since then Governor Chris Christie announced a state takeover of the district in 2013. The new police force is a county-controlled entity. And many of the headline-grabbing development projects have come by way of enormous state-sponsored deals into which the average resident had no input, while wealthy and influential individuals—most notably, insurance executive and Cooper University Health System chairman George Norcross III—wield extraordinary authority and, critics say, are positioned for personal gain.

[RELATED: A Conversation with George Norcross]

While big-ticket development is touted under a Camden Rising public relations theme, small businesses and neighborhood nonprofits say they toil in relative obscurity, prompting many to wonder: Is Camden actually rising, and, if so, for whom?

“I think the Camden Rising narrative is toxic, because it doesn’t account for the vast array of inequities still being experienced in this city,” says Rutgers-Camden public policy professor and blogger Stephen Danley. “And it contributes to one of two conventional media narratives about Camden: either everything is terrible, or everything is getting better. The reality is much more complicated.”

Open space along the river. Photo by Branden Eastwood

As almost every metric demonstrates, Camden is safer today than it was before the police department was restructured seven years ago. Since 2014, violent crime in the city has dropped by 33 percent, with a 19 percent decline in aggravated assaults, a 60 percent drop in robberies, and a 72 percent decrease in murders and manslaughter. As of late July, there had been a total of just eight homicides in 2020. In 2012, there were 37.

“I think what you see is the community working with us. We’re not strangers anymore,” says Wysocki, adding that excessive-force complaints have dropped from 65 in 2014 to just three in 2019. “What that does is allow us to build bridges with residents of the city so crime doesn’t occur in the first place.”

Freeholder director Cappelli is equally enthusiastic. Yet he warns that it won’t be easy to replicate Camden’s success elsewhere.

“It’s not the model, but rather the philosophy behind the model,” says Cappelli. “Each resident needs to be treated with respect…If you start with that philosophy in mind, I think some incarnation of our model can work everywhere.”

Dan Norton of the King James Bible Baptist Church preaches in a vacant lot. Photo by Branden Eastwood

Despite the encouraging metrics, the metro force is not without its critics. In the wake of the windfall of national kudos for the CCPD in June, activists and political writers took to the Internet to argue that, while crime statistics may have trended in a positive direction, the CCPD is by no means a radical reimagining of American policing. Additionally, some local leaders remain angry over the way they say the county department was foisted upon them.

“When all those headlines started cropping up, we said, ‘Okay, if we can’t control the narrative, we have to at least present a counternarrative,’” says Richelle Lee, communications, press, publicity and youth work chair for Camden’s local NAACP branch. “People weren’t getting the whole story.”

Lee recalls 2013, when a coalition of Camden residents petitioned for a ballot initiative aimed at halting the dissolution of the city force. In response, then Mayor Dana Redd successfully sued to stop the ballot initiative. The frustration then, like now, was that the department would fall under the auspices of Camden County and not the city, leaving residents without a voice in its operations or future makeup.

“They love to talk about broad things like community policing, but that went out the window when the people stopped being the priority…they forgot about the people. They are public servants, they work for us. So for the mayor to contribute to that oppression, that’s what did it. It was a first step toward what we see today,” says Lee. “And while the free ice cream and barbecues are great, this isn’t community policing. Community policing is when you live in the community and you reflect the community.”

Here, Lee articulates another concern some have about the CCPD—namely, that it’s too white and doesn’t count enough Camden residents among its ranks. The numbers bear this out. According to Wysocki, 48.5 percent of CCPD officers are minorities. Specifically, 25.8 percent of the force is Latino; 19 percent is Black.

It’s a concern for the chief, who says one of his top priorities is making sure the department “better reflects the diversity of the city.” But it remains challenging, he says, because of the state’s Civil Service Commission, which requires all municipal police applicants to complete an Entry Level Law Enforcement Exam. Wysocki says the test is “racially biased.”

“I could have a 21-year-old man from North Camden who wants to be an officer and meets every requirement—except he’s unable to pass the Civil Service exam,” says Wysocki. He recently sifted through 500 applicants provided by Civil Service and found only 53 came from Camden. “I should be able to hire from just Camden, because the residents are the ones who really understand the challenges of the city. I’m not knocking officers who come from other places, but culturally speaking, there’s no learning curve when you hire residents. And I think it raises the trust factor as well.”

Dilapidated homes like these near Front and York streets symbolize Camden’s continuing needs. Photo by Branden Eastwood

As far as the pop-up barbecues, free ice cream and basketball games are concerned, some say they merely deflect attention from the city’s stubborn, institutionalized problems, including poverty, drug addiction and abandoned infrastructure.

