age fotostock/Alamy Stock Photo

CASINOS

In fall 1976, residents of Atlantic City—a once-great resort that had fallen on hard times—voted in favor of legalized casino gambling. The New Jersey Casino Control Act, passed the following year, raised hopes that legal gambling would pump new life into the local economy. The city’s first casino, Resorts International, opened on May 26, 1978. In time, Atlantic City would boast 12 casinos; major entertainers would light up their stages. Gambling revenue peaked at $5.2 billion in 2006. Unfortunately, competition from casinos in neighboring states took its toll, and by 2014, revenue had tumbled and four of AC’s casinos had closed. Today, several new owners have refreshed the consolidated casino lineup, brightening the outlook for Atlantic City. According to a 2018 report from Stockton University, online gambling and the legalization of sports betting have improved the prospects of the Boardwalk town.—JT

Getty Images

SINATRA

Marty and Dolly Sinatra’s boy, Francis Albert, was an indifferent student. He showed “no real talent for anything,” recalled Arthur Stover, his principal at A.J. Demarest High School in Hoboken. It’s likely Stover never heard Sinatra sing. On September 8, 1935, Frank Sinatra, three months shy of his 20th birthday, made his radio debut with the Hoboken Four on the influential Major Bowes Amateur Hour. A tour followed. Within a few years, Sinatra was singing with Harry James and then Tommy Dorsey, the biggest bandleaders of the day. New Jersey’s first superstar was on his way.—KS

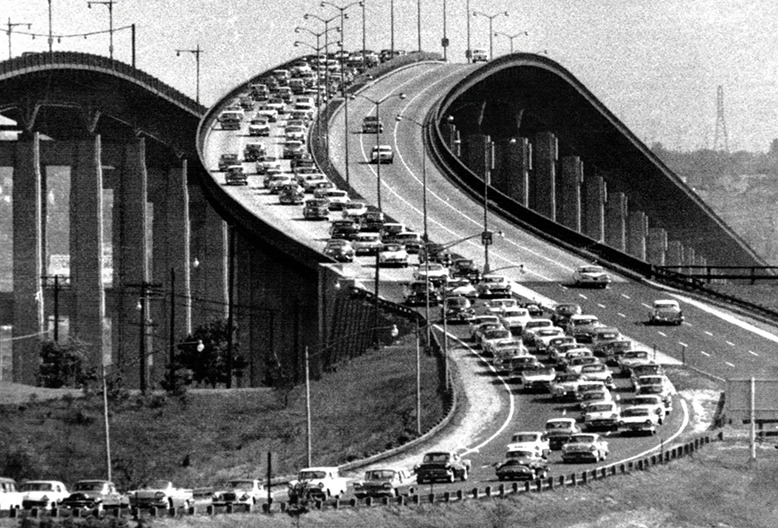

Traffic on the Garden State Parkway, circa 1959.Some 389.4 million vehicles used the parkway in 2018, traveling 6.6 million miles. CSU Archives/Everett Collection

HIGHWAYS

Imagine living in New Jersey before you could ask, “What exit?” That was the case until November 5, 1951, when the New Jersey Turnpike opened to traffic. (A final 9-mile link to the George Washington Bridge was completed in January 1952.) The Turnpike allowed motorists to drive from Bergen County to Salem County without a single traffic light. The 148-mile highway, which would become one of the nation’s busiest toll roads (6.7 million vehicle miles traveled in 2018), served as a catalyst for residential and commercial growth for towns along its route.

Three years later, on October 23, 1954, the official opening of the Garden State Parkway drew raves. “It’s a miracle ride through a surprisingly scenic state,” Travel magazine proclaimed in its September 1955 issue. Designed to blend with the natural environment, the Parkway, which runs 173 miles from the New York state line to Cape May (Exit 0), made it easier and faster for residents of densely packed North Jersey to reach the Jersey Shore (6.6 million vehicle miles traveled in 2018). The two toll roads transformed the state, improving the transportation system and encouraging development and tourism.—TW

