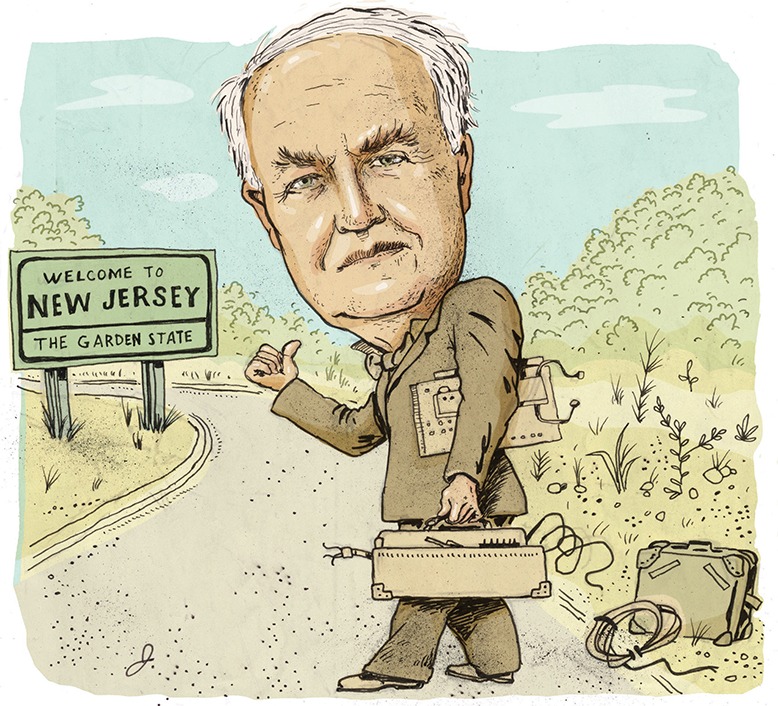

Illustration by John S. Dykes

In the last year or so, by Kathleen Carlucci’s count, people from more than 60 countries and 49 of the 50 states have visited the Thomas Edison Center at Menlo Park, fittingly located in Edison.

“I think South Dakota is the only state missing,” says Carlucci, the center’s director, seated at a picnic table outside the center’s museum. Looming nearby is a 131-foot-tall memorial to Edison, the famed Wizard of Menlo Park.

“Edison changed the world,” adds Carlucci, “right here in Jersey.”

Carlucci and the museum’s staff can expect a spike in visitors this month, with a new Edison biography and movie on the way. Likewise the Thomas Edison National Historic Park in West Orange, which comprises Edison’s lab and his home, Glenmont, in Llewellyn Park.

But how did America’s most famous inventor—born in rural Ohio in 1847—end up doing his most important work in New Jersey?

The story spans the centuries—and the globe. It is a war story and an immigrant story.

Some of this tale is revealed in Edison (Random House), a hefty new biography by Pulitzer Prize–winning historian Edmund Morris, who died in May. Morris tells Edison’s life story backwards, beginning with his death in 1931, at the age of 84, and spiraling back to his birth.

The new movie, The Current War, is sure to attract attention, thanks to its stars, Academy Award nominees Benedict Cumberbatch and Michael Shannon. The movie—shot several years ago, but delayed by production troubles—explores the competition between Edison (Cumberbatch) and fellow scientific pioneer George Westinghouse (Shannon). An early scene depicts a group of Gilded Age venture capitalists traipsing through mud-filled fields in Menlo Park.

Morris tells this part of the Edison story in his new bio.

In 1869, Edison partnered with electrical engineer Franklin Pope, who lived with his mother in Elizabeth, “where Edison, too, would thenceforth be a paying guest,” Morris writes. Edison then “found some laboratory space” in Jersey City and “fell into a commuter’s routine of rising every morning at six to catch the eastbound train…, [proceeded to work] his customary eighteen-hour day, then [wait] in the frigid dark for the one am local to take him back to Elizabeth.”

A few years later, Edison gave his father “carte blanche to find a rural location” isolated enough for focused work, but close enough to New York for meetings. Menlo Park fit the bill.

But that doesn’t explain how Edison got to this neck of the woods in the first place.

Nearly a century and a half earlier, in 1730, 3-year-old John Edeson—the original family spelling—and his widowed mother left the Netherlands and “landed at Elizabeth Town, eight miles south of Newark (then called New Ark),” according to earlier Edison biographer Neil Baldwin. John Edeson raised a large family, but his opposition to the American Revolution forced him to flee to Canada.

Political turmoil upended the family again in 1837, when Thomas Edison’s father, Samuel, was raising his own family in Ontario.

Sam Edison “participated in an antigovernmental revolt,” writes Morris in the new biography, before fleeing “across the border to Michigan, with provincial troops in hot pursuit.” Sam later settled in Milan, Ohio, where Thomas was born and raised. At the age of 19, Thomas set out on his own, first to Louisville, Kentucky, and then to New York City before transplanting to Elizabeth.

Seems like at least one person from South Dakota would want to hear more about this great American story.

RELATED: Edison’s Failure Finds New Life