Someday, schoolteachers will have to rely on taped interviews from Holocaust survivors to educate their students about the atrocities the Nazis committed against the Jewish people and other targeted groups during World War II. For now, many students in New Jersey have the extraordinary opportunity to personally meet survivors, like the seven who shared their stories with New Jersey Monthly.

Since 1994, New Jersey has required Holocaust and genocide studies at every grade level in public schools. Survivors have fanned out across the Garden State over the past three decades to visits classrooms, both in person and, during the pandemic, virtually—bringing an abhorrent history to life with their stories, each one unique, always wrenching. These visits bring something no textbook can give, supplementing the thoughtfully developed lesson plans the New Jersey Commission on Holocaust Education offers to teachers.

The number of Holocaust survivors living around the world today is unknown, but hundreds are estimated to live here in New Jersey, says Helen Kirschbaum, director of the Esther Raab Holocaust Museum & Goodwin Education Center, located inside the Katz Jewish Community Center in Cherry Hill. Kirschbaum works with teachers in the state to arrange survivor talks. She treats survivors with care, knowing their painful memories are stirred up each time they meet with students and often cause nightmares prior to and after each session. At some point during our interviews with the survivors, every one of them broke down in tears recalling what they had been forced to endure.

Yet they are willing to revisit their pain in the hopes of enlightening and educating young people. Survivors share how they managed to rebuild their lives after the Nazi stranglehold brutally snatched away everything that meant anything to them. They also challenge students to speak out against bullies and bigots, to be active participants in making the world a more just place, and to be kind rather than judgmental, compassionate rather than callous.

Now is an especially important time to remember and learn from these survivors, considering the rise in anti-Semitic attacks in the United States and around the world in recent times. This year, April 28 marks Holocaust Remembrance Day, or Yom HaShoah in Hebrew, which honors the 6 million Jews and 5 million others who perished in the Holocaust—and those who survived.

***

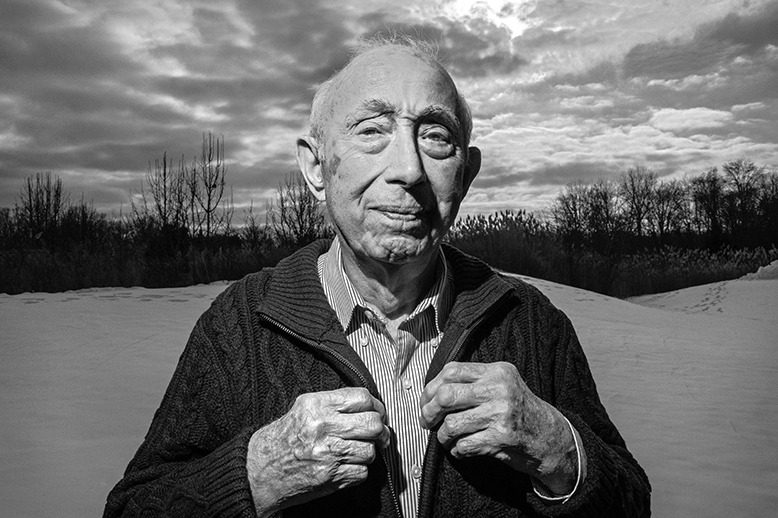

Fred Behrend, 95 · Voorhees

At the age of 95, Fred Behrend sometimes tires more easily than he once did. But that didn’t stop him from presenting a Zoom talk about the Holocaust to Notre Dame High School students in Lawrence Township at 2:15 pm on the same day he completed a four o’clock Zoom interview for this article.

Born in Germany in 1926, Behrend, an only child, was able to stay safe as the Nazis took over by leaving his home in Lüdenscheid to live with another Jewish family about 65 miles away, in Cologne. About 10 years old at the time, he attended a Jewish school there, as Jewish children were no longer allowed to go to public schools.

One day, the Nazis stormed the home where he was boarding, dragging his host parents down the steps and taking them to Poland, where they were killed within days. Behrend and the couple’s two young children remained alone in the house until Quakers working with the Kindertransport—an organization that rescued Jewish children—took the other two children to England.

Behrend’s own father, meanwhile, was arrested in November 1938 on the evening of Kristallnacht—when the Nazis burned and vandalized Jewish businesses, homes and synagogues—and ended up at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. His mother arranged for someone to travel to Cologne to take her son home so they could try to escape together. “There was no question. We had to leave Germany because life there was made impossible for us,” he says. His mother’s brother, having an important post in Denmark, was able to obtain visas and boat passage for them to sail to Cuba.

