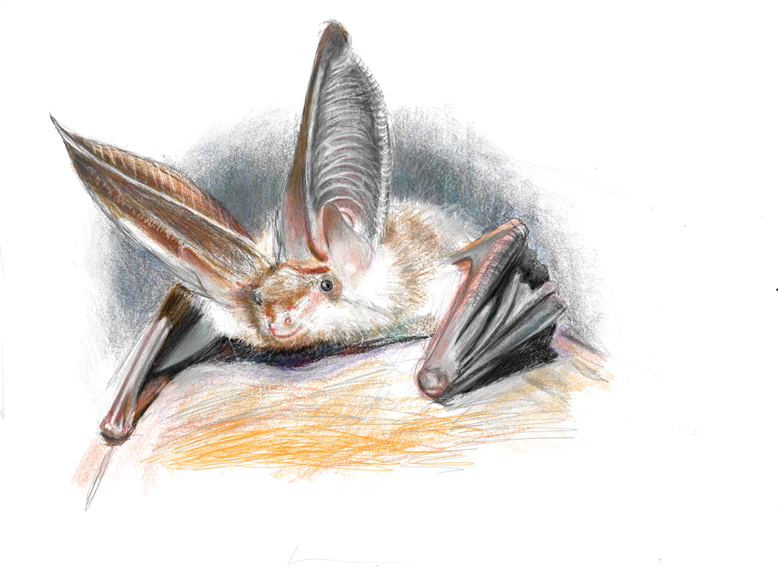

Northern long-eared bat. Illustration by Janice Belove.

The invasive fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans is believed to have entered the United States in 2006 after hitching a ride from Europe on the boot of an unsuspecting spelunker (cave explorer). The spelunker inadvertently deposited the fungus in a cave in Albany, New York, where it proliferated in the cold and damp den. While the hibernating bats slept, the fungus crept among them, leaving white markings around their muzzles and eating away at their wings—symptoms in bats affected by white-nose syndrome (WNS), a disease caused by the fungus.

“It attacks the wing membrane so they’ll actually have shredded wings,” says Stephanie Feigin, biologist with Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey. “It hurts, so it kind of wakes them up, and that costs them fat reserves and water stores that they worked all spring and summer to build up.”

Incapable of flight, the affected mammals sometimes fall to the floor of the cave, where they starve or freeze to death. If they can still fly, they may leave the cave to look for food. Outside, they are exposed to cold and struggle to find food to refuel their depleted and dehydrated bodies.

Since the initial outbreak, the fungus has radiated across the eastern United States, north to Canada and southwest to Mississippi, killing more than an estimated 6 million bats. The fungus arrived in New Jersey caves in 2009. Among the state’s affected species: the northern long-eared bat, which was listed as endangered last year. Once so abundant its population was not tracked here, it is estimated to have dropped in number by 99 percent.

Northern Long-eared bat. Photo courtesy of Blaine Rothauser.

The little brown bat, averaging 3 inches in length, has also been significantly affected. Their main hibernacula, located at Hibernia Mine in Morris County, saw a drop from approximately 25,000 bats in 2009 to 462 in 2015.

Biologists worldwide—including those in New Jersey—are studying bat species closely. Feigin says it’s unclear if affected species will be able to survive or how long it might take the bats to recover.

“We are seeing it level off a bit,” says Feigin. “We’re not seeing as many dead bats on the floors of hibernias.” However, she adds, “we’re not sure why we’re not seeing an uptick in the numbers, so that kind of raises a number of other questions.”

Bats are essential to the food chain in New Jersey. They feed on pests and pollinate vegetation. Because of their roles, they are estimated to be worth billions of dollars to the agricultural industry worldwide.

Feigin says humans need not fear bats. The mammals, she says, clean themselves more than an average house cat and rarely carry disease.

“Bats are secretive little creatures, and all they do is benefit humans,” she says. “Less than 1 percent of bats have rabies. You’re actually more likely to get hit in the head by a falling coconut than get a disease from a bat.”

Feigin says there are ways citizens can go to bat for the bats.

1. Do Not Disturb

Bats in New Jersey roost in abandoned mines, tunnels and caves, as well as in dead and dying trees and buildings. Disturbing bats can cause them to lose fat reserves, especially during hibernation, or could result in the spread of disease like WNS.

2. Hire A Professional

Bats sometimes find shelter in homes or commercial buildings. Killing or harming a bat is illegal, so evictions should be done by professional bat excluders who follow proper guidelines. A list of companies can be found at conservewildlifenj.org.

3. Install A Bat House

CWF offers free bat houses that can be installed on your property to attract a new or evicted colony. To build your own, contact CWF for blueprints and information.

4. Leave Dead Trees

These trees, known as snags, make great homes for various species including bats, who roost in them during spring and summer. If you have snags on your property, leave some standing as long as they do not pose a threat.

READ MORE: New Jersey’s endangered and threatened species are struggling to survive.