Shutterstock

IMMIGRATION

The passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act in 1965 renewed and enlarged the dreams of making it to America. The U.S. immigration system, then quota based, was designed to limit the number of immigrants from African, Asian, and Middle Eastern countries, favoring entry by Western Europeans. The 1965 act’s passage cleared the way for immigrants of all backgrounds to get a fresh start; New Jersey became a prime destination. Only Florida, New York, Texas and California rank higher in total immigrant population, according to the American Immigration Council. Today, immigrants account for more than a quarter of New Jersey’s labor force, and immigrant-owned businesses generate more than $3 billion annually. That figure pushes the state to number 3 in overall economic impact of immigrants, according to WalletHub. It’s been 55 years since the immigration act’s passage, and Jersey still benefits from the diversity delivered.—RT

Winter’s chill transforms the Pinelands National Reserve, 1.1 million acres set aside for recreation and agriculture. Steve Greer

PINELANDS PRESERVATION

Only an act of Congress, championed by Governor Brendan Byrne, spared South Jersey’s sandy woodlands and wetlands from being swept away by construction of the world’s largest jetport, with mega-city to match. Instead, June 28, 1979, America’s first National Reserve set aside 1.1 million Pineland acres for recreation and agriculture, with limits on development. Thus endure miles of sandy trails, soft underfoot; twisty, tea-colored streams perfect for canoeing; to say nothing of the stupendous output of blueberries and cranberries, the state’s top cash crops.

But the protections need protection. The vast underground aquifer, 17.7 trillion gallons of pristine water, is under stress from increased use. Environmentalists and some locals view proposed natural gas pipelines as a threat to waterways and wildlife. One natural gas pipeline was defeated last May, but another is proceeding.

The plight of the Pinelands, as well as their lore and majesty, was first brought to the attention of Byrne—and the nation—in the 1967 bestseller The Pine Barrens, by New Yorker staff writer and lifelong Princetonian John McPhee.—EL

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

DELAWARE CROSSINGS

George Washington and his men crossed the ice-choked Delaware River on Christmas Eve, 1776, in a ragtag fleet of cargo boats and ferries. That trip got a lot easier on January 30, 1806 with the opening of the Trenton Bridge, the first fixed span across the Delaware. In building the bridge, engineer/inventor Theodore Burr, a cousin of Aaron, designed a unique system of five wooden arches suspended from four stone piers. More bridges for carriage and rail travel between New Jersey and Pennsylvania were constructed at various points along the Delaware throughout the 19th century; some doubled as aqueducts to carry water along the river. Many were damaged or destroyed by ice floes, flooding, or upriver bridges that had been swept away.

Today, more than 30 bridges span the river, including interstate highway bridges, railway bridges and pedestrian bridges. Among the most significant is the Benjamin Franklin Bridge, which opened July 1, 1926, to facilitate automobile travel between Camden and Philadelphia. Originally called the Delaware River Bridge, it was for a time, the longest suspension span in the world. Other notable Delaware crossings include the Lower Trenton Bridge, with its iconic “Trenton Makes, the World Takes” lettering; and Dingman’s Ferry Bridge in Sussex County, which dates to 1900 and where the $1 toll is still taken by hand.—TW and KS

BELL LABS

On January 1, 1925, three years after the death of the famed telephone inventor Alexander Graham Bell, the American Telephone & Telegraph Company, which Bell had founded, teamed with the Western Electric Company to launch Bell Telephone Laboratories, a research subsidiary that would thrive in New Jersey. Researchers at the Murray Hill–based laboratory—often referred to as the Idea Factory—were responsible for such technological breakthroughs as the transistor (1947) and the laser (1960). In 1962, Bell Labs partnered with NASA to send the first communications satellite into space. In 2016, Nokia acquired the research hub; it now operates as Nokia Bell Labs.—JT

Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY

The Garden State’s only Ivy League school wasn’t always called Princeton University. And it wasn’t always located in Princeton. The nation’s fourth oldest institution of higher education was founded as the College of New Jersey in Elizabeth in 1746. A year later, it moved to Newark, then to Princeton in 1756. It finally renamed itself in 1896 in honor of its permanent home. A top research university, Princeton has been affiliated with 68 Nobel Prize and 13 Turing Award laureates. Notable alumni include U.S. presidents James Madison and Woodrow Wilson (who also served as president of the university), Michelle Obama, Bill Bradley, Malcolm Forbes and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos.—SV