Behrend’s father was told he could leave the camp if he could prove he’d get out of Germany within two weeks. The visa served as proof. His son was aghast to welcome his father back from the camp as “a skeleton, a wreck of a man.” In Cuba, Behrend celebrated his bar mitzvah, a ceremony held for boys at age 13 in honor of reaching manhood.

About 18 months later, toward the end of 1940, the family made their way to the United States. But things were not easy there for the now teenage Behrend, who experienced “great difficulties” in public school because he “did not command the English language very well.” He graduated “just in time for Uncle Sam to put me into the armed forces” to help in the fight against his native land that had forced him out.

In the United States, Behrend, whose wife, Lisa (formerly Liesl), died in 1991, had two children and became a TV mechanic. One day, he was called to a home to repair a family’s TV set. The woman of the house noticed Behrend’s German dialect and asked where he was from. He told her Lüdenscheid.

The woman seemed stunned. “Many years ago,” she slowly told him, “when I lived with my parents in Cologne, my father brought a young man to board with us so he could go to the Jewish school. He, too, came from Lüdenscheid.” Astonished, Behrend replied with tears in his eyes, “That boy was me.” They hugged and cried together at this unbelievable reunion in their new country.

Behrend, a grandfather of three, has been speaking to students about his experiences during the war for 14 years. “It’s important to teach our young people that hate is not something you’re born with,” he says. “It is something you were taught. Do not follow the teachings of hate but rather the teachings of acceptance and love.”

***

Ryfka Finkelstein, 92 · Cherry Hill

Finkelstein, 92, spent the war alone in her native Poland, running and hiding, with help from kind non-Jews. Photo by Jim Herrington

In her native Poland, Ryfka Finkelstein and her family “lived in danger every minute of every day” when the Nazis took over. It started when she was 14. She’s now 92 and remembers every detail. “My brother and I and our cousin Pearl were caught and arrested [in 1942],” she says. “The police charged us as spies and insisted we were giving Russian partisans food. We were asked where we wanted to die. We were going to die and we hadn’t done anything to anyone.”

Eventually freed, they spent the rest of the war running and hiding. At some point, Finkelstein became separated from her cousin and survived with her brother and the help of kind “righteous gentiles.” Finkelstein never saw her parents again.

“One man started giving me food every evening,” she recalls. “Others would give me a piece of bread. That kept me alive. Anyone helping a Jew in any way could have been killed themselves. Others invited me into their home, but I continued to live outside…Going into anyone’s house could be a trap.” She slept inside any stack of straw she could find and never ventured out in daylight. During those two agonizing years, “I was all alone in the world,” she remembers. Everyone in her family was killed except for her brother. “Today, I am the only one in my family left to talk about the Holocaust,” she says softly.

She arrived in the United States in 1950 and in New Jersey the following year. Her husband, Jacob, also a Holocaust survivor, lost everyone in his family at the Sobibor death camp. Caught trying to escape, he was given three sentences: drowning, hanging, and shooting. Before any of those sentences could be carried out, he attempted another escape and this time was successful.

The Finkelsteins raised three daughters and a son, and have six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. “They make me want to live and be here,” she says, smiling.

Finkelstein speaks to students about her experiences, which is never easy. “It’s very hard for me to speak to students about the Holocaust because we survivors are still hurting,” Finkelstein says. “During these talks, I am a child again. I try very hard not to cry. In my heart I am reliving the horror that we lived through. I have to leave a lot out.” But she promises to keep giving talks. “I vowed that if I survived, I would speak out about what happened. I feel we survivors owe that to new generations. They must be told what humans are capable of doing to others.”

***

Michael Bornstein, 81 · North Caldwell & New York City

When World War II was nearing its conclusion in 1945, Michael Bornstein was just four years old, towheaded with blue eyes—Adolf Hitler’s concept of a boy with perfect physical characteristics. But that didn’t prevent him from being put in a cattle car bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in his home country of Poland. His crime? He was born Jewish.

About 1.5 million children, 1.2 million of them Jewish, were killed by Nazis. Bornstein was one of just 52 children under the age of eight still alive in Auschwitz on January 27, 1945—the day the Soviet Army liberated the camp. Most children had died within two weeks of their arrival there.

