Hetal Vasavada. Photo courtesy of Madelene Farin

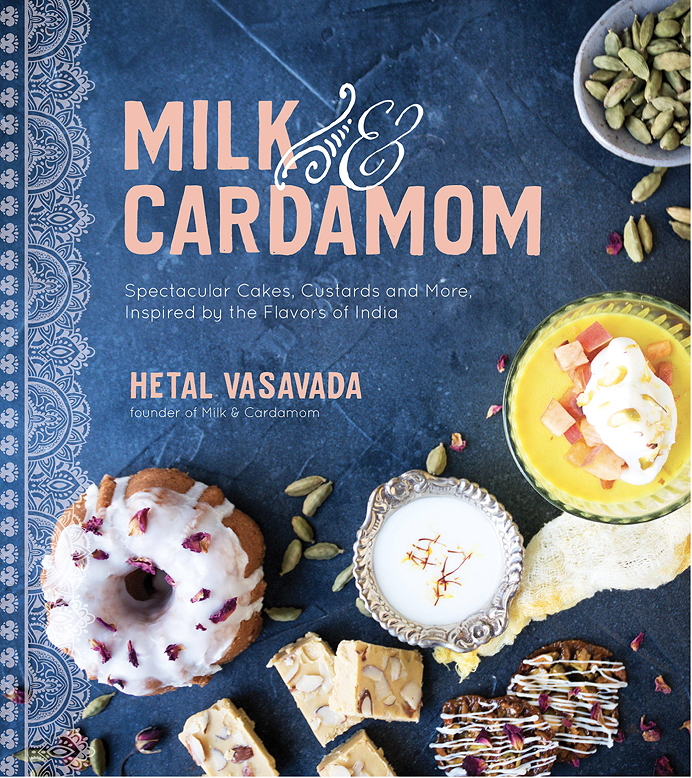

To say Hetal Vasavada is ambitious is to put it lightly: not only did the baker and Bloomfield native just publish her first cookbook about Indian sweets, Milk and Cardamom, she wrote about a category that she was originally told was “too niche.”

Vasavada knew what she was up against. “Indian desserts in general—most non-Indians haven’t heard of half of them,” she says. But Vasavada isn’t afraid of a challenge. Years before the cookbook, Vasavada’s baking skills earned her spot on season six of “MasterChef” on Fox, making it close to the end of the competition. With that chaos—and Gordon Ramsay’s braying—now behind her, Vasavada is busy promoting her budding brand, including a cookbook that straddles cultural divides with delicious, creative recipes (cardamom-chickpea flour fudge called magaz, rhubarb-rose compote, coconut cream, etc.) without compromising her own trailblazing culinary perspective.

Table Hopping: Your mother comes up in the cookbook. Is that how you first learned to cook?

Hetal Vasavada: My mom pretty much taught me. My family in Bloomfield immigrated from India. All my cousins used to live with us or come visit, so we’d always be cooking together. And one of the things the women do is prep all the food for dinner. For me, it started from there.

TH: How did you begin to bake?

HV: I had never really baked—that’s not an Indian thing. It’s not something my mom would have done for me. I would watch the Duncan Hines commercials and wish I could bake. When I went to college [for biochemistry], I started baking out of the dorm using mixes. My lab professor said, “If you can bake from scratch, you’ll be able to pass your labs!” And I realized I really enjoyed it. It’s a very zen thing to do. Everything has a purpose, every ingredient has a reason, there’s a method to every technique. And I like the fact that I can control the outcome. I’m a very Type A personality!

TH: How did you go from hobby to a branded site like Milk and Cardamom?

HV: I started a blog for myself in 2010, almost 10 years ago. I never expected anyone to go to the site and cook off it! It was for me to remember the recipes my mom gave me. Then I started writing the Milk and Cardamom cookbook four years ago, creating recipes for other people to create.

TH: Was a cookbook always part of the plan?

TH: Was a cookbook always part of the plan?

