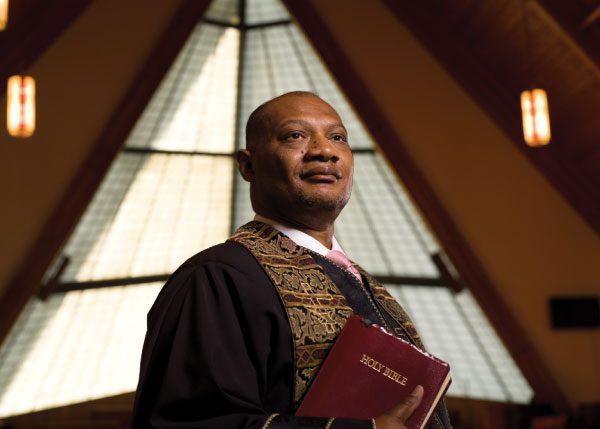

REGINALD T. JACKSON

Minister, Activist

“This is your time,” the Reverend Reginald T. Jackson told 150 congregants at Orange’s St. Matthew African Methodist Episcopal Church on a sunny Sunday in late October—a message that resonated with those filling the pews just nine days before the country would elect Barack Obama as its first black president.

The following day, Jackson was in Trenton, meeting with Governor Jon Corzine to discuss Election Day preparedness for the state’s 500,000 newly registered voters. Two days later, he was off to an education conference in Atlantic City to argue on behalf of school choice.

It was a typical week for the 54-year-old pastor who has never held public office but is considered perhaps the most influential African-American in New Jersey. As executive director of the Black Ministers’ Council of New Jersey, his reach stretches far beyond his base in the Oranges to oversee the direction of more than 600 black churches in the state. By combining his oratorical skills with his role as a conciliator, Jackson has for years placed himself at the center of some of the most divisive issues affecting the black community.

“He’s a man of complete integrity and not influenced by any particular persuasion,” says the Reverend DeForest Soaries, minister of the First Baptist Church of Lincoln Gardens and former New Jersey secretary of state. “He’s supported both Republicans and Democrats. He’ll be critical of both black leaders and non-black leaders. He’s not one Reggie Jackson with the people in power and another Reggie Jackson with people in the community.”

The issue of racial profiling by the state police made Jackson a household name. The long-standing problem boiled into a crisis after three African-Americans were shot by police on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1998. Despite death threats, Jackson directed the charge and kept up the pressure until the police were placed under a federal consent decree and legislation was passed making New Jersey the first state to label racial profiling a crime.

“It just erupted once we started finding out all the cover-up,” Jackson says. “That was a very frustrating time because it seemed [like] all I was doing, 24 hours a day.”

Since then, he’s fought for more funding for the state’s 31 Abbott school districts—although he also supports a school voucher system, a position that has disappointed some urban public school advocates. He also has backed needle-exchange programs for drug addicts and has sought to outlaw banks’ predatory lending practices in inner cities. After a recent hospital stay, Jackson said his next focus will be the shrinking health care available for the state’s underprivileged. Ron DelMauro, CEO of Saint Barnabas Health Care System, says he’d “welcome someone like Reggie Jackson to really stand up and take a look at health care.”

“Reggie is a conscience, a person you can always turn to to get the best advice,” DelMauro says. “He’s a voice for the black community, no question, but I see him as a voice for all the citizens of New Jersey.”

While acknowledging that he’s outspoken, Jackson bristles at the suggestion that he is the state’s most powerful black leader.

“The notion of a person of power is that it is all about you; you’re the man. And I don’t abide by that at all,” he says. “I’m more interested in generating light than heat.”

Jackson first came to understand the influence of the church during his seminary training in Atlanta in the late 1970s, where he met many of the leaders of the civil rights movement. “I saw the impact the clergy could have in improving the lives of people, and that really affected me. I saw how they moved in the political structure and affected policy. It was practical. Not otherworldly.”

After graduating, he was sent to New Jersey, first to a church in Jersey City and two years later to Orange, where he has held the pulpit for the last 28 years. When Jackson took over the Orange AME church it had 100 members and a $50,000 annual budget. Today the church boasts 2,500 members, about 1,500 of whom are active, and a $2 million annual budget. In 2002, the church opened its cavernous new multimillion-dollar structure on the site of the original church.

Though he has steered clear of politics, Jackson did run for one office last year: bishop of the national AME church. The race turned out to be as political as any public office. He ended up withdrawing his name after learning it would mean moving his family—wife Christy and children Regina, 23, and Seth, 3—to Africa for four years. Meanwhile, he found another cause to champion.

“The church is extremely political. It’s become so inward, it’s almost becoming irrelevant to the larger things going on in the world,” Jackson says. “I think the church’s broader mission is outside. There are so many problems that need to be addressed.”

To read about the rest of our power players, click on the links below:

Clement Price and Mary Sue Sweeney Price

If you wish to comment on this article, please comment on the main article page located here.