As photographed in a now iconic picture taken by a Russian soldier, Bornstein’s paternal grandmother, Dora, carried him out of the camp that day to freedom. During his six months there, Dora, as well as Bornstein’s mother, Sophie, who was later transferred to an Austrian labor camp, saved his life by hiding him in the women’s barracks, mostly under piles of clothing and blankets on beds. “[My mother] told her bunkmates I couldn’t survive any longer in the children’s bunk because I had no protector—some of the older boys were stealing my food—and it was only a matter of time before I would die of starvation,” he says. He continues, “None of the women in my mother’s and grandmother’s barracks argued with my mother about her moving me in with them. There was almost an unspoken rule among the women at Auschwitz—if you see a child, you protect him.”

On liberation day, Bornstein and his grandmother, who were both very ill, happened to be together in an infirmary after Nazi guards forced many others on a death march as the Soviet Army approached.

For 68 years, Bornstein avoided talking with anyone—even his son, three daughters and 12 grandchildren with wife Judy Cohan Bornstein—about his experiences during the Holocaust, including the murders of his father, Israel, and older brother, Samuel, and his maternal grandparents in an Auschwitz gas chamber. So traumatized was he by his past that he preferred to lock it inside in an attempt to lead a normal life.

But in 2014, at 73 years old, he did an about-face when he came upon a Holocaust-denial website showing the photo of him and his grandmother leaving Auschwitz. Bornstein was enraged to realize that deniers were using the photo to say, “See! This child survived!” Since then, he’s been driven to speak out and to tell others his own survival was an extraordinarily rare occurrence.

One of Bornstein’s first acts was to collaborate on a memoir with his daughter Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, an NBC producer. Survivors Club: The True Story of a Very Young Prisoner of Auschwitz (2017) tells Bornstein’s story from his birth in a ghetto in Zarki, Poland, to the camp, to his fulfilling life in America. Here, he earned an undergraduate degree from Fordham University and a PhD in pharmaceutics and analytical chemistry from the University of Iowa, and became a pharmaceutical researcher for major companies, developing treatments for cancer and conditions such as dwarfism. “You can have a wonderful life if you stay strong and look to the future,” Bornstein says.

His book, which became a New York Times bestseller, led to Bornstein and his daughter Debbie being invited to speak to students in New Jersey schools and around the world, spreading their powerful message: “Be kind to others, respect differences, and stand up against injustice of any kind.”

Bornstein says it makes him happy today to see his children and grandchildren “continuing the Jewish traditions the Nazis sought to erase.”

***

Inge Bass, 90 · Marlton

Bass, 90, encountered anti-Semitism upon fleeing to the U.S. in 1938. Photo by Jim Herrington

For years, Inge Bass debated with herself whether she was qualified to speak with students about the Holocaust. “I felt like a fraud,” she explains, “because I was never in the camps. But about four years ago, my son reminded me that we’re losing survivors at a fast rate, and my testimony is needed.”

Bass’s immediate family and a few other relatives were able to escape from Germany just prior to World War II. When the Nuremberg Laws were passed in 1935, she and all German Jews were stripped of their citizenship. Suddenly stateless, they were forced to leave their homeland and restart their lives in other countries—if they could.

In those prewar days, Hitler allowed Jews to leave Germany. Later, he closed off escape routes. “My father and grandfather were in the grain business in a rural part of Germany, where we were one of just three Jewish families,” Bass recalls. “They had to close down their business because it became illegal for anyone to buy anything from Jews. My father, who fought for the kaiser in World War I, was aware of demonstrations against Jews in the bigger cities and realized that we would have to escape.”

To do that, they would need an affidavit from someone willing to sponsor them for five years until they could become citizens, plus a visa for each family member and a low number on a long list of Jews desperate to leave Germany. Bass’s family got visas after her father’s cousin, who lived in the United States, sponsored them. In 1938, when Bass was six years old, the family sailed to New York on the ship Manhattan.

Jews leaving Germany at that time were not allowed to take money with them, but they could take some possessions. Bass tells the story of a furniture maker who created specially designed sofas, each containing a hidden drawer in which people could stash items they wanted to keep secret. Her family stuffed the drawer with expensive Leica cameras and Battenberg lace tablecloths that they planned to sell in America for rent and food money.

“The furniture maker, who wasn’t Jewish, charged for these special sofas, but he was a hero to us because he helped us smuggle out these items that would keep us going for a while,” she says. “We heard later that someone turned him in and he was arrested, taken to a concentration camp, and killed for helping Jews.”

Bass’s new life in America was mostly pleasant—with one exception. “A boy named Dennis who sat behind me in school kept calling me a dirty Jew,” she remembers. “Finally, I’d had enough. I turned around and slapped him on the face. I was almost expelled. After that, I got my seat changed. He was just a nasty kid; you have them everywhere.”

