For years, Newark native Paul Auster wondered how his paternal grandfather had died. The famed author knew that his father, Samuel Auster, had spent his early years in Kenosha, Wisconsin. But there were no clues about his grandfather’s death.

Whenever he asked his father to tell him what had happened, he was told a different tale. One time, his father said it was a hunting accident. Another time, he said it was a construction accident. His father had also told him his grandfather was killed as a soldier in World War I.

The younger Auster continued to wrestle with this, asking his cousins if they knew what had happened. They didn’t. They had been fed the same stories about their grandfather’s death. Auster suspected his family was hiding something—and he was correct. But it wasn’t until what Auster describes in his new book, Bloodbath Nation, as “an improbable trick of chance” that he found out what had really happened.

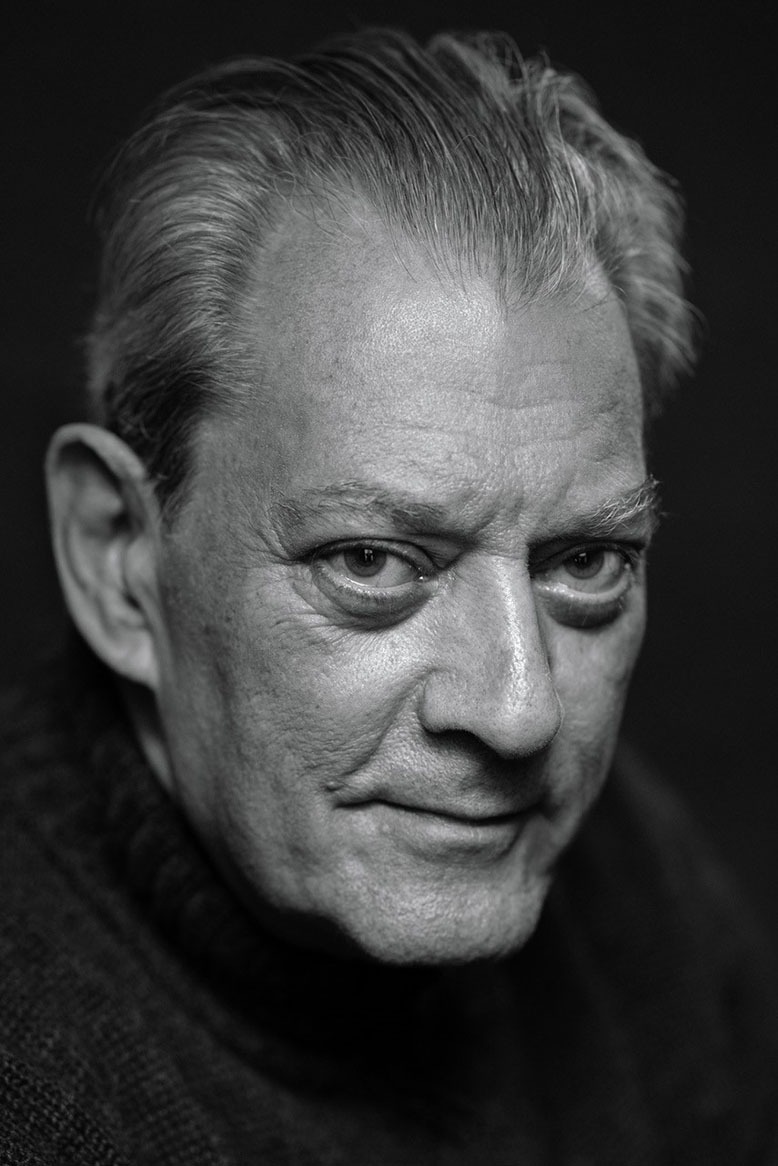

In Bloodbath Nation, author and Newark native Paul Auster examines America’s obsession with guns. Photo courtesy of Spencer Ostrander

The moment that changed everything came in 1970, when Auster was in his 20s. His cousin, traveling abroad, just happened to be seated on a plane next to someone from Kenosha who knew the entire story.

Auster never told his father that he discovered the truth of what had happened on that horrible night in 1919. He never revealed that he knew that his grandmother, estranged from her husband, shot and killed the man she was married to while he was tinkering with a light switch in the kitchen. After the trial—Auster’s grandmother was acquitted on the grounds of temporary insanity—she and her five children left Wisconsin and ended up in Newark, where the children were instructed to never, ever tell anyone what had happened.

But years later, the novelist came to realize how the very gun that had taken his grandfather’s life also ruined his father’s life and turned his uncle—the one who actually had witnessed the murder—into a successful “but haunted man given to savage bursts of rage, horrific jags of shouting, screaming, and uncontrollable anger,” Auster writes.

The revelation that gun violence had impacted his own family, juxtaposed with the country’s gun-violence crisis, forced Auster to think critically about America’s obsession with guns. He also wrestled with his own appreciation of guns. He was a good marksman as a child and says, “I understand the pleasure that shooting guns gives people.”