Courtesy of Johnson & Johnson archives

JOHNSON & JOHNSON

Started in New Brunswick by three brothers—Robert, James and Edward—Johnson & Johnson helped make New Jersey a leader of the pharmaceutical and health care industries. In 1886, the company released its first product, a line of ready-to-use surgical dressings. It was the first. J&J would become the first company to commercially produce first aid kits (1888, initially for railroad workers); maternity kits and baby powder (1894); sanitary napkins (1896); dental floss (1898); adhesive bandages (Band-Aids, 1921); prescription contraceptive gel (1931); aspirin-free pain reliever, (Tylenol, 1959); and disposable contact lenses (Acuvue, 1987). Today, the corporation encompasses more than 250 subsidiaries operating in 60 different countries, with its headquarters still located in New Brunswick.—SV

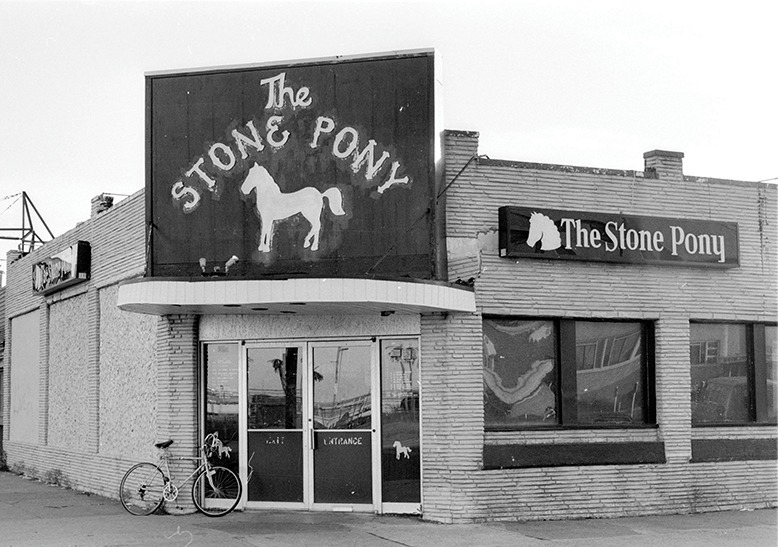

Asbury Park’s beachfront has a sleek new look, but not much has changed at the Stone Pony, where rock bands still rule. Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

THE STONE PONY

It wasn’t the first rock club in Asbury Park. It has few amenities. Yet, thanks largely to the Jersey legends who have graced its stage, the Stone Pony is the most iconic music venue in New Jersey.

Let’s set the record straight: Bruce Springsteen did not get his start at the Stone Pony, which opened on February 8, 1974. Rather, it was Southside Johnny & the Asbury Jukes—fronted by Johnny Lyon, of neighboring Ocean Grove, and featuring Steve Van Zandt—who first filled the club as one of its earliest house bands (billed as the Blackberry Booze Band). On May 30, 1976, Epic Records promoted its signing of Southside & the Jukes with a live radio broadcast of the band from the Stone Pony. The show included guest appearances by Springsteen and other stars—and heaped national attention on the club.

Today, a performance at the Stone Pony is a rite of passage for rising rock acts. As for Springsteen, by the time he first headlined there in September 1974, Columbia Records had already released his first two albums. Still, Springsteen played a key role in the club’s development, often dropping by to perform with Southside or other local bands. “I loved it when Bruce came up,” Southside told The New York Times in 2018. “I could take a break, and he’d do a bunch of singing.”

Through the years, the Stone Pony has survived repeated closings and at least one bankruptcy filing. A thorough renovation in 2000 positioned the club to thrive amid Asbury Park’s revival.—KS

David Grossman/Alamy Stock Photo

HURRICANE SANDY

The superstorm reached our shores on the night of October 29, 2012, making landfall near Brigantine. With wind speeds of 70-80 miles per hour, Hurricane Sandy ripped apart homes, tore up boardwalks and piers, toppled trees, downed power lines, breached seawalls and flooded streets. It was, according to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), “one of the largest Atlantic tropical storms ever recorded.”

