Ruthi Byrne at Paper Mill Playhouse, one of the numerous nonprofits she serves as a board member. Her longtime friend, Governor Tom Kean, describes Byrne as a “force of nature.” Photo by Peter Murphy

With tons of time during the coronavirus lockdown, Ruthi Byrne has been sorting stuff owned by her husband, Governor Brendan Byrne, who died in January 2018, leaving behind political buttons, pens used to sign legislation, Lenox soap dishes from his 1974 and 1978 inaugurations, ties and tie pins, love letters from law school, a legislative red book from the 1800s and other ephemera. As she touches each item, Byrne mulls its potential destination: the governor’s archives at Rutgers University, the state museum in Trenton, the trash (for those love letters penned by other women, until a grandson intervened). Some items she will give to the Garden State movers and shakers in her orbit.

“If they are interested in politics or the state, I will bring them something,” says Byrne, speaking from the Short Hills home she has owned for 50 years. “If it’s something special that I think will resonate with someone, I’ll give it to them.”

It is fitting that the woman known as just Ruthi—like Cher or Oprah—among New Jersey’s business and political elites is using the isolation of lockdowns to connect with others. An expert at building and maintaining relationships, Byrne’s thoughtful and practiced approach melds her professional and personal identities into one.

“My whole life is one life. I’m friends with my clients. I socialize with my clients,” says Byrne, president of Zinn, Graves & Field, Inc., a public relations and marketing firm.

Byrne was a suburban housewife, as she puts it, when she became active in New Jersey politics in the mid-1970s. She and a handful of volunteers from the League of Women Voters sued Essex County to change its government charter from one that empowered freeholders to a county executive form. The women of Citizens for Charter Change got pushback from the county’s political bosses, who dismissed them with the usual sexist stereotypes. “We were like, ‘Fuck you buddy. We’re not going home and getting pregnant,’” recalls Byrne. “I’m convinced we succeeded because we were women, and we didn’t take no for an answer.”

The successful crusade not only changed Essex County government, but Byrne’s life. During the grassroots battle, she met Brendan Byrne when her group asked the Democratic governor to endorse the effort. He did not, she is quick to add. Instead, support came from then Assemblyman Tom Kean, a Republican, who recalls Byrne’s fearlessness against the power brokers.

“She was willing to go up against the bosses. The payback might be pretty bad, so she impressed me right away that she was willing to take them on. She’s ready to take on anybody,” says Kean, who succeeded Byrne as governor in 1982. “Ruthi’s a force of nature. If you want anything done, it’s better to have her on your side.”

Kean says they have been friends since the charter crusade. In fact, the famous Brendan Byrne–Tom Kean friendship started with Ruthi, not Brendan. Years later, it was Ruthi who realized the potential of pairing the former governors for speaking events. “I was Abbott and he was Costello, and Ruthi managed us,” Kean explains.

[RELATED: Meet Karen Kessler, Master of Celebrity Damage Control]

The Essex County charter battle also launched Byrne’s business. Six of the activists started the firm, which shrank to Ruthi Zinn (her married name at the time), Jeanne Graves and Joan Field; eventually, Graves and Field moved on and Byrne became sole partner, but retained the firm’s name. “I was ready to go back to tennis and cooking,” Byrne says of the firm’s founding in 1978. “My life is completely unplanned. I’ve never planned anything. Never. So we all just sort of went to work.”

The free-spiritedness traces back to her childhood growing up in Brooklyn, the daughter of Sam and Miriam Greenfield, who were teachers before her father became a stockbroker and her mother moved into central administration for the city schools. Everyone called Byrne by her first and middle name, Ruth Ellen, even though her older sister was just Joan. She tried on new names as a child, becoming Tommy one summer at camp because there were too many Ruths in her bunk. (She can’t explain it: “I wasn’t a tomboy, so it was ridiculous.”) It was seventh grade when she decided her given name was “babyish” and declared she’d rather be called Ruthi; everyone complied, except a cousin or two.

Byrne graduated high school at barely 16— her birthday is in March—after skipping kindergarten and completing seventh, eighth and ninth grades in two years as part of a selective program. “I lied about my age, always. I never had a 16th birthday party because I was so much younger that I couldn’t ever admit that I was only 16. I’m dating all these college guys, and if they knew I was 16, 15, 14!” says Byrne, who declined to reveal her current age.

The self-assured teen was a hub of information in high school, but never in a gossipy way, says childhood friend Paula Janis, who would become the guitar-playing star of the 1970s TV show Magic Garden.

“She kept her ears open,” says Janis, who remains a close friend more than 60 years later. “If you wanted to know about anybody, you’d ask Ruthi, and she would know. And nothing has changed. If you want to know anything about anybody in New Jersey, you ask Ruthi.”

The relationships helped Byrne stay well-fed as a kid; on the bus ride to school, she would eat the “huge” lunch her mother had packed, having had a “giant” breakfast, and then ask friends to feed her when the noon bell rang, Janis recalls. Byrne cultivated devotees then, the same way she does now.

“She’s interested. She’ll ask you questions. You don’t feel like you’re talking to a wall, you’re talking to someone who wants to hear what you have to say. That’s why her business is such a success,” Janis says. “People gravitate to her.”