Then, one summer evening in 2020, before sitting down for a family dinner in Brooklyn, Auster’s son-in-law, photographer Spencer Ostrander, shared his vision for a big project about gun violence in America. Ostrander had been taking photos of places around the country where there had been mass shootings, saying he felt compelled to document these graveyards.

Photographer Spencer Ostrander set out to document “the omnipresence of violence all over the United States” for this project. Photo courtesy of Adam Ferguson

Ostrander is no stranger to loss. In his early 20s, several friends died in one year from drunk driving, overdoses and suicide. He says taking pictures helped him mourn his friends while reminding himself that he was alive. He abandoned plans to attend social work school, instead enrolling in art school. When it came to the mass-shooting sites, Ostrander says, he wanted to take pictures because he didn’t want people to forget what had happened. “My whole goal of the project was to show the omnipresence of violence all over the United States.”

It’s not that hard. Each year, approximately 41,000 Americans are killed by gunshots, according to the Giffords Law Center. Twenty-three thousand of those deaths are suicides. Experts say 400 million firearms are owned in the United States, with firearm sales surging in early 2020. Here in New Jersey, 475 people are killed by guns in an average year, according to the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center.

Experts say the number of people in New Jersey wounded by guns is likely double that.

Auster and Ostrander spent a lot of time together during the pandemic. They belonged to the same Covid pod. The more images Ostrander showed Auster, the more impressed he was with the project, volunteering to write the text to accompany the photos.

Auster says Bloodbath Nation “grew organically out of these photographs.” The photos are bleak. Mostly exterior shots, they include schools, a church and a car wash. There are no people in any of the images, and no guns. The images are both bland and haunting. The photos, says Auster, require the viewer to use their imagination and “try to thrust yourself into the day when the massacre took place.”

A mass shooting occurred in this Tucson parking lot in 2011. Photo courtesy of Spencer Ostrander from Bloodbath Nation

He wanted to broaden the scope of Ostrander’s work and write a text that would also provide a historical look at guns in America.

Ostrander researched mass shootings across the United States. But there were so many, he had to set grim parameters. Twice. First, he selected shootings that took place from the year 2000 to 2020. Then, he set parameters on the number of people shot. At one point, he was looking at shootings involving two or three people. But he couldn’t manage a project of that size, so he set a minimum of four people killed. He studied the cases and mapped out his travels.

Ostrander started the project about a year before the pandemic hit. In some cases, going to these places was logistically difficult. He desperately wanted to avoid re-traumatizing victims. He also wanted to avoid sensationalizing the crimes or inspiring copycats.

There were some sites where he didn’t even get out of the car. One time, in Colorado, he says a state investigator took down his license plate and called him to find out what he was doing.

A Planned Parenthood in Colorado Springs was the site of a 2015 mass shooting. Photo courtesy of Spencer Ostrander from Bloodbath Nation

So when Covid hit, he could travel around the country more freely without drawing attention to himself.

Auster says Bloodbath Nation is a tough read. He says it’s “the most difficult thing I’ve ever done as a writer in all the years I’ve been writing.” But he wanted to create a dialogue about gun violence in America.

Ostrander says he wants people to continue to think about these events even when the news coverage has waned. “I wanted people to look around America and say, ‘This is my car wash, this is my church, this is my synagogue, my temple, my shopping center.’”

Bloodbath Nation explores the deep roots of gun culture in America. The book retells the story of many shootings in America, including the one in 2019 in Jersey City that targeted Jewish people and law enforcement outside a kosher grocery store and at a cemetery.

One thing Auster does not do in this book is name names. For the most part, he has purposely omitted the names of perpetrators out of respect for the survivors and to reduce any type of idolization.

Mass shootings are a tragedy. But they also only represent 1 percent of American gun violence. It’s hard for Americans to wrap their heads around the statistics. But they should, says Michael Anestis, executive director of the New Jersey Gun Violence Research Center. He says Americans need to look more closely at the daily toll of gun violence in their communities, and that it’s time for policy makers to figure out solutions.

New Jersey has some of the strictest gun laws in the United States. The state is ranked eighth for gun-law strength by the organization Everytown for Gun Safety.

In recent news, Governor Murphy signed legislation in December that sets strong minimum standards for who can carry concealed guns in public and clarifies where guns are prohibited in the state—including playgrounds, polling places, train stations, and bars and restaurants that serve alcohol. The move came after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision that lowered the bar for who can carry guns in public.

Ultimately, Bloodbath Nation is a work about the way guns impact American life. Some stories are very private. Others are public. But there’s a common denominator, and that is the gun. In sharing his own family story about his grandparents, Auster asks the reader to consider the sweeping impact of gun violence inside of the American home and at school, the movie theater, houses of worship, the supermarket, the car wash. The list goes on. And on.

Jaime Bedrin teaches journalism at Montclair State University and co-founded the Essex County chapter of Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America.