Published reports attributed 37 deaths in New Jersey to Sandy. The DEP said the storm damaged more than 300,000 homes. Atlantic City lost 80 feet of its iconic Boardwalk. In some counties, the storm surge reached 9 feet above street level; extreme flooding was reported throughout Ocean and Monmouth counties, and as far north as Hoboken, Moonachie, Little Ferry and Carlstadt.

Facts and figures don’t convey the human element. Just days after the storm, a reporter for New Jersey Monthly recounted the scene as 500 million gallons of water trapped Hobokenites in their apartments. Throughout New Jersey, many were left without power for weeks. At the Shore, homes that had been in families for generations teetered off their foundations or were reduced to splinters. Others were threatened by the destructive mold and debris left in Sandy’s wake.

Sandy changed the face of many beach towns. Taller dunes were built, and homes were raised or reconstructed on stilts. Iconic bungalows were leveled and replaced with larger, modern structures. Years after the storm, New Jersey continues to rebuild.—JT

bilwissedition Ltd./Alamy Stock Photo

HAMILTON

At the height of the American Revolution, George Washington, Alexander Hamilton and the Marquis de Lafayette paused for lunch on July 10, 1778, on a gentle slope next to the Great Falls of the Passaic River in what is now Paterson.

Washington and his trusted officers were no doubt exhausted from the Battle of Monmouth, 12 days earlier. As they picnicked on cold ham, tongue, biscuits and grog, the conversation surely turned to military strategy, but Hamilton’s mind strayed. Gazing at the falls, he is said to have hatched the idea of harnessing the cascade’s effervescent power to create the world’s first planned city of industry and innovation.

Thirteen years later, in 1791, Hamilton, serving as America’s first secretary of the treasury, founded the Society for Establishing Usefull Manufactures, a private corporation chartered to fulfill his vision. In a massive engineering feat, water from the river was diverted into a zigzag canal (or raceway) that would power an aggregation of planned manufacturing mills.

No moment in Hamilton’s eventful, tragically abbreviated life was more important to the future of New Jersey than that picnic on the Passaic.—KS

Photo12/Alamy Stock Photo

THE SOPRANOS

All due respect, but if you haven’t watched The Sopranos, you’re not a true New Jerseyan. On January 10, 1999, HBO viewers met the fictional Mafia family and, oh marone, audiences were hooked. It was the network’s most-watched series until Game of Thrones surpassed it in 2014. Written and directed by David Chase, the six-season show follows Tony Soprano, played by Westwood native James Gandolfini (who died in 2013), a Mob boss who attends therapy. Since the final scene in Holsten’s, a Bloomfield ice cream parlor, fans have begged for more. In a forthcoming prequel movie, The Many Saints of Newark, Gandolfini’s son Michael will portray young Tony. The crime film is due to hit theaters on September 25, 2020.—JK

NEWARK AIRPORT

Newark Metropolitan Airport, which cost $6 million to build, helped set the standard for air travel when it opened on October 1, 1928. Located on 2,100 acres in Newark and Elizabeth, the facility pioneered paved and lighted runways and an aircraft-control tower, all features that other airports would adopt. By 1930, it was the busiest airport in the nation. In 1942, the War Department took over the airport for the duration of World War II. After the war, the rising popularity of air travel led to an expansion and renaming as Newark International Airport in 1973. It became Newark Liberty International Airport in 2002, following the 9/11 terrorist attacks. The airport continues to evolve. Currently, a replacement for Terminal A is under construction; a Terminal B replacement and a new monorail will follow.—TW

A westbound traveler crosses from New York to New Jersey shortly after the December 22, 1937, opening of the Lincoln Tunnel. Bettmann/Getty Images

BRIDGES & TUNNELS

During the 19th century, residents of northern New Jersey might have gazed across the Hudson River at booming Manhattan and felt that they were the ones living on an island. Ferries were the only direct means from Jersey to Manhattan. The earliest railroad tunnels debuted in the first decade of the 20th century, but it wasn’t until the opening of the Holland Tunnel on November 13, 1927, that motorists could drive from New Jersey into Gotham. Named for its chief engineer, Clifford Holland, the tunnel was constructed between 1920 and 1927 at a cost of $48 million. The initial toll: 50 cents. Just over 15 million vehicles used the tunnel in 2018.