“All of that community stuff is elementary. There’s nothing advanced or progressive about barbecues and free ice cream,” says Roy Jones, a Camden resident and longtime political activist. “Do you think a drug dealer is going to stop selling drugs because you’re handing out hot dogs? It might make a few people feel more comfortable, but they’re still missing an empowerment plan to reduce crime. And that means recognizing that people are engaging in crime to make ends meet.”

A parking lot in Bergen Square, the city’s “most desolate” neighborhood. Photo by Branden Eastwood

Driving around the city on a recent July afternoon, Camden resident and community organizer Sean Brown stops at the corner of Kaighn Avenue and 7th Street. This is part of the Bergen Square district, which Brown calls “the most desolate and uncared-for neighborhood in the city.” The scene outside the car testifies to his assessment.

A riot of weeds hides the trash, broken glass and drug paraphernalia in a sprawling, overgrown vacant lot. Until about two weeks earlier, the lot had been home to a tent city for dozens of homeless individuals. The city cleared the encampment, but gaunt and desperate-looking individuals still wander the adjacent sidewalks. They are most likely addicts, Brown says.

“This is where we need economic development,” Brown says, gesturing to the vacant lot. “But this scene doesn’t call upon people to invest. It calls upon people to get out.”

Community organizer Sean Brown. Photo by Branden Eastwood

Continuing the drive, we encounter similar landscapes. Overgrown lots strewn with discarded tires and trash. Boarded up buildings. Homes with fortress-like bars that cage entire ground floors. And individuals who shuffle through the hot, summer streets, looking like they might plunge to the ground at any moment.

“They’ve got that dope lean going on,” says Brown, a father of two who owns DuBois Douglas Strategies, an agency that provides strategic planning, project management and grant-writing services to local businesses and nonprofits. “Only by the power of god are these people held up.”

Friends found David Zane, 32, a drug addict, living under a bridge in Bergen Square. Photo by Branden Eastwood

In Brown’s assessment, scenes like these don’t suggest a policing problem. In fact, in characterizing the CCPD, Brown says, “I don’t know of any police department that is as self-aware and introspective as the metro police. They want to get this right.” Rather, these streets indicate the socioeconomic challenges that still plague many parts of Camden to various degrees. (As Brown drives through East Camden later that day, we pass charming, tree-lined blocks lined with single-family homes and manicured yards.)

In recent years, employment statistics have provided new hope. While the pre-Covid-19 poverty rate hovered around a dispiriting 35 percent and the median household income remained stuck at about $27,000, Camden’s unemployment rate had fallen to 7.7 percent by March 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic boosted that figure to 20.8 percent by the end of the summer, but many are optimistic that a swift recovery will occur when the country returns to some degree of economic normalcy.

“Camden’s not just a story about how screwed up everything is,” says Brown. “There are pockets of amazing things and amazing people in this city. People who aren’t just waiting around for someone else to fix the problems. People who pursue their dreams. But these people aren’t getting a government or corporate system that cares back and shows them that, because they’ve invested in the city, the city will invest in them.”

The American Water building and the new Triad 1828 Centre as seen from Philadelphia. Photo by Branden Eastwood

The claim that Camden undervalues its most engaged citizens is a common theme—even as fresh capital pours into the city. In the last decade, large-scale developments have accounted for more than $2.5 billion of investment. The Philadelphia 76ers spent $82 million on a 120,000-square-foot practice facility and office building located on Front Street. Subaru of America doled out $118 million to bring its 250,000-square-foot corporate headquarters from Cherry Hill to Camden. Other corporations that have put down roots in the city over the past few years include energy-tech giant Holtec International, global shipping and logistics firm NFI, and American Water, the nation’s largest publicly traded water utility.

Still, many of the city’s prominent organizers and activists express cynicism and frustration about Camden’s most high-profile development projects, which they contend haven’t benefited residents on the ground. What’s more, there’s lingering resentment—and statewide controversy—concerning the tax breaks that lured these companies to the city in the first place.

“There are companies you have to pay to be here because they don’t really want to be here, versus the people who do development from the inside out because they love this city,” says Rutgers professor Danley. “If it takes a $100 million tax subsidy and a six-story building cut off from the people, you don’t get to declare that Camden is rising and that you’re here to help the city. That’s what you do if you’re scared of engaging with the city. But on the flip side, you find local businesses and entrepreneurs who are rooting down in neighborhoods and hiring locals, which is a different type of investment.”

Neighborhood entrepreneur Adam Woods oversees workers at his shop, Camden Printworks. Photo by Branden Eastwood

Gazing out at the intersection of Broadway and Webster through the window of his Camden Printworks shop, Adam Woods says that if he didn’t know better, he’d have no idea any of the big corporations were even in Camden.

