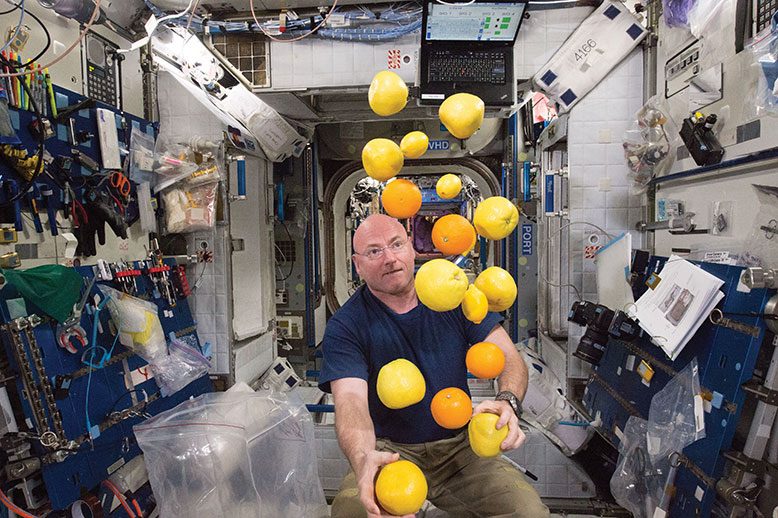

After nearly a year in space, New Jersey native Scott Kelly craved products from 249 miles below. In an e-mail to his then girlfriend, now fiancée, Amiko Kauderer, he expressed his longing for green Gatorade, strawberries, seedless grapes and several types of alcoholic beverages. Even bottled water would have been appreciated.

When he finally returned to his home in Houston in March 2016, he satisfied another craving, gleefully flopping sideways into his pool while fully clothed.

Kelly’s backyard plunge was a refreshing change from the International Space Station, where a cleansing shower involved using a moist towelette.

Not all of Kelly’s reentry experiences were pleasant. Once back on Earth, he developed painful rashes, a result of the limited contact clothing had with his skin while in space. He also had flu-like symptoms and swelling and discomfort in his legs.

“The worst thing,” Kelly tells New Jersey Monthly, “was having the blood fill your legs and feeling like you have these foreign tree stumps you’re walking around on.” Kauderer, a NASA public affairs staffer, describes Kelly’s feet as soft and floppy, like a water balloon. (They have since returned to normal.)

Kelly endured similar symptoms, although less severe, after travelling to the space station for six months in 2010. In all, Kelly, 53, has made four space flights, dating back to December 1999. His latest mission covered 143 million miles as he circled the Earth for 340 days—the longest stint in space for a U.S. astronaut.

During the mission, Kelly participated in several hundred experiments. To prepare future astronauts for a trip to Mars, scientists hope to learn from the physical changes he experienced. His condition will also be compared with that of his twin brother, fellow astronaut Mark Kelly. The two have provided blood samples, circulatory data and other information to scientists eager to understand the effects of space on the human body.

Scott Kelly’s bone formation, which typically reacts to the body’s needs, slowed during the second half of his trip. He also grew by 1 ½ inches as a result of the expansion of spinal discs normally constrained by gravity. Immediately after his mission ended, he returned to his pre-flight height.

Kelly also experienced unusual changes in his telomeres, small molecules in the body that are linked to aging. These, too, returned to normal after his return.

While scientists continue to examine the data on the twin astronauts, Kelly is sharing his story in a new memoir, Endurance: A Year in Space, A Lifetime of Discovery (Knopf), written with Margaret Lazarus Dean. In the book, Kelly, who was born in Orange and raised in West Orange, details his humble early years, including tensions with his father, a police officer who once used a wooden sculpture Kelly had made in school for target practice. His mother, 5-foot-4-inch Patricia Kelly, trained in the backyard for her police physical, eventually becoming the first female police officer in West Orange and one of the first female officers in the Garden State.

Kelly describes himself in his book as a “terrible student, always staring out windows or looking at the clock, waiting for class to be over.”

Unfocused and unmotivated academically, Kelly found his calling when, on a trip to the bookstore to buy snacks, he wound up buying The Right Stuff, Tom Wolfe’s account of America’s test pilots in the years leading up to the space program.

Kelly says the power of Wolfe’s writing electrified him, even if he had to look up the meaning of words like neophyte and virulent. Suddenly he had the outline of a life plan.

