Ulysses Grant Dietz describing a beautiful antique is in itself a thing of beauty. There’s the tale of its history, or provenance, illustrated in some book he may or may not successfully locate that moment in his brimming office at the Newark Museum. Then there’s the story of its creator or owner. And, there’s background about the times that produced the work.

As the museum’s senior curator and curator of decorative arts, Dietz brings a practiced eye to making acquisitions. A dapper guy who dresses like a New England preppie—which he is—Dietz does not let an object’s superficial qualities obscure its significance or soul. Considering jewelry, for instance, he might discern that some aspect of a piece—its genesis, its place in a design movement—is being drowned out by stones that practically scream their magnificence.

That’s the problem with jewelry: “It’s precious,” he says. “So people don’t stop and look at it as art, which is one of my latest missions, to get people to really look at jewelry for its design, not for the rocks.”

Dietz’s office is profuse with leaning towers of paper, assorted worn furnishings, and nineteenth-century artifacts. Posters of his exhibitions cover the walls. A visitor peels a stray business card from the bottom of her shoe. The 54-year-old curator is wearing one of his signature bow ties and owlish glasses. Usually in relentless good humor, he sometimes blurts out, “Gosh!,” even though it’s easy to imagine him tossing off bon mots with his colleagues; during our conversation, he makes casual references to “stuff,” “a biggie,” and “stupid things.”

Dietz oversees the 100-year-old museum’s American and European household objects, a collection that ranges from a 1770s teacup to an Arts and Crafts-style window from a Minnesota bank. Widely known for his expertise, he gets calls and e-mails from curators, dealers, and everyday treasure hunters seeking input in the realms of furniture, jewelry, ceramics, and silver—even clothing and quilts, since the museum has no curator of costumes and textiles.

A sharp appraiser who is also a sentimental softie, Dietz turns to a Beatrix Potter calendar from July 1980 to jog memories of his earliest experiences on the job. “On my very first day as a curator, a man came to see me about Jelliff furniture,” he recalls. John Jelliff & Co. of Newark was the state’s best-known maker of Renaissance Revival furniture during the nineteenth century. “Two weeks into my career,” he continues, “I went to Plainfield, and we were given an incredible quilt, which is probably the greatest one of its kind in the United States.” The medallion-pattern quilt, created from silks by Mrs. C.S. Conover in 1855, was in pristine condition; these days it comes out only for special exhibitions.

One of his first duties back then was getting rid of “things we had no business taking in” and politely turning away well-meaning benefactors bearing gifts. Yet, today the museum’s storage and exhibition spaces are still packed. “People think of us as a little museum, when in fact we’re a big museum stuck in a little box,” Dietz says. Excluding the science collections, the museum owns 110,906 items, of which 106,106 are in storage. “A museum’s job is to protect objects first,” he explains. “It takes objects out of the world and keeps them safe.”

This drive to preserve extends to his rich family heritage. Dietz, who grew up in Syracuse, New York, is a great-great-grandson of President Ulysses S. Grant. Living up to that pedigree has meant campaigning for the upkeep of Grant’s Tomb in New York and preserving ancestral anecdotes, like the one about his maternal grandmother, Edith Root—daughter of Elihu Root, secretary of state under President Theodore Roosevelt—who risked scandal by smoking cigarettes at Mardi Gras with Teddy’s daughter, Alice. Or how Grant, strapped for cash, had to borrow heavily from W.H. Vanderbilt.

The Dietz family business, from the mid-1800s until the 1990s, was lighting: whale-oil lamps, kerosene lanterns, then automotive lights and reflectors on Winnebagos. Not a hint of romance to this trade, Dietz thought, until he discovered an R.E. Dietz Co. catalog from the 1860s. It later inspired his master’s thesis on decorative lighting of the mid-nineteenth century.

A prep school education was expected, and he enrolled at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. At 15, he asked his father to take him on a two-week driving tour of Great Britain’s country houses. As an adolescent, he avidly clipped magazine photos of grand residences, studied their floor plans, and drew schematics of his own. Initially, he was more interested in a house’s bones than its contents, but his carefully mapped vacation engendered his future career. For two summers, while Dietz attended Yale, he volunteered to catalog the collection at the 1808 Lorenzo mansion, a historic site that he could see from his family’s cabin on Cazenovia Lake near Syracuse.

The teenager thought he might become an architect, but “that was, like, not going to happen—I can hardly add.” After Yale, his love for posh interiors propelled him to the Winterthur program at the University of Delaware, where he earned a graduate degree in early American culture, then proceeded directly to his one-stop career at the Newark Museum.

Dietz’s domain at the museum includes the hushed and stately Ballantine House, the 1885 residence of the wealthy Newark brewery family, which is attached to the northeast corner of the museum. In 1994, his exhibit “House & Home” reinterpreted the manse by telling the story of domestic life from the Colonial era to the present through the display of decorative objects.

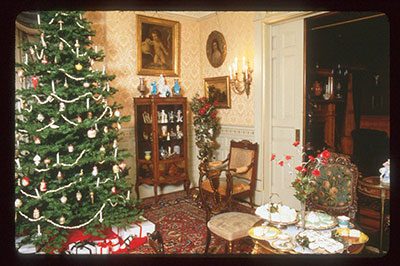

Every December, Dietz richly decorates the Ballantine House for the holidays—as they were celebrated in the 1890s. Greenery and garlands abound on the house’s warm, mahogany-paneled walls. (The Ballantine servants would have gone in search of Jersey-grown holly for decoration.) Dietz culls the museum’s array of fine silver and china for an open-house Christmas-eve tea, set in the parlor. Under the tree, lavished with antique ornaments and tin candleholders, sit a lovable bear or two and gift packages wrapped in papers of the period. Children hunt for little decorative birds hidden in the house.