“It’s not like I’m seeing a bunch of Holtec or Subaru employees walking down the street getting lunch or visiting shops,” says Woods, who’s owned this Waterfront South shirt-printing business since 2006. The corporations, he says, “have a fortress mentality.”

An engaged and successful neighborhood entrepreneur, Woods has eight employees—some from Camden—and often partners with local schools to coordinate internships for young people. He contends the influx of corporate entities has “done nothing for public safety and nothing for the local economy,” despite the oft-told trickle-down storyline.

“There’s this theory that if I work at Subaru or Holtec, I’ll drop off my dry cleaning and get lunch and get my car fixed in Camden. But why would I do that? I live in Mount Laurel or Cherry Hill! That’s where I’m going to do that stuff,” says Woods. “And it’s that top-down narrative which helped them get those huge financial incentives to come here.”

A boarded-up building blights the streetscape across Broadway from Woods’s print shop. Photo by Branden Eastwood

One needs to again turn back to 2013, when then Governor Chris Christie signed the Economic Opportunity Act (EOA), which carved out billions of dollars in tax incentives designed to lure corporations and developers to some of New Jersey’s most beleaguered cities. Camden reaped the largest benefit, securing $1.6 billion in tax subsidies from the New Jersey Economic Development Authority (EDA) for companies that agreed to invest in the city. Camden also agreed to extend local tax abatements to cut those companies’ property taxes by about 70 percent over 20 years.

A 2019 investigation by public broadcaster WNYC and the nonprofit ProPublica found that at least $1.1 billion of the available $1.6 billion went to businesses closely associated with Norcross, widely considered the most powerful unelected individual in New Jersey and the most forceful private-sector proponent of the EOA. Beneficiaries of the tax incentives—the majority of which have not yet been doled out—included Norcross’s insurance brokerage, Conner Strong & Buckelew, and its partners, the Michaels Organization and NFI LP. Tax breaks were also awarded to entities for which Norcross is a trustee, such as Holtec, and clients of the law firm owned by his brother Phillip Norcross, including Subaru and the 76ers.

But in an exclusive interview, Norcross—who calls the WNYC/ProPublica piece “a misguided report littered with inaccuracies and innuendos”—tells New Jersey Monthly that the anger about the tax incentives is unwarranted.

“These companies, including my own, could have gone anywhere else,” says Norcross, who chairs the Camden-based Cooper University Health System and the local arm of the Texas-based MD Anderson Cancer Center. “They didn’t move here because of the tax credits. They moved here because they wanted to be part of the revitalization that was going on. But no doubt an incentive was needed, because who the hell is coming to America’s most dangerous and poorest city unless there was an opportunity to do something?” (Norcross’s insurance brokerage, as well as the Michaels Organization and NFI, relocated from Camden’s suburbs to a new, 18-story, waterfront tower called Triad 1828, which the partners built with EDA tax incentives.)

Cooper University Health System chairman George Norcross III gazes out at Camden’s revitalized waterfront from the 19th floor of his insurance company headquarters in the new Triad 1828 Centre. Photo by Branden Eastwood

What’s more, Norcross—a Democrat who was born in Camden and considers himself “Camden’s greatest cheerleader for more than 30 years”—maintains that, in addition to improved public safety and schooling, building a large corporate employer base committed to a long-term presence in the city is critical to solving problems that have been plaguing Camden for half a century.

“The idea behind the [EOA] was to have people invest money in bricks and mortar, because then you can’t just pick up and move out. You’re committed to being here,” says Norcross.

Still, some are not convinced. “When you live in a place like Camden long enough, it feels like business as usual,” says Carlos Morales, executive director of the Heart of Camden, a nonprofit focused on community development and affordable housing in the Waterfront South neighborhood. “These large corporations feel like independent silos, and residents can become tired and angry because they don’t see the benefit. And that’s because there hasn’t been a benefit to residents. None at all.”

Like Woods, Morales points to Holtec—which is located in Waterfront South—and the dispiriting exercise of watching employees arrive for work each day, only to disappear into their respective buildings before driving home at night, presumably to the suburbs. He also recognizes, however, that the process of building meaningful relationships is a long game and says he’s eager to be “a bridge that starts a conversation about how a large company like this can be a part of the community.

“Holtec has neighbors, and they need to figure out how to be responsible to those neighbors,” says Morales, who is working on a 10-year neighborhood-improvement plan that includes striving for a more robust relationship with the energy giant. “Look, if you’re going to be here for the next 25 years, you need to consider how you can help improve the neighborhood.”