Four years later, on October 25, 1931, the first cars crossed the George Washington Bridge, a 4,760-foot span connecting Fort Lee to northern Manhattan. Construction of the bridge took four years. A lower deck—nicknamed “the Martha,” after George’s wife—opened in 1962. The two-deck span is the nation’s most heavily traveled bridge, with just over 51.5 million vehicle crossings in 2018.

The Lincoln Tunnel into midtown Manhattan was built in three phases starting in 1934. The first tube opened on December 22, 1937. The north and south tubes followed in 1945 and 1957, respectively. Just under 19 million vehicles used the tunnel in 2018.

The peak-hour E-Z Pass toll for all three Hudson crossings is now $12.50.—TW

Alfred Eisenstaedt/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images

FULL-SERVE GASOLINE

You’ve seen the bumper stickers proudly displayed: New Jerseyans don’t pump their own gas. But why not? The self-service ban began in 1949, when the state Legislature passed the Retail Gasoline Dispensing Safety Act, citing driver safety and convenience. The law’s lesser-known origin story, according to Star-Ledger columnist Paul Mulshine: Hackensack gas station owner Irving Reingold lowered prices for customers willing to fill their cars themselves; furious competitors retaliated by persuading the state to outlaw the practice. In the decades since, lawmakers and others have repeatedly challenged the ban, only to be met by strong public pushback. Polls show continuing consumer support for leaving the law alone. Many locals revere it as an iconic benefit of Jersey living. Full service, at least for the foreseeable future, seems sure to stick around.—JF

CHERRY HILL MALL

Upon opening its doors October 11, 1961, the Cherry Hill Mall became the first enclosed shopping center on the East Coast. It led the region by creating an air-conditioned, 1.3 million-square-foot, dual-winged megaplex. The mall offered an experience beyond retail that included fountains, a pond, tropical plants and an aviary with exotic birds. Malls, though seldom this extravagant, have battered downtown shopping areas for decades. Today, many malls are shuttering, but the Cherry Hill Mall continues to thrive, with 130 stores and plenty of eateries. The birds, however, have flown.—DC

PATCO

Debuting on February 15, 1969, the PATCO Hi-Speedline provided a rapid rail link for Camden County commuters to downtown Philadelphia. Nearly 38,000 riders now use the train each weekday; 10.5 million rode the line in 2018. Ground was broken in 1964 for the 14.2-mile line, which has nine stations in South Jersey and four in Philadelphia. PATCO’s automated trains can run with a single operator and reach speeds up to 75 mph.—TW

Bettmann/Getty Images

PATERSON SILK STRIKE

It began on February 25, 1913. Some 25,000 protesters organized in Paterson, shutting down the city’s silk business for five months. The Paterson mills, desperate to keep up in the competitive silk industry, had been increasing workloads and reducing wages. Many in the largely immigrant labor force struggled through 55-hour weeks, with children by their sides. Finally, they had had enough. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) united silk weavers of all backgrounds in an effort to cut their exhausting shifts to eight-hour days.

The strike lasted until July; nearly 1,850 strikers were arrested, including IWW leaders Elizabeth Flynn and William “Big Bill” Haywood. Those out of work took odd jobs to survive, many sending their children to stay with family. Local bakeries donated leftovers to the cause.

Ultimately, the strike failed to produce the changes sought. However, it is widely viewed as an integral step in the 20th-century movement to improve workplace conditions.—RT

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

EDISON

“I am experimenting on an instrument which does for the Eye what the phonograph does for the Ear,” Thomas Edison wrote in 1888. The inventor’s experiments led to the launch on February 1, 1893 of the Black Maria, the nation’s first film-production studio. Named for its resemblance to a police wagon, the studio in West Orange was the site of such short films as Fred Ott’s Sneeze, the first movie copyrighted in the United States, and Prof. Welton’s Boxing Cats.