Wolfe spoke with Kelly by phone during his mission and met him for lunch several times after he returned. The author is thrilled that Kelly credits The Right Stuff with helping him discover his purpose in life. That, says Wolfe, is “the best compliment I’ve ever gotten.”

Kelly was also inspired in part by his brother. He recalls a conversation with Mark, who is older by six minutes. Scott was attending SUNY Maritime College at the time, and Mark was enrolled at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy. Scott invited him to a party during the Labor Day weekend. Mark declined—and urged his brother to do the same. They both had exams to prepare for.

While he resented his sibling’s lecture, Scott reluctantly followed his brother’s example—and aced his calculus test. “This is how people got good grades,” Kelly writes. “It was like a door had opened.”

Determined to repeat his academic success and follow through with his plan, Kelly became a fighter pilot and, ultimately, an astronaut.

In his book, Kelly shares anecdotes from his record-setting mission. Among the priceless moments: Kelly watched films and shows with his crewmates, including Fifty Shades of Grey in Russian.

At one point in the voyage, Kelly was running on a treadmill when he received a “red late-notice conjunction”— a warning that debris was heading toward the station, much like the debris that triggers calamity in the fictional film Gravity.

Kelly raced around the American section of the station, closing hatches. When he got to the Russian side, the cosmonauts hadn’t closed a single hatch. Instead, they offered to share an “appetizing appetizer,” as it said on the can. They knew there were only two possible scenarios: The debris would either obliterate the space station or miss it. (Eventually, Moscow mission control sent word that the debris had passed and the crew could return to work.)

Kelly conducted three space walks. Although the experience was awesome, it didn’t overwhelm or terrify him. He attributes that to his training and his ability to compartmentalize.

“If I were to take a moment to ponder what I’m doing,” he writes, “I should completely freak out.” Still, these were harrowing experiences. In the span of 45 minutes, the temperature shifted from plus 270 to minus 270 degrees. Glove heaters kept his fingers warm, but his cold toes distracted him. During the first spacewalk, Kelly spent 11 hours outside his orbiting home, which exhausted him mentally and physically. As he returned to the station, blood vessels burst in his eyes when he attempted to equalize the pressure in his ears.

Back on Earth, Kelly was initially “shocked” that Oprah Winfrey didn’t invite him to join her show. Then, he says, “I realized she didn’t have her show anymore.”

Kelly, who has officially retired as an astronaut, delivers frequent speeches and is pursuing several projects. Sony Pictures has the rights to turn his book into a movie.

He is in the second year of a two-year appointment as the United Nations Champion for Space. His mission is to promote space as a tool for sustainable development.

Living in the space station gave Kelly a unique sense of the vulnerability of Earth’s ecosystem. He says he would consider taking a role with an environmental group.

“Some parts of the world, especially in Asia, are so blanketed by air pollution that they appear sick, in need of treatment or at least a chance to heal,” Kelly writes. “The line of our atmosphere at the horizon looks as thin as a contact lens over an eye, and its fragility seems to demand our protection.”

Under certain conditions, Kelly might follow in the footsteps of the late John Glenn, who went from astronaut to politician. Kelly, however, would want to be certain that funding was in place before he committed to an election campaign. His sister-in-law, Gabby Giffords, was a member of Congress, and he saw the fundraising challenges she faced.

“If someone said, ‘We have the infrastructure and the money and want you to run for governor of Texas or for the U.S. Senate,’ I would consider that,” Kelly says.

The Kelly twins returned to their grade-school alma mater in West Orange in May 2016 for a ceremony to change the name of Pleasantdale Elementary to Kelly Elementary School.

Principal Joanne Pollara says Scott Kelly addressed the students “in a way they understood.”

After the visit, the fifth-graders were asked to document their school highlights. “I don’t think there’s one kid that didn’t write down [the Kelly visit],” says Pollara.

Author Wolfe says Kelly’s time in space was “a test of the human body and the psyche.” Being removed from family and friends for so long, Wolfe says, “must be a terrible stress. That’s what he and others in the space station are chosen for, that they could do it.”

Kelly hopes his book inspires people to believe in themselves and in their future. “I hope some young kid reads this book and says, ‘You know, what? I can relate to this guy, and look what he did,’” Kelly says. “Maybe I can do something.”

Daniel Dunaief is a veteran reporter and editor. He lives in Westfield.