HV: Right after I got off “MasterChef,” I wanted to do a cookbook so bad! But my contract prevented me because it would compete with that season winner’s cookbook. I had to wait three years until my contract ran out. But that gave me time to test recipes and ideas, narrow down my concept and get a gauge on whether there is a market for this. Once Season came out from Nik Sharma, and seeing the response to his book, and seeing the response to Indian-ish by Priya Krishna, I realized: “There’s a space for my book.” And I’m happy there is.

TH: How would you characterize that space? In your introduction you talk about some recipes being “Not 100 percent American and not fully Indian.” Is that a difficult point of view to sell—or exist in?

HV: When I would go visit India, I wasn’t Indian enough. In the U.S., I was too Indian, not American enough. The same theme played over on “MasterChef.” I’d make a dish, the Indian community would say that’s not authentic, and all non-Indian people would say “All she can do is Indian, she can’t be MasterChef.” Only in the last two years is it being embraced to be [this space] itself. Like, it’s okay if you like cakes and cookies over Indian desserts, that’s fine, that doesn’t make you any less Indian, and it doesn’t make you any more American. There’s a whole new cooking genre now from first generation people. The kids of ‘70s and ‘80s immigration are coming out with these evolved American-fusion recipes.

TH: What about dealing with Indian cuisine as “exotic,” or simply the pressure to represent it as a whole?

HV: I’m not a fan of the word exotic. It makes me feel “other.” “You’re exotic, you’re different, but it’s okay!” It’s got a weird false-positive connotation. And there can be a lot of pressure to represent “Indian food.” For a long time, everyone just assumed chicken tikka masala was all over India.

TH: In that vein, does it frustrate you when things like turmeric, for instance, become a trendy “discovery” in food crazes like “golden milk”?

HV: It can be a little frustrating. These are the same things I got made fun of for as a little kid. But at the same time, it’s exciting to see people are embracing it. I would suggest that if people are going to embrace ingredients from pantries around the world, to make sure they’re buying ingredients that aid that location. I only source my turmeric from from Diaspora Co. She sources from Indian farmers who get healthcare and get paid quadruple the regular rate. Just to be conscious of where you’re sourcing the spices from—it’s important. As important as trying it!

TH: Speaking of trying new flavors, how can I outfit my very average pantry to be ready for your book?

HV: We live in an age where ingredients are so accessible. There’s Amazon; you also see more Indian stores. Even in your regular grocery store, they have an aisle with Indian ingredients in it. I wanted to go at it like, “This is just a normal ingredient for us, and it can be a normal pantry item for you in your kitchen.” I do give a little explanation behind ingredients like cardamom or jaggery, but I wanted it to be very easy. If you look at the recipes, there are very few ingredients. I kept it very simple. It’s a way to invite people in and say “Look, it’s only a handful of ingredients. Just order on Amazon and go for it!”

TH: What’s something non-Indians may not know about Indian desserts?

HV: The biggest is probably that when anything happens in anyone’s life—a graduation, a baby shower, your cricket team wins—it’s customary to send boxes of barfi and mithai, Indian sweets. Sweets are eaten in celebration. In fact, the first thing you do as a married couple is eat jaggery or some sort of sweet to recognize that sweet moment in your life. There’s a lot of symbolism when it comes to desserts in Indian culture.

TH: You were told your book was too niche at first, now you’re on a book tour. What’s the response like so far?

HV: The overwhelming response from a lot of first generation Indian-Americans is, “These are the flavors of my childhood,” and “I can relate so much to the stories in your book, waiting at Patel Brothers Indian grocery, being annoyed and eating kulfi!” Those memories, thousands of people have the same exact associations—but also wanting cake, wanting brownies! And I’m actually getting a lot of chefs and bakers that have never heard of these things who are so excited to hear of something new. You can see the excitement in their eyes.

TH: Since you’re Type A, I have to ask—what’s next?

HV: Hopefully book number two! I’d like to do a regional cookbook, a savory regional cookbook on Gujarati cuisine, where my parents are from.

Info on Hetal Vasavada’s book tour can be found here. (On July 28, she’ll be back in her home state, teaching kids to make Ladoo at a Mommy & Me Cooking Class from 11am to 1pm at the Presence Atelier in Orange.) You can purchase the book here, and keep up with Hetal’s baking—and cooking—on the Milk and Cardamom Instagram.