Edison’s work set the stage for New Jersey to be the early center of moviemaking. Fort Lee hosted more than a dozen film companies in the early 20th century as filmmakers took advantage of the state’s scenery and cheap real estate—all before they decamped to Hollywood.

As for Edison, his more than 1,000 patented inventions (most developed at his labs in Menlo Park and West Orange) included the stock ticker, the phonograph and the light bulb.—TW

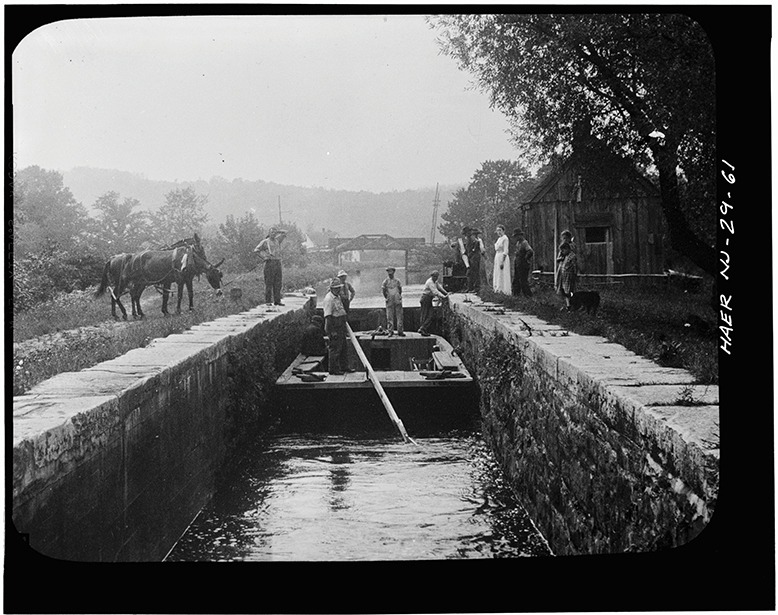

Morris Canal boatmen guide a barge through a lock in Phillipsburg. Barges carried coal and other cargo across the state. Alpha Stock/Alamy Stock Photo

MORRIS CANAL

The Interstate 80 of its day, the Morris Canal cut a meandering, 102-mile path across northern Jersey. New York’s Erie Canal was nearing completion when the plan for the Morris was approved in Morristown in 1822. The initial stretch, between the Delaware River at Phillipsburg and Newark, opened November 4, 1831, with an extension to Jersey City and the Hudson River completed in 1836.

A team of two mules on the towpath could pull a barge carrying 25 tons of coal or other cargo across the state in about five days, according to historian James Lee. Barge capacity eventually exceeded 70 tons, and it was not a flat ride. Through a system of locks and mechanical inclined planes, the barges traversed elevation changes of more than 900 feet.

The heyday was brief. By the early 20th century, railroads had rendered the Morris obsolete. Today, the terminal basin at Liberty State Park in Jersey City is the site of luxury high rises, a private marina, and two upscale restaurants, Liberty House and Maritime Parc.—EL

Empty Sky in Liberty State Park is one of some 150 memorials around the state dedicated to the memory of those who died on September 11. Wunder Images/Alamy Stock Photo

SEPTEMBER 11

No, no one was cheering in Jersey City as the towers fell on September 11, 2001. Everywhere, the crumbling roar was followed by a terrible hush. In New Jersey’s commuter parking lots that evening, unclaimed cars mutely testified to the toll. In all, an estimated 750 Jerseyans perished, the second highest toll of any state, after New York. Middletown alone lost 37, the most per capita of any municipality in the state.

Dazed, we dutifully popped open our trunks at the river crossings and adjusted to bomb-sniffing dogs and long-handled mirrors inspecting the underside of our cars. “See something say something,” said the signs, but it was unclear what constituted something—apart from an unattended backpack, which could, and still will, clear a public area in an instant.