Bridget Phifer’s Parkside community development corporation has rehabbed close to 100 homes. Photo by Branden Eastwood

The Heart of Camden is a nonprofit community development corporation, one of several that aggregate a dozen organizations throughout Camden. They focus on issues like affordable housing, financial education and empowerment, and long-term community planning. While large corporate developments and partnerships may serve as the face of Camden’s revitalization, the CDCs are considered by many to be the city’s most effective assets.

Through a combination of grants, donations and public assistance, Heart of Camden has been responsible for building or rehabilitating more than 250 single-family homes for low- and moderate-income families since its inception in 1984. Other projects include the South Camden Theater, the Camden FireWorks art gallery, the Camden Shipyard and Maritime Museum, and the Nick Virgilio Writers House. Throughout the pandemic, the organization has served about 250 families every Thursday with everything from baby formula to cleaning supplies and meal distribution.

“We work in the trenches to help deal with issues the city just doesn’t have the capacity or resources to deal with,” says Bridget Phifer, executive director of a CDC, the Parkside Business & Community in Partnership, which has rehabbed close to 100 homes and converted 149 former multifamily rental properties into senior housing. It recently secured low-income housing credits for a 32-unit mixed-use space adjacent to Virtua Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital on Haddon Avenue and acquired 10 new housing units in the neighborhood for either rehabilitation or new construction—to say nothing of the community initiatives aimed at improving all aspects of life in the Parkside neighborhood.

Phifer says the arrival of large corporations in Camden has not resulted in a positive trickle-down effect for residents, and that it’s a “huge issue, because the neighborhoods have never been a priority.” Nonetheless, she’s hopeful that nonprofits like hers can begin forging investment relationships moving forward.

“The greatest asset any city has are the people who live there, so I think there should be a greater priority in our neighborhoods,” says Phifer. “But we can’t do it without city government, without big corporations, without the county. We need all the players at the table to make sure neighborhoods survive in a real way.”

The Cooper Plaza Townhomes were developed with marketing support from Cooper’s Ferry Partnership, a local nonprofit. Photo by Branden Eastwood

One of those players is Cooper’s Ferry Partnership, the city’s largest and most visible CDC. The 36-year-old nonprofit started as a waterfront-development firm, but has since worked on projects in other Camden neighborhoods, helping with marketing strategy for large-scale developments like the new 11 Cooper waterfront apartments and the recently renovated Cooper Plaza Townhomes. The latter is a stretch of 64 affordable housing units on Haddon Avenue. The influence of Cooper’s Ferry—whose board includes high-profile individuals such as former mayor Redd, the chief operating officer of the 76ers, and the president and CEO of Subaru—cannot be overstated. But despite their high-profile status, CEO Kris Kolluri says the organization’s primary focus is always “residents first.”

“Listening, understanding and developing resident-driven solutions to resident-posed challenges is our highest priority,” says Kolluri, a former commissioner of the state transportation department. “Everything we do is guided first and foremost by how residents want to solve problems with solutions that work on the ground in their neighborhoods.”

Cooper’s Ferry has its hand in a long list of commercial and community development projects, making it, as Kolluri puts it, “the tip of the spear” when it comes to Camden’s revitalization. However, Kolluri adds high praise for the city’s other nonprofits. He is bullish about the Camden Rising narrative and has the metrics to support it. For instance, a recent survey conducted by Cooper’s Ferry found that at least 1,413 Camden residents work in facilities that received tax incentives. That’s an increase of 163 jobs since similar data was gathered in April 2019.

What’s more, Cooper’s Ferry recently partnered with five additional nonprofits—including the New Jersey NAACP and the Latin American Economic Development Association—to launch Camden Works, a website and job portal that provides casework support, job fairs, information sessions, soft-skills training and job placement. According to Kolluri, Camden Works and its partner entities have hired 537 residents since November 2019, including 223 during the height of the pandemic, from March through July.

Cooper’s Ferry is also part of a new Camden is Bright Not Blight initiative to clean up vacant properties in the city and install specially commissioned public art at these sites in an effort to combat illegal dumping.

Kolluri acknowledges that some Camden residents feel they are living in a tale of two cities, with one story dominated by flashy, corporate developments and the other mired in urban blight. But to his mind, the complexities of Camden’s issues are the cause of all that angst.

“The tale-of-two-cities criticism reflects some frustration that progress is too slow, to which we say, the challenges that have to be confronted developed over a period of 50-plus years,” says Kolluri. “I understand the fierce urgency of now, but to somehow discount the progress that’s been made in the last 10 years and say that it’s not enough, or that it isn’t objectively helping the city, is unwarranted.

“For me,” Kolluri continues, “ideology without pragmatism is dogma. It’s doesn’t mean you can’t have belief systems or be passionate about something. But solving complex problems requires ideology paired with pragmatic solutions, which is what I think you’re seeing in Camden.”