Typically, the Christmas decor has included a dinner setting; this year, the dining room is occupied by Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare’s banquet-table-length installation, “Party Time: Re-imagine America”—a rakish depiction of a nineteenth-century dinner run amok, attended by eight headless dignitaries. (“We can hardly put elf hats on his figures,” Dietz deadpans.)

“This job drew me because there was this great house,” he says, “but there’s a whole collection in storage that I’ve been able to build on and expand and play with and exhibit—every year it’s something new.”

So what’s new? In a second-floor room, the curator recently opened the Lore Ross Jewelry Gallery, which includes pieces from the collection dated 1600 to the present.

“What drives us here is we want to tell a story, and we want objects to tell that story really well. That’s an old tactic that Mr. Dana used,” he explains, referring to John Cotton Dana, who founded the museum in 1909. “If you put a masterpiece there, and you surround it with objects that tell the rest of the story, then people come for the masterpiece, but they learn from everything else.”

Dietz’s current exhibit, “100 Masterpieces of Art Pottery: 1880-1930,” brings out many of the museum’s superb pieces, including Japanese-inspired Rookwood vases and one-of-a-kind works from the Royals (Worcester and Copenhagen). Other wares illustrate the development of styles or techniques. Dietz ventures that it’s the cultural importance, educational value, and diversity of these “modest objects” that sets Newark’s collection apart. A link to Newark’s manufacturing or artistic heritage makes a compelling reason for the museum to consider acquiring the piece. If only! He remembers paying a hefty sum for a fabulous walnut sideboard carved by Alexander Roux in the mid-nineteenth century, then beating himself up some months later when a silver-plated tea table made at the Tiffany & Co. factory in Newark for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair came on the market. Alas, he could not afford to purchase both.

“It really killed me because that was the ultimate Newark object,” he says, somewhat relieved that it ended up at the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute in Utica, New York.

Yvonne Markowitz, the Rita J. Kaplan and Susan B. Kaplan curator of jewelry at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (the only curatorship of its kind in the country), says little was known about Newark jewelry makers, particularly at the end of the nineteenth century, until Dietz mounted the 1997 exhibition, “The Glitter and the Gold: Fashioning America’s Jewelry.”

“The marketplace went crazy afterwards,” she says. “And now there are collectors who just collect Newark pieces. Even myself. I was pretty unaware of all the activity that took place in Newark, so Ulysses has really been opening new doors and making people inside and outside the United States understand that very important role of Newark.”

Amelia Peck, the Marica F. Vilcek curator of American decorative arts and manager of the Henry R. Luce Center for the Study of American Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, takes graduate students to the Newark Museum each year to hear Dietz lecture. “I think of Ulysses as an expert in American jewelry, pottery, nineteenth-century American culture, interpretation of historic houses, and the history of the White House,” says Peck. “He knows a great deal about every aspect of his collection.”

Dietz lives in Maplewood, which reminds him of his childhood environs. His ideal house is a mid-nineteenth century Italianate villa, but he and his longtime partner, software engineer Gary Berger, settled for a 1930s Tudor—decorated “in 1920s Grandma,” Dietz says. The living area is beautifully appointed with a passed-down parlor grand piano, R.E. Dietz fixtures, and family portraiture. (“Gary gets a little creeped out by all my dead relatives,” he admits.)

Despite the formality, it’s not a museum—it’s an active household where no one blinks when a drink splashes on the Oriental rug. The couple’s children—Grace, 14, and Alexander, who turns 15 in December—chatter as they sprawl on the furniture and feed biscuits to the dog.

Scanning a list of Dietz’s many writings—scholarly books and catalogs about furniture, jewelry, and art pottery—it’s hard not to notice the incongruous 2000 novel, Desmond: A Novel About Love and the Modern Vampire, in which one of the lead characters is an out-of-work curator. One of Dietz’s recent books, Dream House: The White House as an American Home, written with Sam Watters and published in September, serendipitously ties his ancestry to a house he has always loved.

Not surprisingly, his favorite presidential period begins with the Grants—he calls it the Mansion Era—when the White House “finally owns up to its potential” as a showcase rather than a cavernous, middle-class dwelling. “Ironically, Julia (Grant), who lived in a log cabin and grew up in a real vernacular house out in the West, looked around her and said, ‘So this is what people are doing now. I’m going to turn the White House into a house that’s worthy of its scale,’” Dietz says admiringly of his great-great-grandma. “And the White House finally becomes comfortable in its skin in terms of scale and richness.”

Back at the museum, Dietz ponders the dream acquisition that’s been most elusive to him. In fact, it may exist only in one of the museum’s paintings. In the background of an 1858 portrait of New Jersey Governor Marcus L. Ward’s children is a carved, Gothic armchair whose markings tie the Ward family to England’s Queen Anne. The museum was built on the site of the Ward house, and Dietz is mentally tortured that “some church in New Jersey has it sitting in a back room somewhere.”

“This is a chair any museum would kill for,” he says with a sigh. “It’s like the greatest Gothic Revival chair in America and it only exists in a painting….But at least we have the painting.”

Linda Fowler writes frequently about the arts for New Jersey Monthly.