The acute phase passed, but the days when you could simply walk to your airport gate, unscreened, bottle of water in hand, almost seem a fairy tale. On the 10th anniversary of the attacks, New Jersey dedicated its official 9/11 memorial, Empty Sky, at the tip of Liberty State Park. Two long, thin slabs, placed side by side on edge, mirroring the proportions of the towers, enclose visitors and point them solemnly toward Ground Zero.—EL

Bob Peterson/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images

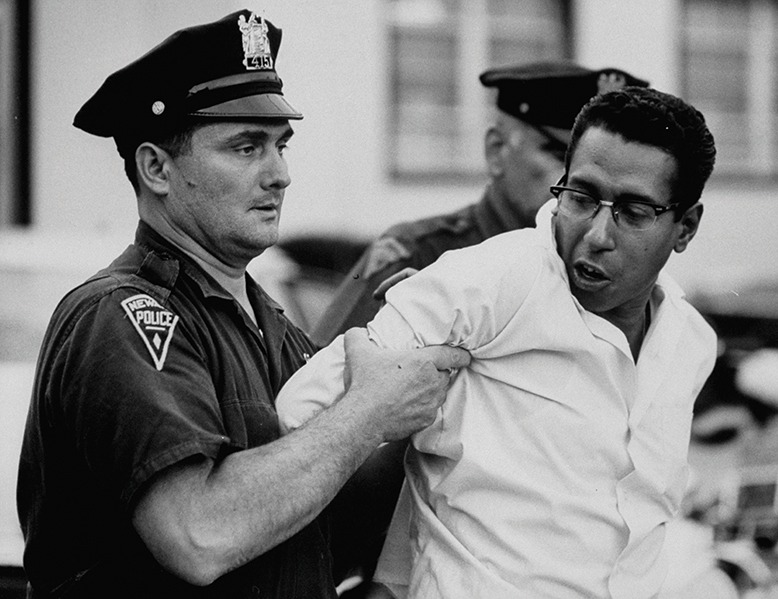

NEWARK RIOTS

The summertime uprising left the once-thriving neighborhoods and downtown of New Jersey’s most populated city devastated for decades. For five days, starting July 12, 1967, violence and looting beset Newark. An incident of police brutality sparked the flames in the midst of smoldering frustrations about housing discrimination, unemployment, and the failure of the city’s leadership to reflect the predominantly African-American community. In the end, the governor sent in the National Guard to quell the disturbance, which left 26 people dead, many injured, and the city’s businesses and residential areas forever changed. Government and leadership changes followed the riots, but more than 50 years later, Newark still bears scars as it attempts to revitalize, street by street.—DC

GLASSMAKING

German Quaker Caspar Wistar founded the nation’s first successful glass factory in 1739 in Alloway. South Jersey’s sand and waterways were ideal for glassmaking. Wistar, a neighbor of Benjamin Franklin, produced windowpanes, bottles and glassware for Franklin’s electrical inventions. During enforcement of the Townshend Acts in 1768, governors were asked by the British government to report on manufactures in the colonies. Then governor of New Jersey William Franklin, Ben’s son, downplayed the success of the factory. The Salem County Glass House, he wrote, “makes a very coarse Green Glass for Windows, used only in some houses of the poorest Sort of People. The Profits by this Work have not hitherto been sufficient it seems to induce any Persons to set up more of the like kind in this Colony.” After the Revolutionary War, Wistar’s business was sold, but the glass industry in South Jersey continued to thrive. Today, WheatonArts and Cultural Center in Millville houses interactive artist studios, gift shops and the Museum of American Glass. Some of the 22,000 pieces in the museum date to the 1700s.—JK

Doreen Spooner/Keystone Features/Getty Images

EINSTEIN

Albert Einstein first visited Princeton University in May 1921 to deliver a series of lectures (in his native German) on his then controversial theory of relativity. He also accepted an honorary doctor of science degree from Princeton during the visit. The Princeton University Press published an English-language transcript of the lectures, The Meaning of Relativity, the first book by Einstein available from an American publisher. The book has been translated into more than 50 languages.

It wasn’t until 1933—when Adolf Hitler came to power while Einstein was visiting the United States—that the wild-haired theoretical physicist would finally return to Princeton as a permanent resident. He accepted an appointment at the newly founded Institute for Advanced Study, where he was an integral part of Princeton’s intellectual community for the following 22 years, until his death in 1955.—SV

Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images

THE BOARDWALK

The Atlantic City Boardwalk opened on June 26, 1870, with a simple goal: Keep sand out of hotel lobbies. The original 8-foot-wide, mile-long walk was raised just 1 foot off the sand. It was dismantled at season’s end.