Bass grew up in Bridgeport, Connecticut, where her parents worked in defense jobs during World War II. She moved with her family to New Jersey in 1949 at the age of 18. She and her husband, Felix, married two years later. In 1956, they started their first hobby business in Haddonfield, and in the 1970s, with their son Michael, created what is now the successful Stevens International Hobby Distributors and the AAA Hobbies and Crafts retail store, both of which are in Magnolia. Grandson Alan is now in place as a third-generation owner.

“I’m not a natural speaker,” Bass says, “but I talk to students because I have important lessons to share with them. I tell them that all it takes to turn the tide against evil is for good people to take action.”

***

Charles Middleberg, 92 · Marlton

Middleberg, 92, recalls “dreadful memories” of his family’s fate. Photo by Jim Herrington

Charles Middleberg was born in Warsaw, Poland, but he and his parents, Reuven and Barucha, moved to Paris when he was a toddler. There, Middleberg’s parents welcomed their second son, Victor. Then the Nazis arrived in Paris, and Middleberg’s parents were taken at separate times to Auschwitz, where his mother was killed in a gas chamber.

“I have dreadful memories of what happened to both my mother’s and my father’s families,” he says. “Every one of those people is still in my memory. We had a very large family, but practically the whole family was decimated…The only survivors were my father, one of his cousins, my brother and me.”

Anticipating that Nazis would soon descend on the family’s home, Middleberg’s mother had the foresight to fill a trunk with heirlooms and photos. Following the war, he and his father returned to their old apartment building and retrieved the trunk, which a kind janitor had stored for them. Today, the pictures hang on the walls of Middleberg’s home. “It is my great joy that I still have these treasures from my family’s past, and also my great joy that my children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren will one day have them,” he says.

Around the same time, Middleberg’s mother, fearing for her sons’ safety, sent the boys to a French village 300 miles from Paris, where they stayed at a non-Jewish couple’s home on a tiny farm. Soon after settling in, the boys learned their mother had been caught by the Nazis. As she was taken away, she had begged a woman she knew, a non-Jewish café owner, to take care of her sons. The Middleberg brothers returned to Paris and lived for three-and-a-half years with the café owner and her family. “That woman,” Middleberg says, “took her life in her hands by helping us.”

The brothers, by then 12 and 7 years old, were baptized by a compassionate priest who falsified dates. To save their lives, “we became good little Catholic boys,” Middleberg says. After the war, they resumed their Jewish identities upon reuniting with their father, who had survived a death march from Auschwitz to the Dachau concentration camp before it was liberated by American troops. Their father only weighed 95 pounds, looking like “a skeleton,” Middleberg was horrified to see. “But at least he was alive.”

Charles says he never would have survived without others “risking their lives for us”—a point he always makes during talks with students about the Holocaust.

Charles holds a bachelor’s degree from Temple University’s School of Electrical Engineering and a master’s from LaSalle University. He attended high school and Temple by night, working by day for a moving and storage company. Later, he became an electrical engineer for Philco. His wife, Mathilde, a Holocaust survivor, died 12 years ago. They raised four children.

A few years ago, Charles led three busloads of high school students on a tour of Auschwitz as part of the March of the Living, which brings students to Poland and Israel to learn first-hand about the Holocaust. He can barely get the words out, but tells us, “It was the most painful experience in my life to walk into the gas chamber where my mother was killed.”

***

Fred Kurz, 84 · Cherry Hill

Born in Vienna in 1937, Fred Kurz later relocated with his family to Holland, as his father believed they would be safer from German invasion there. But the Germans invaded Holland in May of 1940.

For two or three years, the family lived in Holland under Nazi rule. Then, the Nazis took Kurz’s father, who later died at Auschwitz. After the Germans arrested Kurz’s mother, Clara, he and his older sister, Doriane (nicknamed Dori), hid in their apartment alone, often behind a wall, until the Dutch underground could rescue them. They were both under the age of eight. For five or six months, the terrified children then hid with non-Jewish families. Holland ultimately lost 90 percent of its Jewish population, including Anne Frank.

Members of the Dutch underground smuggled Kurz and Doris to safety while their mother was sent to the Westerbork transit camp in the Netherlands, and from there to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany. At first, Jewish inmates were considered pawns to be used in trade for German nationals who were rounded up by the British in Palestine. Believing she would soon be released as part of an exchange, Clara Kurz had her children brought to her by the underground so the three could remain together before she was sent to the first exchange location, which ended up being Bergen-Belsen.