After graduating from the University of Richmond with a psychology degree, Byrne was a research assistant at the advertising firm Young & Rubicam, where her weekly pay was $65, or $52.35 net. She impressed her boss quickly. “He figured out I was pretty smart and I could do his work for him. And I did his work for him.”

She then taught kindergarten and third grade in Brooklyn, until her first pregnancy showed, which back then was verboten. At age 21, Byrne had married Stephen Zinn, a radiologist. They divorced in the early 1980s; Zinn died in 2005. Byrne has two children—Laura Zinn Fromm, a journalist, and Michael Zinn, a finance executive—and five grandsons.

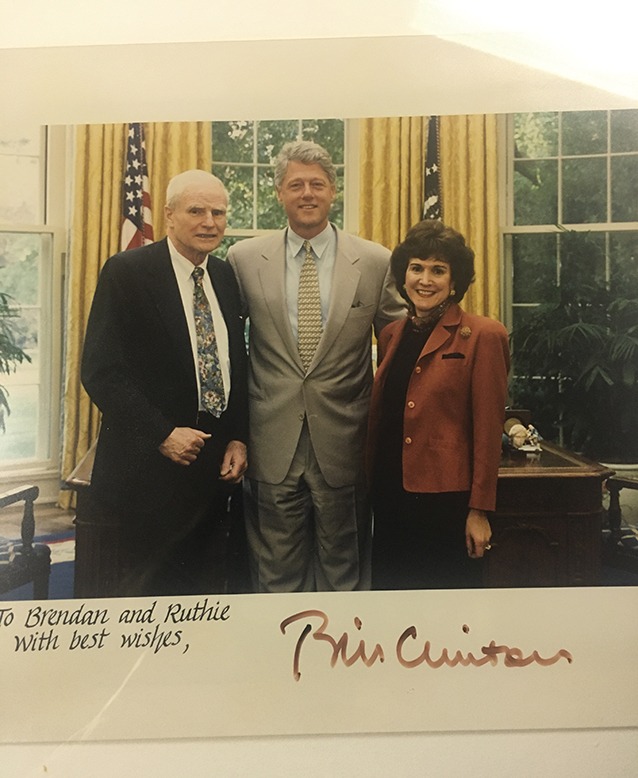

Ruthi and Brendan Byrne enjoy a moment with Bill Clinton in the White House. Courtesy of Ruthi Zinn Byrne

Byrne began dating Brendan years after the Essex County charter fight. They married in 1994 at the restaurant inside the Brendan Byrne Arena. It was a low-key event; the former governor washed his car that morning. “We were determined not to overdo it and not to make a big fuss about it,” she says. They honeymooned in Alaska.

Being the wife of the former governor made an already visible Byrne even more high profile. “Brendan was a magnet, as any public person would be, and he would talk to people,” Byrne says. “You never went anywhere where you were not noticed. Never. People noticed you because they noticed him… If you’re a person who can’t deal with that and you don’t want to be in public life, stay home in the kitchen.”

In business, Byrne is a door opener and has six or seven long-term clients, all big companies, including PSEG, a client since the early 1980s. Byrne’s value to the utility comes from her skills as a networker, her ability to bring people together, and her deep understanding of Garden State people and politics, says Rick Thigpen, PSEG senior VP of corporate citizenship.

“She’s a quiet storm in some ways, a bulldog you’d want to have on your side versus after you, and I mean it in a positive sense. Everyone knows better than to tell Ruthi no,” says Thigpen. “She is not naive in any way, shape or form. She knows the world of politics and is quite familiar with the rough-and-tumble that goes with it. She has been among the movers and shakers of New Jersey for two generations.”

Byrne has remained influential because of her relationships, whether through her business, politics, or her role on 10 nonprofit boards, including Paper Mill Playhouse and Rutgers Business School.

“Most people who are successful in business and politics will say that relationships are everything,” Byrne says. “If you are known as an honest, hard-working, can-do, effective person, you’re going to be all right, because people are going to know your word is your bond. I think you have to be a good listener, and I think you genuinely have to like people and be interested in people. I think that’s the secret sauce.”

The woman who once wore white gloves in the Brooklyn subway is now notorious for dropping the F-word into conversation. But she isn’t letting loose in anger. “I like to say it because I think it lowers the level of formality. I don’t think it should be overused,” Byrne says, noting she gauges people before uttering the expletive. “The sooner you break down the formality, the better off you are and the better off your relationship will be.”

Years before the coronavirus, Byrne became well known for greeting people with an elbow bump instead of a handshake. She started the salutation during a Chamber of Commerce trip to Washington, D.C., concerned about the handshaking among hundreds in close quarters.

“Now, it’s become a thing. People are saying, ‘Ruthi was ahead of her time, she was an early adopter,’ which I certainly am not,” Byrne says during a socially distant lunch at Lithos Estiatorio in Livingston.

It is one more way she is keeping Jersey connected.

Freelance correspondent Sharon Waters wrote about New Jersey couples from opposite sides of the political aisle in the January 2020 issue of New Jersey Monthly.