By the 1890s, the Boardwalk, now a permanent structure, became the center of commercial activity. Over the following decades, hotels (the Shelburne, Marlborough-Blenheim), entertainment centers (Garden Pier, Steel Pier) and an arena (Convention Hall, now Jim Whelan Boardwalk Hall) attracted visitors from around the nation. The Miss America pageant, which began in 1921 as the Inter-City Beauty Contest, widened the city’s appeal and extended the summer season. Entertainers from Harry Houdini to Louis Armstrong thrilled crowds at Boardwalk venues.

World War II transformed Atlantic City into a military training base. Hotels housed troops, Haddon Hall (now Resorts Casino Hotel) served as a hospital, and soldiers trained for overseas duty in Convention Hall and on the beach. AC became a resort again after the war, but urban decay, air travel and interstate highways chipped away at the city’s appeal. The introduction of legalized casino gambling in 1978 breathed new life into the Boardwalk, a constant in a changing city.—TW

EMANCIPATION

Slavery was abolished in New Jersey in 1804, but that was the merest baby step toward full freedom. Female children born to slave mothers after July 4, 1804 remained in bondage until they reached the age of 21, males until 25. The Gradual Abolition Act “was designed to placate slave owners,” says Maxine Lurie, history professor at Seton Hall University. It didn’t go exactly as planned. After the act took effect, Lurie says, “it was hindered when slaves were transported south rather than being able to reach the age for freedom.” As for adult slaves and children born before 1804, some remained enslaved until the state passed a further abolition bill in 1846. Even then, freed slaves could be apprenticed for life to their owners. Slavery would not be completely eradicated in New Jersey until 1865, when the U.S. Congress passed the 13th Amendment.—DD

DESEGREGATION

New Jersey’s modern Constitution—completed September 10, 1947, by a convention of delegates—strengthened the office of the governor, established equal-rights protections for women, and revamped the state’s court system. But perhaps most significantly, the Constitution—New Jersey’s third such document—codified the desegregation of schools seven years before a landmark Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education, outlawed school segregation nationwide. New Jersey remains the only state that codifies a ban on school segregation.

The change followed a 1944 lawsuit—Hedgepeth and Williams v. Board of Education—wherein the State Supreme Court ruled that two black children, Leon Williams and Janet Hedgepeth, could not be barred from attending the whites-only middle school in their Trenton neighborhood. Further rulings followed, including Booker v. Board of Education in 1965, which erased the distinction between de jure and de facto segregation, and outlawed both.

The Constitution’s ramifications were on display in 1971, when the State Supreme Court blocked Morris Township’s efforts to establish its own high school independent of Morristown, the municipality it surrounds. In essence, the affluent, largely white suburb of Morris Township could not legally separate its school system from Morristown, a lower-income community with a growing black population.

Despite the legal precedents, problems remain. Housing disparities have made New Jersey the nation’s sixth and seventh most segregated state for black and Latino students, respectively.

Meanwhile, in 1991, the Trenton school that once banned non-whites was renamed Hegepeth-Williams Middle School.—RT

Tears mix with beer as federal agents destroy bootleg suds seized during a Prohibition-era raid in Hoboken. NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

PROHIBITION

When the 18th Amendment took effect on January 17, 1920, proponents of Prohibition—known as “drys”—looked forward to an era of reduced crime and empty prisons. Boy, were they wrong. Prohibition turned ordinary—but thirsty—citizens into lawbreakers and promoted corruption and organized crime. In New Jersey, Atlantic City became a prime importation center for illegal booze and a breeding ground for Mob activity. Jersey crime bosses like Gaspare D’Amico, Stefano Badami and Longie Zwillman held sway over bootlegging, along with the Jersey factions of several notorious New York and Philadelphia crime families.

Prohibition was repealed in 1933, but the damage had been done. The organized crime elements that prospered during Prohibition would for decades control criminal activities in New Jersey, including labor racketeering, loan sharking, money laundering, the drug trade and illegal gambling.—KS