When the final exchange didn’t happen, Clara and her children clung to each other at the camp, struggling against starvation, thirst, cold, disease and fear. They were evacuated from Bergen-Belsen as the Allies began overrunning Germany, then spent 14 days on a train, without being given food or water, and were finally liberated by the Soviets. Kurz’s mother developed typhus on the train and died shortly after the liberation of the train. The orphaned siblings were eventually carried by ship to be raised by an aunt and uncle in Brooklyn. Kurz was nine, his sister ten.

There, Kurz started as a fourth grader at a public school, “the first formal schooling I ever received,” he notes. He went on to earn his engineering degree from Columbia University and made a career with RCA and General Electric. Kurz and his wife, Rachel, have three daughters and six grandchildren.

It was his rabbi, Albert Lewis of Temple Beth Sholom in Haddon Heights, who introduced Kurz to the idea of speaking in public about his past. “Dori and I had always felt our memories were too terrible to speak about. But I agreed to do it,” he says. Now, “I recognize my responsibility to talk to students about my memories…even though I don’t relish doing it, because it takes me back to the horrors,” Kurz says. “I prepare for my talk the day before, flashing back to all of the pain that I lived through, but knowing that I must share with future generations what I experienced.”

He emphasizes: “I know that is the only way to prevent hatred and anti-Semitism from spreading unchecked again.”

***

Tova Friedman, 83 · Highland Park

Tova Friedman was six years old when Auschwitz was liberated. She clearly remembers the day. Before the Russian soldiers came, she and a group of children, all girls, were forced to march from their barracks to a gas chamber. Naked, they stood for hours, freezing inside the entrance as cursing Nazi guards surrounded them.

Eventually, the girls were told to dress and return to their quarters. Friedman later learned that they were not killed because of a mistake; the guards had brought the wrong children to the gas chamber. They had been ordered to bring boys, not girls. Friedman escaped death that day. About 150 of her family members did not, dying at the hands of Nazis.

Friedman, born in Poland in 1938, was in Auschwitz with her mother, although they were rarely together, her mother in a women’s barracks, Friedman in a girls’ barracks, except when in an infirmary being treated for diphtheria and scarlet fever.

At the end, chaos ensued when Nazi camp commanders learned the Soviet Army was approaching. Some Nazis escaped, while others ramped up murders and forced a death march with the goal of leaving no witnesses. Friedman’s mother quickly led her by the hand to an infirmary. There, she hid Friedman under the corpse of a woman; the body was still warm. Friedman’s mother hid under a different corpse. They remained there until all was silent. The Nazis were gone. Friedman’s mother helped her daughter climb out. The Soviets had liberated the camp.

Friedman’s father, who had been at the Dachau concentration camp, also survived, and the family began a new life in the United States in 1950 when Friedman was 12. That was after Friedman spent a year in a sanatorium being treated for tuberculosis.

Starting in 1967, Friedman and her husband, Maier, lived in Israel for 10 years, but in 1977 he accepted a job in the United States and they moved to New Jersey. Friedman became a social worker with a master’s from Rutgers, specializing in gerontology. Now retired after two decades as executive director of the Jewish Family Service of Somerset, Hunterdon, and Warren Counties, Friedman continues there twice a week as a social worker. She sees her four children and eight grandchildren as often as possible, grateful all live nearby.

Featured in the 1998 book Surviving Auschwitz: Children of the Shoah by Milton J. Nieuwsma, Friedman is looking forward to the release of her own memoir in the spring, The Daughter of Auschwitz, co-written with PBS writer Malcolm Brabant.

It was in Israel where Friedman gave her first presentation about her life during the Holocaust. Upon moving to New Jersey in 1977, she began speaking in schools, places of worship, and even prisons, where she says inmates have been extremely receptive. “My talks with prisoners focused on bullying and gangs,” she says. “I pointed out to them that Hitler was a gangster. Many of the prisoners I spoke with were gang members and bullies themselves, and I pointed out to them what violence unchecked can lead to.” In schools, she makes presentations to groups of 500–1,000 in auditoriums. She also has 364,000 followers in an unexpected place: TikTok.

Friedman frequently closes her talks by challenging her audience, telling them: “This is not my story anymore. It is now yours to share.”

Barbara Leap entered into a lifelong study of the Holocaust upon learning the depths to which human behavior can sink.